“It’s a matter of convenience, I’m always available”, writes young photographer Francesca Woodman in her notebook, and in the lightness of her words formulates the credo of more than 150 years of female photography. In front of and behind the camera, model and creator – this dual-role is one that female photographers adopted decades before Woodman, and their self-conception has influenced women above and beyond this medium. Artists like Claude Cahun and Germaine Krull, later followed by Woodman, Birgit Jürgenssen, Hannah Wilke and Cindy Sherman, and now Petra Collins in the digital selfie, use the camera to explore their own identity, capturing themselves in the mirror or using the self-timer.

Francesca Woodman, self-portrait talking to Vince, Providence, Rhode Island, 1977, image via vogue.com

Apparently unashamedly they put themselves and their bodies on show to the observer, yet their images are more than mere documentation of narcissistic human beings. Rather, as in other examples from the exhibition “ME” at the SCHIRN, these female artists take the self-portrait well beyond its classic definition. In doing so, they open up a further level of duality: of the subject versus the object, embodied in just one person, or more precisely, one woman. In photography, they appear to have found the ideal medium, and with their bodies their most important tool.

The New Women

This (self-)conception found its outlet in the beginnings of photography, which suddenly gave women a welcome, experimental freedom. Before it came centuries of painting and sculpture – and thus centuries of clearly defined roles: the man as the creator, as genius of picture and form, and the woman as his favorite subject. Female painters and sculptors, on the other hand, were always to remain in the minority.

The development of photography changed all this. It was precisely because photography was not considered an art form for several decades that women were able to use it uninhibitedly to capture their world, other people and even themselves. Here the medium in itself has been made a theme time and again, for example as early as the end of the 19th century by the Comtesse de Castiglione, who had herself photographed with a picture frame held up in front of her, and thus hinted at the staging of her feminine beauty through the photograph.

Reflection on the medium

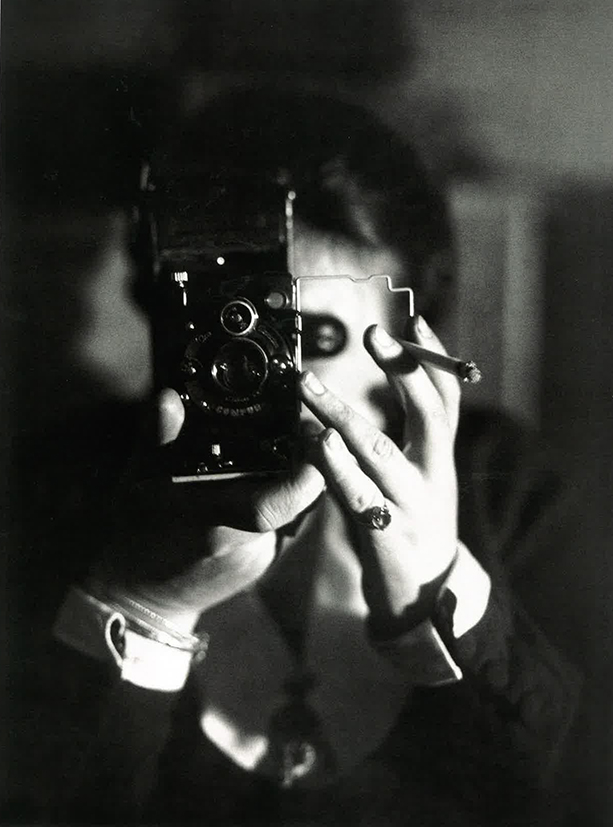

In Germany the tradition of such photographs was picked up on in the 1920s and 1930s in particular by the female photographers of a new generation, the so-called “Neue Frauen” or “New Women”. They staged self-portraits, working with mirrors, masks and various spatial concepts, which function as a moment of self-interrogation and reflection on a profession as well as the medium. Their best-known representatives included Berlin-based photographer Germaine Krull – in a way the prototype of the self-confident “new woman” who, through her professional war reportage, conquered one of the domains of male photography for herself.

