While Russia’s war of aggression on Ukraine has had the global public in a state of shock since February 2022, another piece of horror news repeatedly made headlines in June: Grain shipments from Ukraine, the so-called breadbasket of the world, were rendered virtually impossible by the bombing of the port city of Odesa; this subsequently threatened to cause a global hunger crisis. In the background, alternative plans were already being drawn up to get the grain out of the country on train tracks via Romania. An overgrown rail route that had been unused for decades, still with the wider gauge that was standard in the former Soviet and Eastern bloc countries and leading to Galati in Romania, was made ready to run again within a very short time. At the same time, the Romanian Minister of Transport promised further modernization of the transport infrastructure, and alongside the concrete aid entrepreneurs sensed good opportunities for new areas of business.

A similar simultaneity of war, political upheaval, and economic prospects also runs through Tekla Aslanishvili’s work “A State in a State” (2022), in which she takes a closer look at the difficult processes of a completely different train route, namely that of the new Silk Road where Georgia, Armenia, and Turkey meet.

A perpetual flow of countless freight trains

“How Azerbaijan, Georgia, And Turkey Subverted Russia And Isolated Armenia With New Railway,” was the title of a 2017 article in the U.S. business magazine “Forbes”, reporting on the opening of a new rail link between the three countries. Succinctly named the BTK, the train link runs from Baku in Azerbaijan, through Georgia’s capital Tbilisi, to the Turkish city of Kars, and thus connects the Caspian Sea with the gates of Europe. In doing so, it plumbs new trade routes with the aim of undermining Russian supremacy in the region, while excluding Armenia from economic developments. The idea began to take shape back in 1993, when the long-simmering Nagorno-Karabakh conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan escalated into armed conflict. In a show of political support for Azerbaijan, Turkey at the time shut down a rail link that was similar but ran through Armenia. And so it is shots of the freight station in Tbilisi that open Georgian artist Tekla Aslanishvili’s experimental documentary “A State in a State”, while she reflects off-camera on the continuous flow of countless freight trains passing through the Georgian capital.

The film is a kind of search along the BTK train route, approaching the difficult political-social interconnections of the post-Soviet states and aiming to capture them with the help of various interlocutors – journalists, track workers, and researchers. As with Aslanishvili’s other cinematic works, the project is based on extensive research conducted by the artist together with Dr. Evelina Gambino, a research associate at Cambridge University in England.

In previous works, too, Tekla Aslanishvili has pursued a similar approach: In “Transparent Cities” she researched an abandoned house as part of an artist residency, and in “Trial and Error” the artist dealt in depth with the Georgian planned city of Anaklia, the implementation of which has failed time and again for over 20 years. In documentary as well as carefully staged film footage, the work traces the economic implications of the construction of the railway line and takes a close look at the regional subsidy policy. At the same time, “A State in a State” also focuses on the tangible impact on the multi-ethnic local population and traces the transnational solidarity between track workers. In her work, Tekla Aslanishvili thus provides an impressive insight into the region between the Caspian and the Black Sea, including with the help of sophisticated sound design.

Between cultural imperialism and the export of ideology

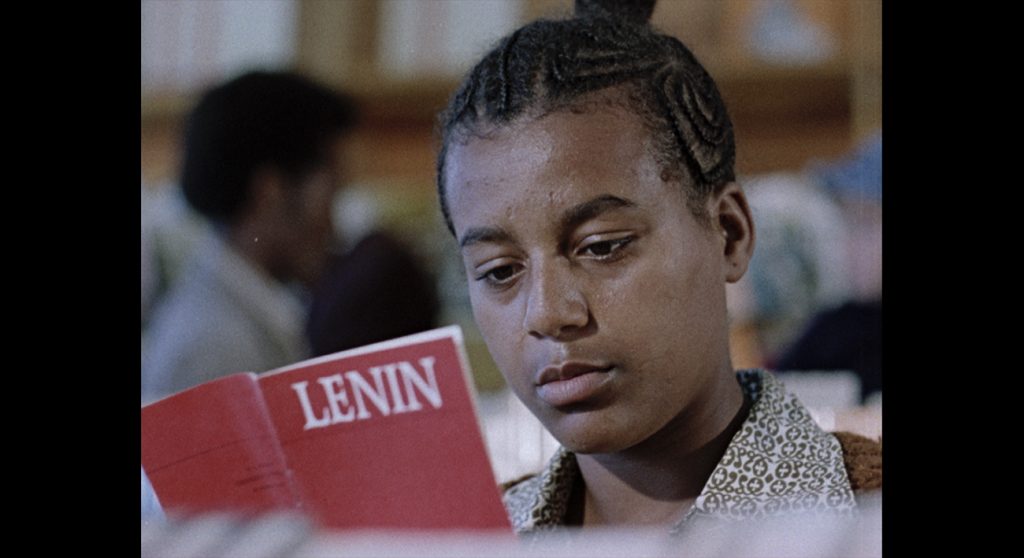

As a second film, Tekla Aslanishvili has chosen “Red Africa” (2022) by Russian director Alexander Markov. Markov had come across any amount of archive footage in a film archive produced back during the Cold War in various African countries between 1960 and 1990. In “Red Africa,” the director weaves the propaganda material documenting the Soviet Union’s activities in countries that had just freed themselves from colonialism into an elaborate montage reflecting on cultural imperialism and the export of ideology. Without commentary, the footage shows a continuous stream of Russian delegations paying visits to the leaders of the newly created nations, while on the ground Soviet goods find new customers and economic sectors are tapped. At the same time, the local population was given the opportunity to study at Russian universities, and so the historical film material also documents the meeting of individuals who, just a short time before, had been worlds apart.

However, the fact that this cultural exchange is almost without exception one-sided, flowing from the USSR to the African states, is unmistakably imprinted in the excerpts. The last part of the film harks back to the beginning of “Red Africa,” which depicts in vivid images the celebratory mood in the newly founded African states, which have finally rid themselves of Western colonialism. Now though, we see footage of demonstrations from the states of Soviet internal colonialism, that continental expansion which the USSR itself had pursued for decades and which gradually collapsed in the early 1990s. Both Alexander Markov’s film montage and Tekla Aslanishvili’s “A State in a State” thus provide insights into complex discourses that have long received little attention.

Alexander Markov, Red Africa, 2022, Film still, Image via cineblogifilnova.fcsh