A robot runs through a forest, humanlike on two legs, closely followed by a camera. Tubes protrude from its back, extending beyond the edge of the picture to the control module. It is indeed a short but bleak sequence that Pedro Barateiro (born 1979) presents in his video piece “The Opening Monologue” (2018) to the viewers. The robot simply keeps running steadily and enthusiastically, as if it were about to turn around at any moment and proudly look the spectator in the face, expecting praise.

It just so happens that a machine does not know that it is running, let alone have a notion about what running means. It is not proud of what it does, it merely follows instructions. Everything else is human interpretation, rationalization and projection, which brings us pretty much to the heart of the topic of “The Opening Monologue”. “I don’t know about you but I try hard to think on how language colonizes us, our words and ideas” we hear the narrator say thoughtfully off screen. The narrator introduces himself as a cyborg: “I’m speaking from my computer, but I’m writing with a golden pencil,” as he explains mysteriously at one point.

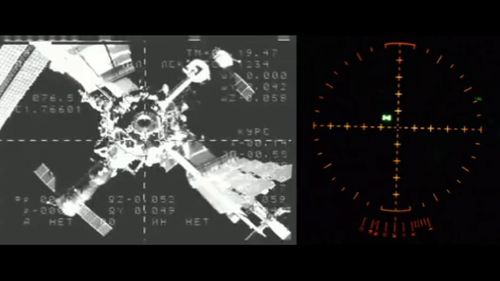

The video work consists of a collage of GIFs and Found Footage material

In his multi-media works Portuguese artist Pedro Barateiro addresses structures and mechanisms in post-capitalist societies. In his solo exhibition “Theatre of Hunters” (2010), for example, he explored images, documents and literary texts in terms of the role they play in defining the reception of reality. The almost 15-minute video work “The Opening Monologue” consists of a collage of GIFs and other Found Footage material from the Internet.

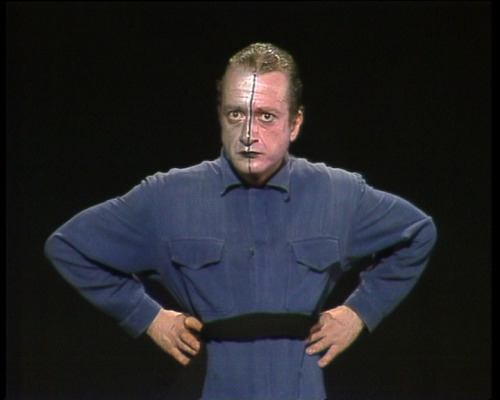

Pedro Barateiro, Theatre of Hunters, 2010, Image via tumblr.com

Images of robots and photos of the ISS space station alternate with the typical Internet memes, we all are bombarded with on a daily basis.

The cyborg’s narration meanders between culturally pessimistic and cryptic statements about the world, communication, the zeitgeist, the social order and freedom, whereby things are deliberately kept eccentric and ambiguous. For example, we hear the words: “I never forget Frantz Fanon’s words: ‘Every spectator is a coward or a traitor’” and “We know by now that every word written is both fictional and real.” However, as the narrator emphasizes, this refers neither to the opening monologue that gives the work its title, nor to a “hypnosis session” with the narrator’s own therapist or the like. What the narrative presented here is supposed to be in formal terms, remains undecided. “The Opening Monologue” is framed by the story of US programmer and hacktivist Aaron Swartz, to whom Barateiro dedicated the work.

I’m speaking from my computer, but I’m writing with a golden pencil.

In 2011, there was a great stir when the Net activist was arrested after using free Internet access at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) to download countless otherwise to-pay scholarly articles from the online JSTOR library and making them available to the public. The investigations by public prosecutors took almost two years. Swartz committed suicide before his trial began. Presumably for this reason, too, he has since been regarded by many as “the first martyr of the freedom of information movement” as the Israeli historian Yuval Noah Harari referred to him.

Pedro Barateiro, The Opening Monologue (Still), 2018, Courtesy of the artist and Netwerk Aalst, Image via tumblr.com

In an accompanying article Pedro Barateiro describes “The Opening Monologue” as an attempt to dismantle “our colonized imagination”, to de-program charged messages which cloud our human perception, experiences, and actions. In this sense Aaron Swartz’ action of making information available without the commentary and its often ideologically classifying connotations, serves Barateiro as an example of a de-colonization of language. The artist, however, views the currently so often used concept in a far more fundamental sense than others: For him, any language is colonized that is used politically and promotionally, regardless of what the actual intentions are.

One could say that the cyborg’s narrative, and it is in places puzzling, is also permeated by a knowledge of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s philosophy of language, in which the philosopher pointed to the problems of conveying meaning within language in general: “Propositions cannot represent the logical form: this mirrors itself in the propositions, That which mirrors itself in language, language cannot represent. That which expresses itself in language, we cannot express by language.”

Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.

The logical form in this case refers to the structure of a fact, in other words the circumstances of the world – which can be described, but not represented by language. As such, the cyborg’s last words are as reconciliatory as they are irresolvable: “I’m with you. And we’re being eaten by words.”

You see a smoking Godard at the Lake Geneva

Pedro Barateiro has chosen Jean-Luc Godard’s 1995 film “JLG/JLG - autoportrait de décembre” as his favorite movie. Even though in its title the work promises a self-portrait, what we have here is not a classic talking-heads documentary in which the director discusses himself and his creative output. Rather, it is a filmic collage, which attempts in images and language to explore what forms an enquiry into your own personality can take. We see Godard, at the time still chain-smoking, in his home on Lake Geneva, his apartment crammed with books and the TV on in the background.

The off-screen comments oscillate between philosophical comments, attempts to categorize current political events and self-reflective statements – as is typical of Godard, echoing quotations that at first sight are not always recognizable as such. And in some scenes the filmmaker also refers to production conditions in the cultural world. Here, again, Wittgenstein pops up again at some point: All an artist’s aspirations thus perhaps briefly appear to be a struggle against Wittgenstein’s statement that we can only talk meaningfully about facts: “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.”