How many photos of cute animals, fluffy puppies, or playful cats have we got on our smartphones? Snapshots of our own pets or the neighbor’s adorable dog have long since festooned our latest profile photos on Tinder or our Insta-stories. Yet our obsession over pets dates back far before the digital age. Since time immemorial, artists have captured their close relationships with their pets, painted commissioned portraits of noblemen with their four-legged companions, or deliberately depicted the relationship between people and animals. Here is our top ten!

1. Paula Modersohn-Becker, Cat in Child’s Arm, around 1903

Paula Modersohn-Becker was so inspired by the togetherness of people and animals that she completed numerous portraits between 1902 and 1905 depicting children with animals. Around the year 1905, she painted a blond girl in a red dress with a cat lying in her arms. The girl’s hold seems clumsy, and the cat appears almost to be sliding out of it; in other words, Modersohn-Becker captures a moment that could be gone in the blink of an eye. With her choice of figures, she focuses on creatures that otherwise rarely radiate calm. Perhaps the cat is trying to get away or wants to chase a mouse…

2. Robert Mapplethorpe, Snakeman, 1981

Robert Mapplethorpe’s “Snakeman” is one of those portraits in which the American photographer depicts his models with attributes of seduction. The unknown young man wears a black leather mask of a satyr (= devil) that is reminiscent of fetish objects, while the snake – a boa constrictor – winding almost Mannerist-like around his shoulders can be interpreted as a phallic symbol. Here, Mapplethorpe combines Christian motifs with themes like fetishism, sex, and seduction. Have the devil and the serpent entered into a covenant? Or is the boa constrictor still setting itself up for a deadly stranglehold?

Robert Mapplethorpe, Snakeman, 1981, Tate © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, image via tate.org.uk

3. Goya, Manuel Osorio Manrique de Zuñiga (1784–1792), 1787–88

This brown-haired young man in the splendid red costume is gathering a little zoo around himself. The son of the Count and Countess of Altamira stands between a cage full of finches and three cats with big, bright eyes that seem to be fixated on the magpie, the boy’s pet. In Christian iconography, birds often represent the soul, while in baroque art birds in cages symbolize innocence. Perhaps behind the choice of animals is Goya’s intention to illustrate the transience of innocence and youth. In its beak, incidentally, the magpie holds Goya’s calling card. Even in the 18th century, people knew a thing or two about self-promotion!

Francisco de Goya y Lucientes, Manuel Osorio Manrique de Zuñiga, 1787–88, The MET, image via metmuseum.org

4. Maria Lassnig, Self-portrait with Monkey (Beloved Forefathers), 2001

Am I still beautiful? It was back in the 1940s that Maria Lassnig began to demonstrate a new way of representing physicality in her works. She painted not what she saw, but rather what she felt, so she also used colors to depict certain emotions. In her “Self-portrait with Monkey”, she portrays herself as an old woman with sunken cheeks and pointed shoulders. A monkey rests on her lap, ruffling its hair. What does the monkey represent? Vanity? Or perhaps, as the animal closest to humans, it represents the inner life of the artist. From the late 1990s onwards, Lassnig increasingly painted self-portraits with an animal that often represented introspective experience.

Maria Lassnig, Self-portrait with Monkey (Beloved Forefathers), 2001, Städel Museum, image via marialassnig.org

