Who was Suzanne Duchamp? Ingrid Pfeiffer and Talia Kwartler in Conversation

09/11/2025

12 min reading time

Most art lovers are familiar with the name Duchamp, but very few associate it with the artist Suzanne Duchamp. In this interview, curators Talia Kwartler and Ingrid Pfeiffer reveal the person and art behind this name – and her relationship with her famous brother Marcel Duchamp.

Today we would like to speak about Suzanne Duchamp as a woman artist. At SCHIRN, we have made many exhibitions that show there have been a lit of great women artists in history and we only have to discover them (again): “Women Impressionists” (2008), “Storm Women” (2015–2016) (in Expressionism) or “Fantastic Women” (2020) (in Surrealism). Duchamp feels different to me than many of these women artists. Could you tell us more about Duchamp’s character?

Talia Kwartler

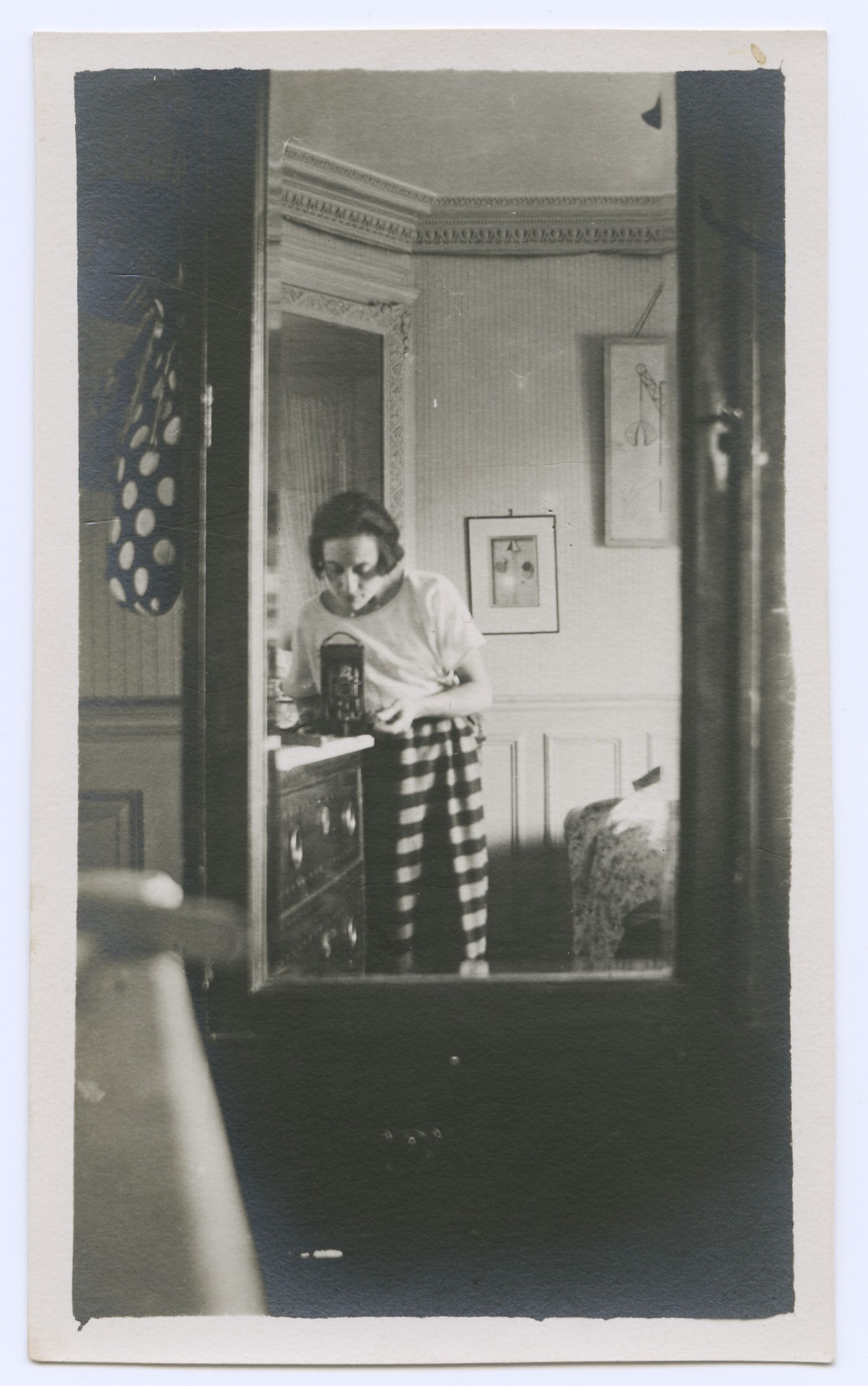

I am glad to begin with this question as it takes us right to the heart of the puzzle that is trying to get to know Suzanne Duchamp today. She left very few personal records and did not preserve any journals that captured her precise state of mind or approach to artmaking. Her letters are spread out in archives across Europe and the United States and from these we can learn more about who she was as an individual. Duchamp had a strong personality with a playful sense of humor. We can find this aspect of her in the photographs that she took of herself and of her family and friends, which make up a substantive part of her personal archives that she preserved. But she is a rather challenging artist to fully understand, and she appears to have intentionally kept parts of her persona more enigmatic and unexplained.

It seems that Suzanne Duchamp was quite self-confident. She had much support from her family from the beginning and could start a career as an artist. She did not struggle as much against limitations. I find this to be very unusual in that period.

Talia Kwartler

We can see Suzanne Duchamp’s self-confidence in how she presented herself in photographs, especially her self-portraits. She was indeed supported by her family in her decision to become an artist, thanks in part to the fact that her three older brothers, Jacques Villon (1875–1963), Raymond Duchamp-Villon (1876–1918), and Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968), had already decided to follow an artistic path. Their father Eugène Duchamp was a local notary in Blainville-Crevon in