To this day, historians argue about what the phenomenon of the student generation of 1968 actually involves. Perhaps the most fitting explanation is that the year represents a historic turning point, a culmination of developments that had been gradually emerging prior to it. Traditions, institutions, power structures and social realities were scrutinized with a previously unseen urgency. This also applies to the sphere of art.

Although art has of course always been political and has had a political impact in one way or another, the year 1968 saw a radical turning point. Henceforth, so the belief, art would no longer represent and affirm the powers that be, but rather criticize and ask uncomfortable questions. This turning point went hand in hand with a profound revolutionization and democratization of the art system. On the one hand, the range of opportunities for artistic expression expanded vastly, while on the other countless new, alternative forms of presentation and distribution for art arose.

The balance between art and life, art and politics became an almost insurmountable challenge

People often attribute artists with a particular sensitivity for their environment. When observing their works in the isolation of the “white cube” that is the museum, however, it’s often easy to forget that they are not ‘just’ artists, but also human beings who are definitely part of the society in which they live. The balance between art and life, art and politics thus became an almost insurmountable challenge with the developments of 1968.

GAAG, Blood Bath, 1969, Image via: inenart.eu

Two simple examples may clarify the dilemma: Anyone who was politically active, for example by demonstrating on the streets against the Vietnam War as many young artists of the classes of ’68 did both in the USA and elsewhere, was not able to work in the studio at the same time or vice versa. In addition, it remained vital for artists to create, to show and to sell art. Yet museums and galleries were considered places for the social elite who opposed the desire for radical democratization and decentralization.

Tired of climbing between the ivory tower and the street

One contemporary witness, art historian Lucy Lippard, summarily concludes that artists grew tired of climbing between the ivory tower and the street. So what could they do? Radical Marxist groups, including members of the Fluxus movement or the Situationists surrounding Guy Debord, simply called for the abolition of (high) art and the art system. Those artists, however, who wanted to be politically active but didn’t aim to eliminate such a system therefore had to rethink the relationship between art and politics once again. The result was a tense interplay of artistic strategies and political-activist approach. In this context, countless new forms of organization and expression emerged. Many of these – albeit in a changed form – are being reflected in turn as an integral part of political and activist contemporary art.

During the time in which the private became political, action art and happenings flourished. This is hardly surprising, since these new art forms that declared the body to be a material for art offered a way of addressing social and political themes with a new directness. Allan Kaprow, known as the “inventor of happenings”, called this the “ultimate form of a democratic art”. At the same time, it was his overriding didactic goal to enable participants to have physical experiences that would prompt them to communicate and transform them into emancipated individuals. Along intricately planned trails, they were able to undergo entirely different aesthetic experiences.

Hijacking the sculpture garden of the MoMA

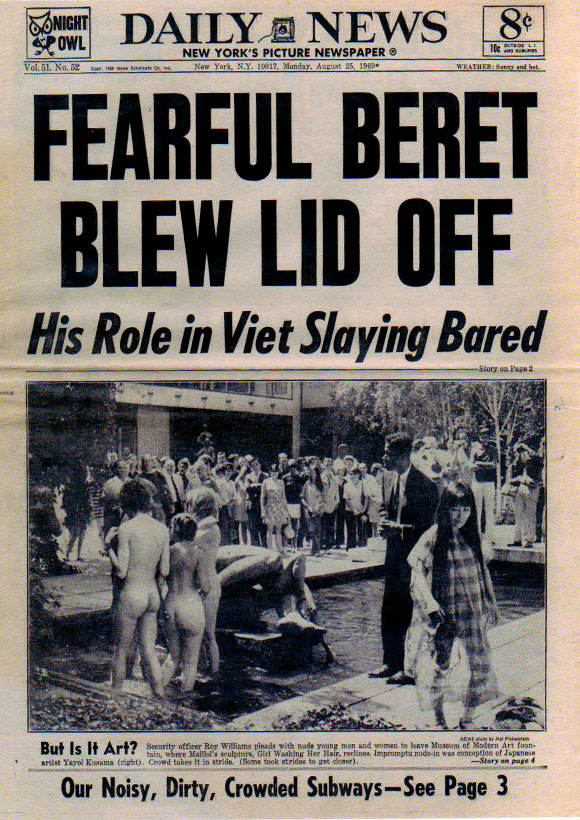

Artist Wolf Vostell gave the concept added political spice by enriching the installations he created with politically critical themes, prompting participants to address topics such as the Holocaust or the Vietnam War, for example. Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama gave the concept a different spin with an interesting interpretation of Action Art and hippy event in 1969. She had a group of performers hijack the sculpture garden of the MoMA in New York. They shed their clothes and waded around in one of the big water basins in the garden, where they posed with a bronze sculpture until they were eventually thrown out of the museum by an attendant.

Front page of the Daily News with a photograph of Kusama’s “Grand Orgy to Awaken the Dead” at MoMA, August 25, 1969, Image via: moma.org

Numerous photographs ensured that the action achieved a huge amount of media coverage. Kusama, for her part, knew how to use this skillfully to disseminate her provocative manifesto on the “Mausoleum of Modern Art”. In it, she complained that the MoMA neglected living artists, valuing only dead artists instead. She argued that it was a showcase for vanities and double morals, in which you can take off your clothes in the best of company (by which she meant, of course, the countless naked presentations in the museum collection). Her counter-proposal was very much ‘in tune’ with the times: The museum should be a place for love. In fact, the idea of the happening was quickly picked up on by the hippy movement, which soon labeled any form of spontaneous gathering in the name of love and peace a “happening”.

The „Mausoleum of Modern Art“ neglected living artists, valuing only dead artists instead

Just a few months after Yayoi Kusama’s action, the MoMA once again became a showcase for a quasi-spontaneous art action. Jean Toche and Jon Hendricks, members of the so-called Guerilla Art Action Group, or GAAG for short, paid the museum a visit. They went into the exhibition rooms and took a painting by Kasimir Malevich off the wall, replacing it with a manifesto. In it, they demanded the sale of paintings worth one million dollars and the distribution of the money to those in need, as well as the communalization of the museum structures. They declared the entire action to be an artwork, thus ensuring they wouldn’t face legal consequences for their act of sabotage. Their gambit worked and the museum even engaged in dialog with the artists.

Yayoi Kusama with sculptures in her New York studio, 1963–4. © 2012 Yayoi Kusama. Courtesy Yayoi Kusama Studio Inc., Image via: moma.org

In another action, the group spilled cow’s blood all over the foyer of the museum and disseminated flyers in which they demanded all the Rockefellers step down from the museum’s board. Through its banking business, the wealthy family was indirectly involved in the Vietnam War and the artists accused the museum of taking blood money. Both attacks on the museum can be considered artistic formulations of institutional critique.

Shocking institutional critique: blood all over the foyer of the museum

The inspiration behind these actions, as the name of the group suggests, were the guerilla tactics that were originally an element of warfare (‘guerilla’ comes from the Spanish meaning ‘little war’). The aim of guerilla tactics is to achieve military successes, despite inferiority of numbers, by means of well-planned, sudden attacks. These sorts of strategies became popular among the student revolt generation through the writings of Che Guevara. (Incidentally, GAAG repeatedly emphasized that although they adopted the tactic for their art, they never caused physical harm to anyone in any of their actions.)