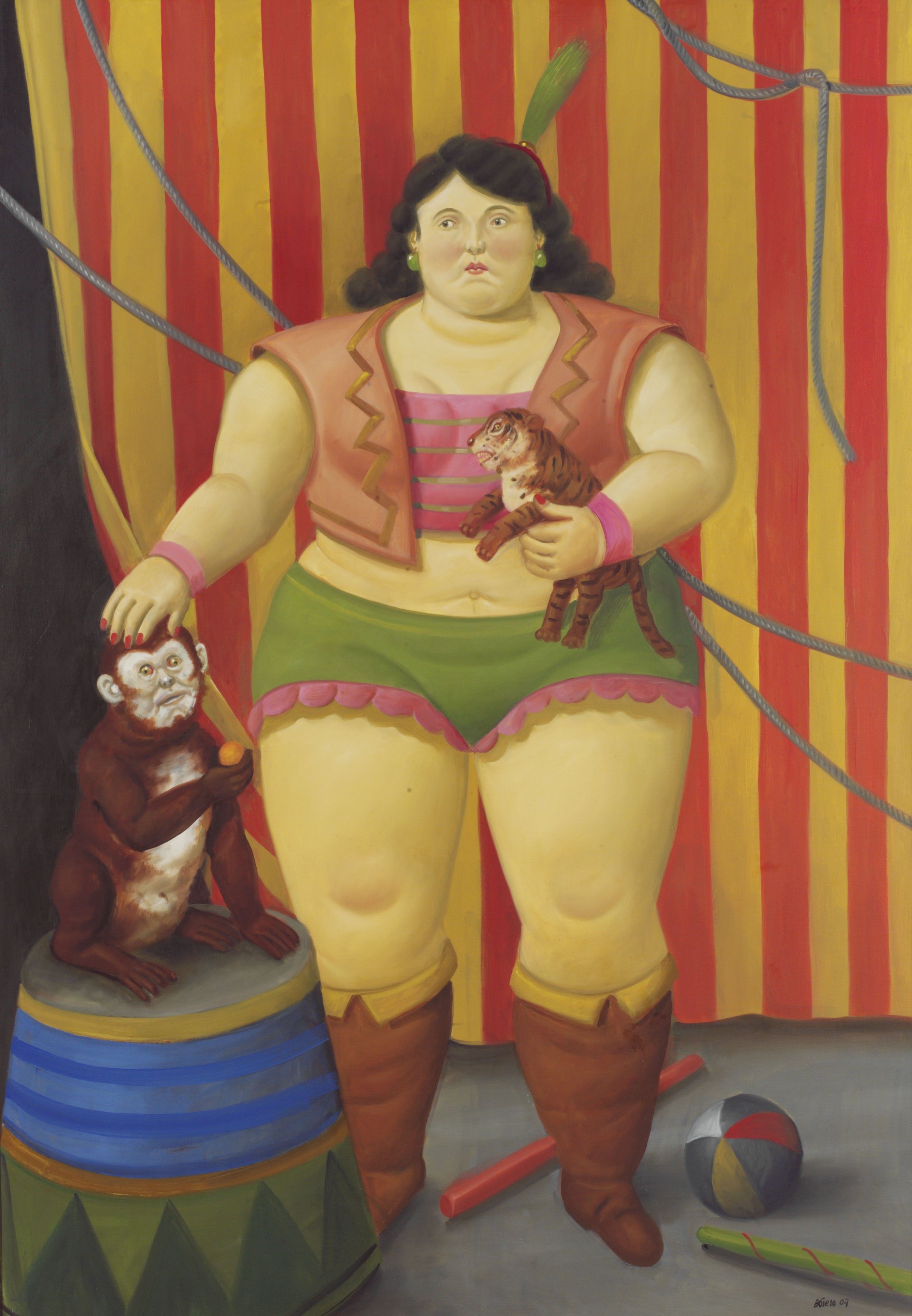

5. Fernando Botero, Circus Girl with Pet, 2008

A chance encounter with a traveling circus in Mexico gave Columbian artist Fernando Botera the inspiration for his series of works known as “The Circus”. Botero’s unmistakable style is characterized by round, seemingly inflated figures, pervasive colors, and absurd proportions and it also features in “Circus Girl with a Pet”. A scantily clad, Baroque-seeming girl eyes the observer seriously and a little sullenly. With her right hand, she pets a tame monkey, while her left arm cradles a miniature tiger. Botero’s depiction of circus artists is reminiscent of the fin-de-siècle interpretations of the genre by artists such as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, who captured circus life in his drawings and paintings in a decidedly unglamorous and unadorned manner.