Normandy, but they grew up in a creative atmosphere as their mother Lucie Duchamp had artworks by her father Émile Nicolle, a well-known painter and printmaker, hung in the family home. Eugène was initially resistant to his eldest sons becoming artists, which is why Villon and Duchamp-Villon decided to take artist names to distinguish themselves. By the time Marcel and Suzanne chose to become artists, their father was done resisting and supported their decision. When Eugène retired and moved to Rouen with his wife and three daughters Suzanne, Magdeleine and Yvonne in 1905, Suzanne enrolled at the École des Beaux-Arts de Rouen, and she became acquainted with avant-garde circles in Paris through her older brothers who were living there. Although Suzanne Duchamp was able to become an artist, she did still face the societal expectations placed upon women at that time; she married a Rouennaise pharmacist, Charles Desmares, in August 1911 and even worked at his pharmacy before they divorced in February 1913 and she moved to Paris.

Was Suzanne Duchamp aware of how lucky she was compared to other women artists? Or did she complain about being less recognized than her brothers and her husband, the artist Jean Crotti?

Talia Kwartler

We cannot say whether Suzanne Duchamp was aware of her good fortune, which began with having been born into such an artistic (and materially comfortable) family. The closeness of the family over the entirety of their lives suggests they very much appreciated this camaraderie on a personal and professional level. Although we do not know if Duchamp counted herself as lucky, we know she did not really complain, at least in writing, about being less recognized than her brothers and her husband Jean Crotti. Of course, it was not uncommon for the male half of modern artist couples to receive more attention than the female half (we can think for example of Sonia and Robert Delaunay and Sophie Taeuber-Arp and Jean [Hans] Arp). In the context of Dada, Marcel Duchamp was, in fact, rather important for including Suzanne Duchamp in early historicizations of the movement that he was involved in organizing the 1950s and 1960s. So we can see that the luck and support of the family system continued for her whole life.

Suzanne Duchamp was part of an artist couple, which was also a typical case for women artists of that period. But it seems that her partnership with Jean Crotti was quite supportive from both sides. Could you tell us more about him?

