Our history of sound is imbued with political significance. Musicians, activists and artists express their dissent not only in verbal, but also in tonal articulations. And it is fairly common to find political topics in Sound Art, with different fields of conflict such as exclusion, power, migration or war being explored using acoustic means. Although the artistic spectrum is extremely broad, and the approach might vary, it is the same question that is repeatedly asked, namely ‘How can sounds and noises point to certain events, everyday life in a social context and political actions?’

It was the opening up of Sound Art to ordinary, everyday noises that provided the decisive stimulus. When during the performance of “4′33″” (1952) John Cage confronted the audience solely with sounds from their surroundings, he effectively expanded music to include noise and paved the way for socially colored sound. The underlying idea still present in contemporary works is that everyday sound should lend reality a voice.

The artists zero in on political issues and the consumer society

In the 1950s and 1960s Happenings and the Fluxus movement resorted to radical performance practices as a means of responding to the opening up of music to include sound. In a dramatic rejection of all the rules of art, Fluxus artists zero in on current political issues and consumer society – whether as the ironically understood “Revolutionsklavier” (1969) by Joseph Beuys, which as a played musical instrument and now an exhibited object sought to counter art’s voicelessness in the age of student protests, or as an admonishing “Lagerkonzert” (1959) by Bazon Brock, a barbed-wire installation intended to reawaken half-forgotten experiences of war.

Joseph Beuys, Revolutionsklavier, 1969 © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2018/courtesy Schirmer/Mosel, Image via sueddeutsche.de

The works, which typically stemmed from other actions, incorporated both sound and silence. Noise, silence or a din were to be understood as a rebellion both against the artistic and musical mainstream and against the prevailing social order. Fifty years later, Sound Art is especially characterized by the local context of the sound in order to comment on political conflicts.

Pedro Reyes turns machine guns into musical instruments

Current examples that rely on found sound melodies include the works by Pedro Reyes and Guillermo Galindo, which can also be seen in the exhibition BIG ORCHESTRA at the Schirn. Reyes uses illegal machine guns seized by the Mexican border authorities to make wind, percussion and string instruments. Galindo tracks down his “border instruments” between national barriers – the American-Mexican border area – and imbues his found items with new musical functions: corrugated iron, chains and tires are to be played like percussion instruments.

Both artists are intent on creating a new context with positive connotations that the objects gain in the art context. The explicit depiction of weapons of war aims not only at highlighting contemporary conflicts and the arms trade in Mexico, but also at transforming something destructive into something productive. For Galindo, who was born in Mexico City in 1960, these sounds conceal stories about political authorities, migration and social reality.

The artists Reyes and Galindo currently on show at the Schirn are not the only contemporary artists to use sound as a medium of criticism. Driven by doubts about political authorities, the latter employ materials and the noises they make as acoustic witnesses and evidence. Take, for example, Lawrence Abu Hamdan, who creates sound analyses for controversial spaces. In 2016 the artist examined the acoustic properties of the Syrian prison of Saydnaya, in which over 13,000 people were executed.

His audio-visual sound installations can even be seen as an urgent call to uncover human rights violations and power abuse. Naturally, new political and social themes have produced a different political sound art, but the eruptive quality of such works lies in addressing unpleasant, explosive and current topics using acoustic tools. It is an open question as to whether noises exist without a social context, but at any rate there seems to be ample confidence in sound.

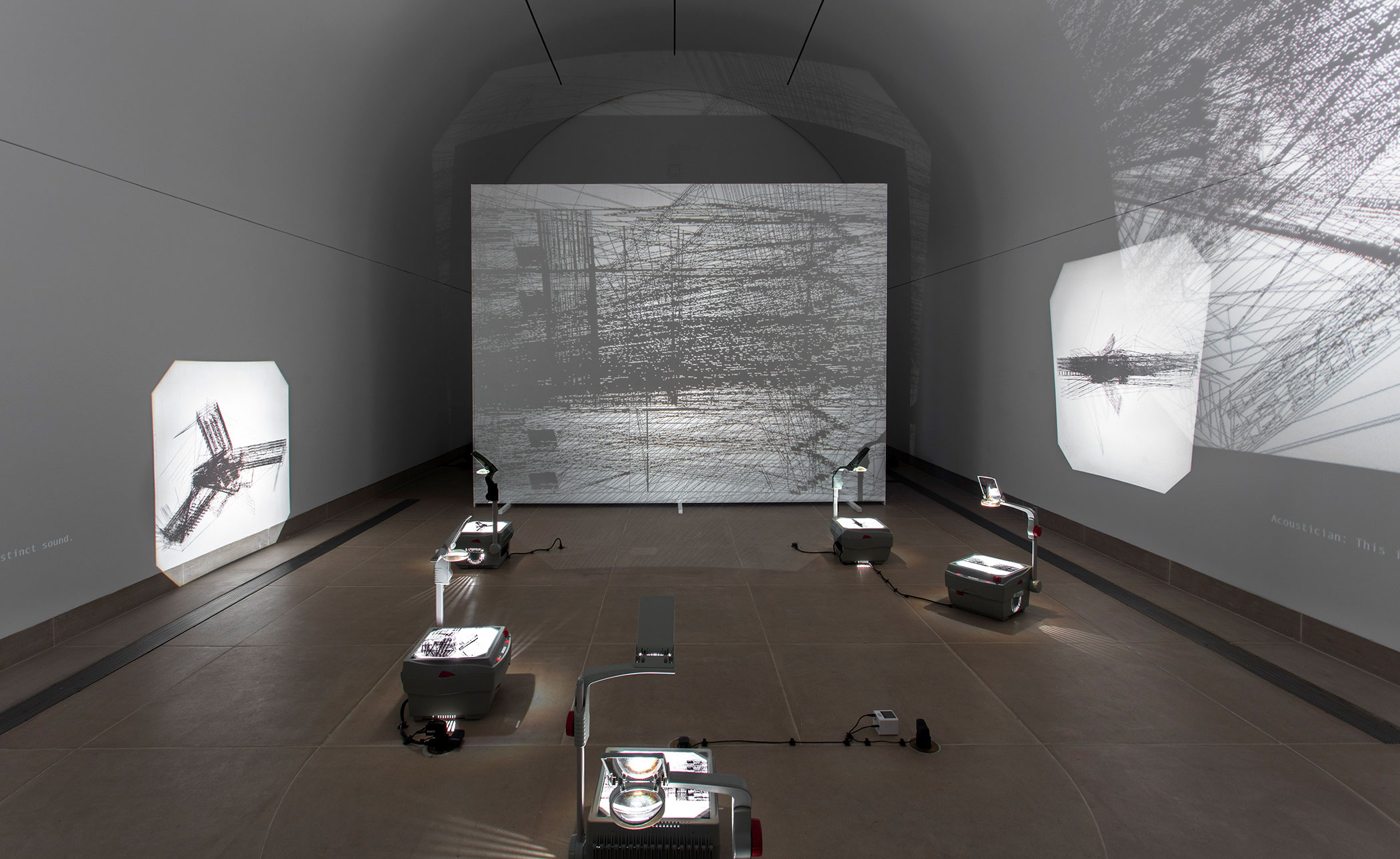

Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Hammer Projects, Installation view, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, January 28–May 6, 2018. Photo: Brian Forrest, Image via hammer.ucla.edu