Fernando Botero, Circus Girl with Pet, 2008, image via operagallery.com

6. Leonardo da Vinci, Lady with an Ermine, 1489–1490

Who is stealing whose thunder here? In Leonardo da Vinci’s portrait “Lady with an Ermine”, the ermine of the title is anything but randomly chosen. Ultimately, it even helps us to identify the mysterious woman. It was only in the early 20th century that researchers discovered that the portrait depicts Cecilia Gallerani, one of the mistresses of Ludovico Sforza, Duke of Milan. In 1488 Sforza, who was better known as “Il Moro”, was awarded the Order of the Ermine, which earned him the nickname “Ermellino Bianco” (“white ermine”). But there are etymological clues that point to Cecilia Gallerani, too: The ancient Greek word for weasel is galê or galéē, so this can be understood as an allusion to her surname. Leonardo, who had a penchant for wordplay and secret messages, knew how to use the white ermine to incorporate Ludovico symbolically and secretively into the portrait.

Leonardo da Vinci, Lady with an Ermine, 1489–1490, image via wikiart.org

7. Pieter Hugo, Mallam Mantari Lamal with Mainasara, Nigeria, 2005

In his series “The Hyena & Other Men”, South African photographer Pieter Hugo depicts a group of men with their hyenas to impressive effect. A journalist friend of Hugo’s drew his attention to a group of Gadawan Kura (“hyena men”) in the Nigerian capital of Abuja. The group comprised men, a little girl, three hyenas, four monkeys, and rock pythons, and made a living by performing and selling traditional remedies. For two years, Hugo travelled through the country with the group for several weeks at a time, capturing the men and their animals for posterity.

Pieter Hugo, Abdullahi Ahmadu with Mainasara, Nigeria, 2005, image via pieterhugo.com

8. Frida Kahlo, Self-portrait with Monkey, 1945

Frida Kahlo minus her animals – inconceivable! In many of her self-portraits, the Mexican artist is flanked by monkeys, cats, or exotic birds. In her “Self-portrait with Monkey”, she is depicted with her pet monkey Fulang Chang. This animal companion, whom Frida Kahlo first captured in a self-portrait in 1937, can be interpreted as an alter ego; even the hairstyles of the two are similar. With a friendly, protective gesture, Fulang Chang holds his arms around the physically battered artist. While monkeys are often considered to be stubborn and insolent, Kahlo paints a different picture with her friendliness towards them. For her, spider monkeys are tender, gentle creatures. In Mayan culture, they stand for joie de vivre, engage in mischief, and are associated to a great extent with lust and fertility.

Frida Kahlo, Self-Portrait with Monkey, 1945, Robert Brady Museum, photographer: Tachi © 2014 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, Image via news.artnet.com