Talia Kwartler

In contrast to Suzanne Duchamp, Jean Crotti did keep various journals and notes, including an unpublished autobiographical text “Ma Vie,” held at the Archives of American Art in Washington, D.C. We can quickly see from these materials that Crotti was rather focused on himself in his writings. Sensing from their correspondences and personal photographs, Duchamp and Crotti’s marriage seems to have been one of mutual support and appreciation. They were trusty collaborators when they created their artistic movement called “Tabu,” which they presented in an exhibition at Galerie Montaigne in Paris in April 1921. After the couple split with Dada in 1921, they exhibited together again in November 1923 at Galerie Paul Guillaume in Paris, but their artistic paths diverged afterwards as they developed distinctive modes of painting. Duchamp’s post-Dada explorations were more stylistically diverse and overtly figurative; they also maintained the pointed humor Duchamp had developed during her association with Dada. In comparison, Crotti’s art hovered between abstraction and figuration, often with echoes of heads or bodies set within abstract surroundings. It is worth pointing out that Crotti died in 1958, five years before Duchamp did, and that her painting took a marked return to abstraction at this point. They had shared a studio in Neuilly-sur-Seine since the early 1920s, so perhaps his death freed her a bit. Notably, Duchamp played a significant role in advocating for Crotti’s posthumous legacy in the last years of her life.

Before you started your doctoral dissertation about Suzanne Duchamp and Dada at University College London in 2018, you became familiar with her work during the preparation of “Francis Picabia: Our Heads Are Round so Our Thoughts Can Change Direction” (2016–2017) at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Is it true that Francis Picabia was the most influental artist not only for Suzanne Duchamp but also for her husband Jean Crotti?