Pierre-Louis Pierson, Countess Virginia Oldoini Verasis di Castiglione (1835–1899), Image via metmuseum.org

For her monochrome “Self-portrait with Ikarette”, she photographed herself in a mirror in 1925: a hand-camera covers her face almost entirely, although the lack of focus makes it barely recognizable. On the one hand a professional portrait, with Krull documenting herself here using her essential tool and once again making the staged framework of the medium explicit. On the other hand, it likewise traces reality from another angle, as Krull’s self-portrait becomes a manifestation of the new image of woman. The mirror that is implicit here remains a popular tool among contemporaries like Ilse Bing, Florence Henri and Lotte Jacobi.

An imagery of their own

It was not only the mirror that the artists of the late 1960s and 1970s were to pick up on once again, and whose effect they would develop further by means of a role or masking; they were also to carry forward the tradition of self-interrogation in the form of the self-portrait. Under the influence of the civil rights, anti-war, 1968 and women’s movements, a “feminist avant-garde” emerged (the name was coined by the art critic, publicist and director of the VERBUND collection, Gabriele Schor, in the context of the exhibition of the same name in 2015) – an intellectual community whose pioneers generally deconstructed society’s image of women independently of one another and sought new representation for women. They included artists like Lynda Benglis, Suzy Lake, Eleanor Antin, Hannah Wilke, Martha Rosler, Cindy Sherman, Birgit Jürgenssen and even VALIE EXPORT. They thus developed their own imagery, which Francesca Woodman would pick up on a few years later.

Germaine Krull: Self-portrait with Ikarette, ca 1925, image via coxorange-berlin.de

Here the female body is increasingly instrumentalized: its limitations sought, its surface used as a canvas or clothed, its traditional role as an object (to be looked at) debated. The woman as a mother, a wife and housewife, and/or a sexual, “beautiful” object – in order to dispel these stereotypes, female artists choose performance, video art and – still – the self-portrait in photography. This is the case, for example, in the early “Bus Riders” series, or the subsequently renowned “Untitled Film Stills” by “costume artist” Cindy Sherman, in the scenes set by Hannah Wilke, in the often ironic, multi-layered self-portraits by Austrian artist Birgit Jürgenssen (for example with Jeder hat seine eigene Ansicht – “Everybody has their own opinion”), or even in the work of Francesca Woodman. With just a few exceptions, Woodman always sets the scene for herself in front of the camera, and with penetrating imagery opens up cultural-historical points of reference as well as questions about the self. She debates the relationship of the body to the space and its dissolution in her self-portrayals – and in doing so, calls into question the classic definition of the self-portrait.

The conception of photography

Thus photography makes it possible for all the artists to shift their act of performance from the public to the private sphere, to their studios and homes, and for the public to nevertheless be given access to it. The core slogan of the women’s movement, that “the private is political”, thus becomes fact in the art of the “feminist avant-garde” of the 1970s and subsequent years.

Cindy Sherman, from the series Bus Riders, image via prezi.com

As something that had not always been so, the preliminary work of those female pioneers changed the understanding of photography in the following decades to such an extent that subsequent generations sometimes unwittingly follow their tradition. Indeed, less politically, yet still with the opening up of the (seemingly) intimate private sphere, today a new generation of female photographers is at work – a generation of young women who capture themselves and their female environment with the cameras of their cell phones, who are becoming known via Instagram and other social media, who are less keen to redefine their political-social role. Instead they revolt – with photographer Petra Collins leading the way – against the Photoshop-based, stick-thin beauty ideal propagated by advertising and the consumer society. However, to do so they still use the close-at-hand tools just as decades before: photography and their own bodies – in all their unvarnished, warts-and-all, post-pubescent, apparently imperfect naturalness.

Petra Collins, from the series Selfie, image via petracollins.com