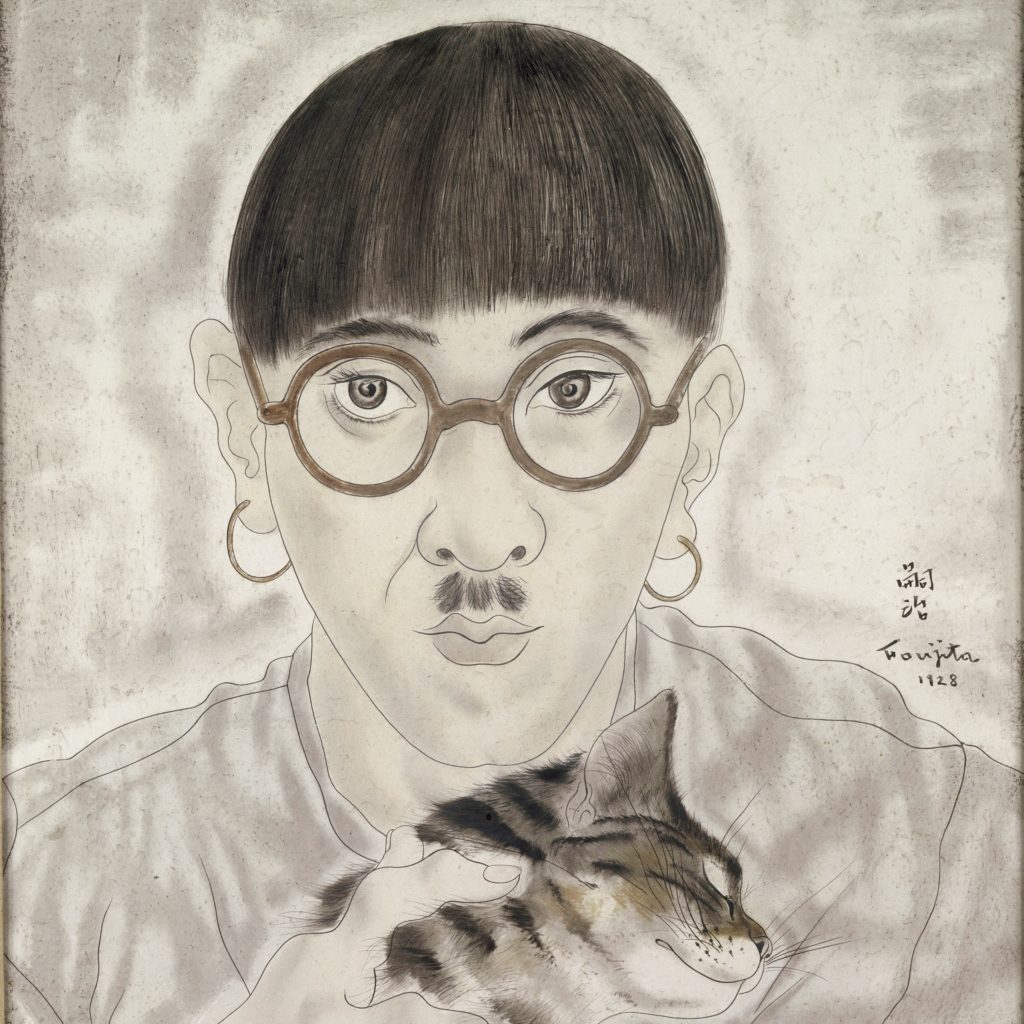

9. Leonard Tsuguharu Foujita, Self-portrait, 1928

Foujita was a true cat-lover. He painted and drew them incessantly, including in his self-portraits. One day, Foujita was followed by a cat as he made his way to the studio, whereby the cat gained not only a master but also the name Mika (Japanese for “striped”). Foujita was fascinated by the animals’ independence and unpredictability and continually compared them to the “female character”: According to tradition, he supposedly believed that cats were related to women, claiming that God had given people cats so that they could better understand the mysterious female nature…

But a resemblance of a different kind was also identified by the artist’s friends, who joked that he even looked like a feline. Birds of a feather flock together!

The reason why I so much enjoy being friends with cats is that they have two different characters: a wild side and a domestic side.

Léonard Tsuguharu Foujita, Self-portrait, 1928, Fondation Foujita, image via dailyartmagazine.com

10. Gustave Courbet, Frau mit Papagei, 1866

Spurred on by the success of Alexandre Cabanel’s “Birth of Venus” at the Paris Salon of 1863, Gustave Courbet then strived to challenge the Academy with a more realistic nude painting. The first attempt in 1864 was rejected, but in 1866 the jury accepted “Woman with Parrot”. This time too, though, there was a hail of criticism lamenting Courbet’s “lack of taste”, the “awkward” pose, and the model’s “disheveled hair”. The younger generation of artists, however, who shared Courbet’s disregard for academic standards, found this more naturalistic painting very appealing. It is not only the model’s apparently spontaneously discarded clothing that sets the painting apart from the mythological and idealized nudes otherwise exhibited in the salon, but also, as one advocate praised, that it was primarily a depiction of “a woman of our time”. As for the brightly colored parrot: This can be interpreted as a phallic creature, on the one hand, or compared with the painter’s color pallet on the other.

[Translate to English:]

Gustave Courbet, Frau mit Papagei, 1866, The MET, image via metmuseum.org

[Translate to English:] DOGGY BONUS!