Talia Kwartler

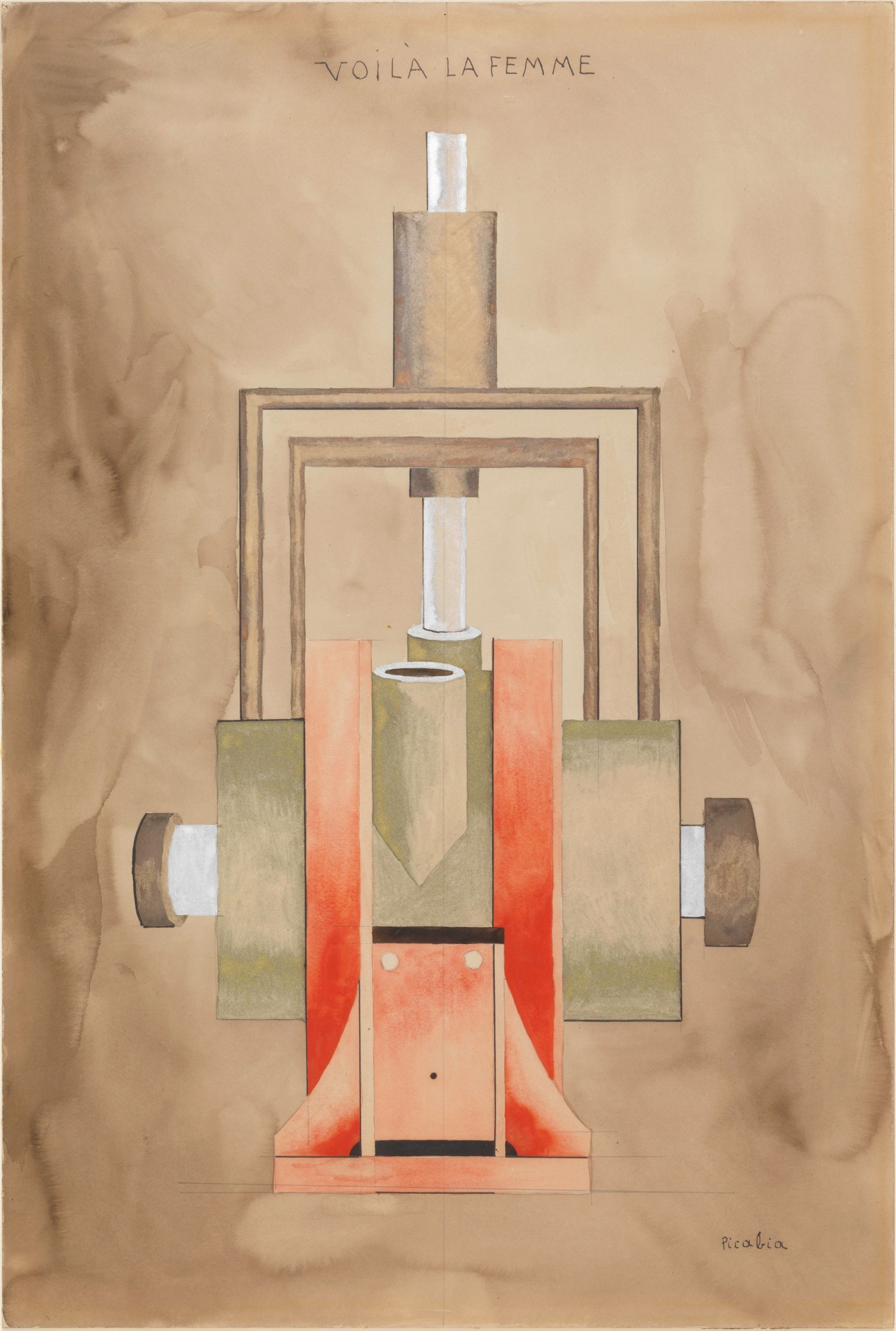

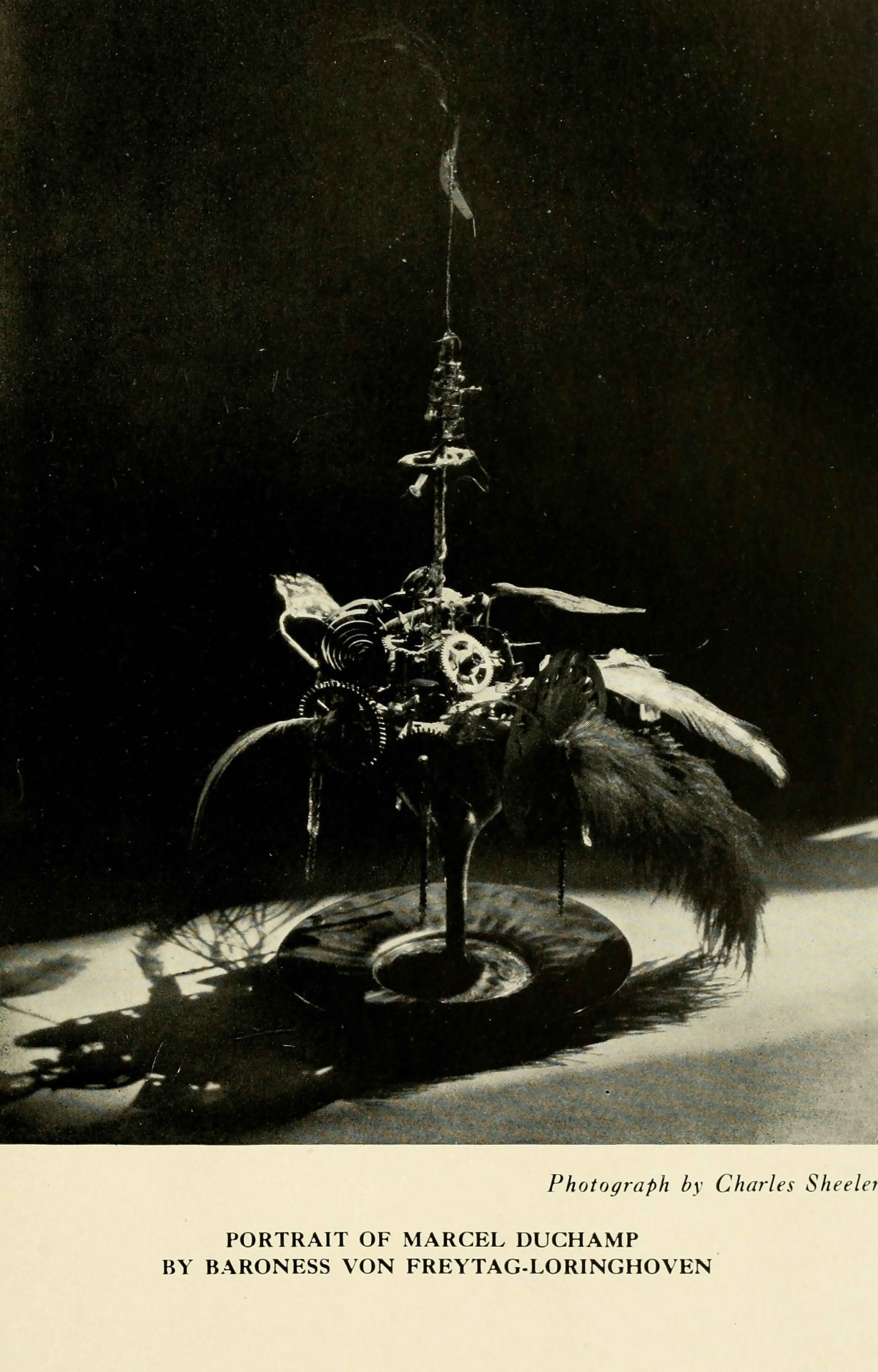

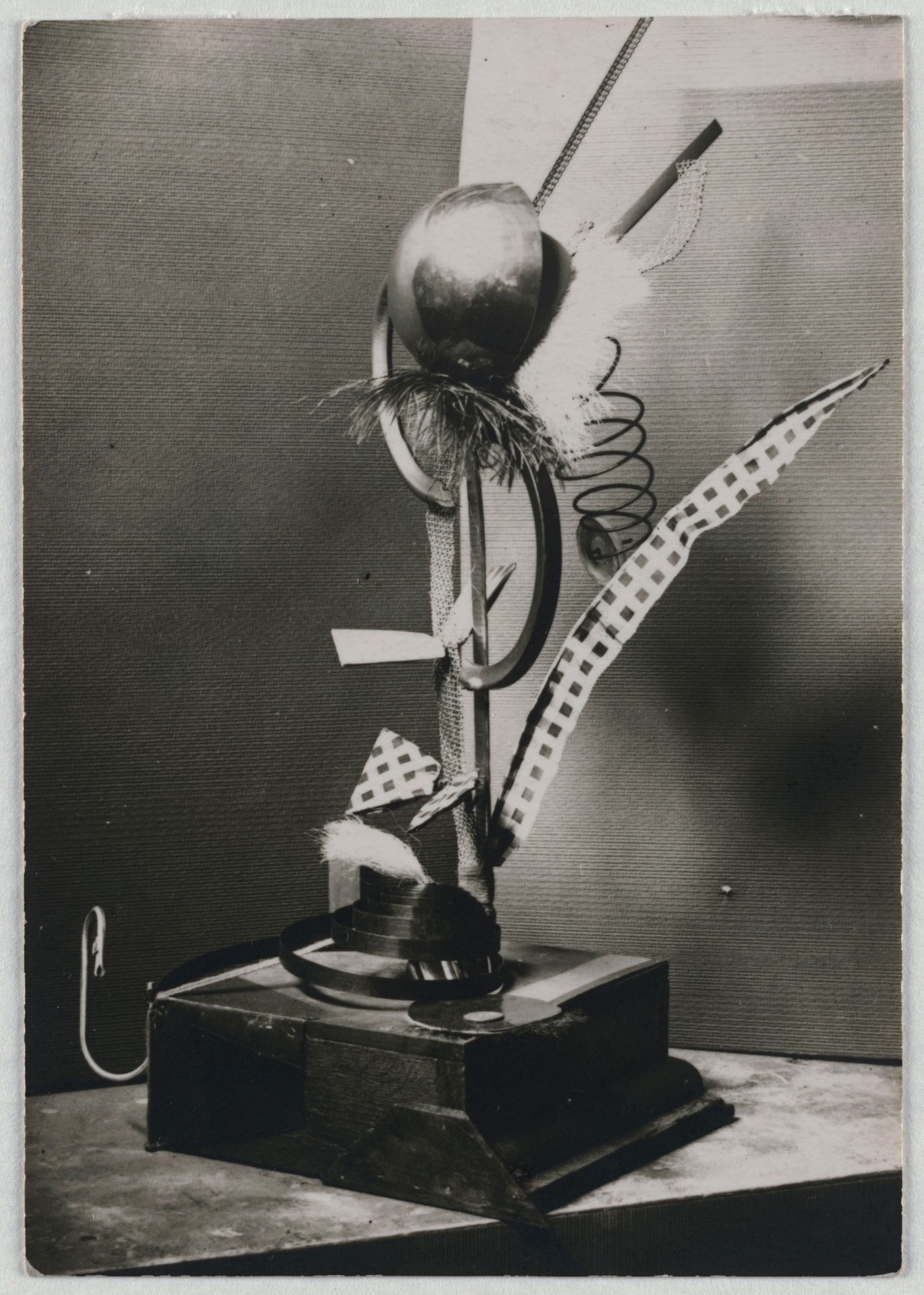

Early on, I found Francis Picabia to be a compelling entry-point into Suzanne Duchamp’s art, not only because they were friends and collaborators, but because it was a way to step aside from narratives about her that had centered around Marcel Duchamp. Having worked for several years on the Francis Picabia retrospective at MoMA, I had become more acquainted with Suzanne Duchamp’s contributions to the Dada movement, and I was very intrigued by Picabia’s irreverent statement about her published in his journal 391 in February 1920: “Suzanne Duchamp does more intelligent things than paint.” I took this as the title for my dissertation because it immediately allowed me to pose the question: So what did it mean for Suzanne Duchamp to do more intelligent things than paint? This made it possible to examine how she probed the potential of painting to turn it into an expansive artistic medium that could encompass many different creative, scientific, and technological realms. The examination of influence has always been less interesting to me than considering the dynamic dialogue that Suzanne Duchamp had with several of the artists she was closest to during this moment, Picabia being central amongst them, but also Marcel Duchamp and Crotti. Often, when influence has been discussed in relationship