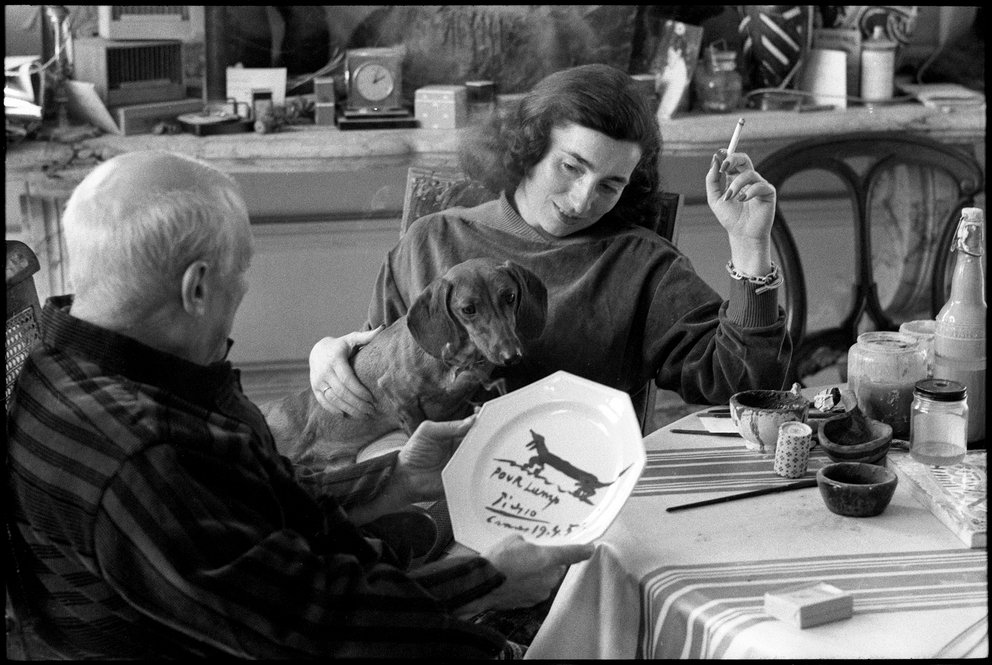

Picasso und Lump

Meet Lump, the most important animal model in art history! When Lump and Picasso first met in 1957 at Picasso’s villa in the hills around Cannes, it was love at first sight. Lump’s actual owner David Douglas Duncan travelled with his dog to the south of France to photograph Picasso at his property, and as they lunched together Picasso enquired whether Lump had ever had a plate of his own. When Duncan said he hadn’t, Picasso grabbed his paints and brush and painted a portrait of Lump on his plate, subsequently giving the dated “work” to Duncan. For reasons not entirely clear, Lump then spent the next six years with Picasso, living alongside the artist’s boxer Yan and a goat named Esmeralda. Duncan said of Lump and Picasso: “This was a love affair. Picasso would take Lump in his arms. He would feed him from his hands. Hell, that little dog just took over. He ran the damn house. Picasso had many dogs, but Lump was the only one he held in his arms.”

David Hockney’s Dog Days

David Hockney also developed a love of dogs and in the 1990s made countless drawings and paintings of his dachshunds Stanley and Boogie. His figurative works appear almost a little old-fashioned in the context of the 1990s, although he found a good explanation for this: “I make no apologies for the apparent subject matter. These two dear little creatures are my friends. They are intelligent, loving, comical and often bored. They watch me work; I notice the warm shapes they make together, their sadness, and their delights. And, being Hollywood dogs, they somehow seem to know that a picture is being made.” Hockney’s dog pictures were published in 1998 in the book “David Hockney's Dog Days”.

Jacqueline Roque and Lump, Pablo Picasso inspects the plate he has just painted for and dedicated to Lump, April 19th, 1957 © David Douglas Duncan, Image via utexas.edu

David Hockney and his dogs.Photo: Richard Schmidt, Image via www.architecturaldigest.com