to Suzanne Duchamp, she ends up characterized as the artist being influenced rather than the artist doing the influencing herself. If we look at historical writings on women Dadaists, such as Beatrice Wood, Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, Hannah Höch or Sophie Taeuber-Arp, we can find a similarly negative situation regarding influence that minimizes their artistic contributions. This is a large part of what I hope to change with my work.

What kind of person was Francis Picabia? Why was he so important for many other artists?

Talia Kwartler

Francis Picabia was an extremely innovative, charismatic, and intense person, who famously wrote “If you want to have clean ideas, change them like shirts.” And he sure did change his ideas often, as well as friends, partners, abodes, and artistic approaches. During the period he was associated with Dada, Picabia served as an important connective figure for the collective both because of his ideas but also because of how his peripatetic movements (from Paris to New York to Barcelona to Zurich to Paris) spread Dadaist principles. His journal 391, which he began publishing in Barcelona in 1917 and continued to publish (albeit intermittently in the later years) in New York, Zurich, and Paris until 1924, served as an important site for creative collaboration and exchange amongst the Dada group and beyond.

Francis Picabia left Dada around 1921 at the same moment as Suzanne Duchamp and Jean Crotti did. Might that be an important influence too?

Talia Kwartler

Francis Picabia publicly split with the Dadaists in the article he published in the newspaper Comœdia in May 1921. Interestingly, Suzanne Duchamp and Jean Crotti had already exhibited their artworks under the banner of “Tabu” rather than Dada, a month earlier at Galerie Montaigne. These artists were extremely close during this period, and often spent time together along with Germaine Everling, Picabia’s partner at the time. So even though Dada scholars such as Michel Sanouillet have pointed to Picabia as a co-instigator of Tabu, this precise timeline suggests this separation from Dada was something shared amongst these friends.

What did you learn during the preparation of “Suzanne Duchamp: Retrospective”?

Talia Kwartler

I was once again reminded how much it matters to look at understudied works of art in person. When I began working on the retrospective with Cathérine Hug from Kunsthaus Zürich in 2019, I had seen a substantial number of the works Suzanne Duchamp made while she was part of the Dada group and a few of her Cubist paintings, as well as some of Suzanne Duchamp’s later watercolors in an exhibition at Francis Naumann’s gallery in New York in 2018. But the paintings Duchamp made in the second half of her career remained largely a mystery to me and there was an absolute paucity of available information about them. I became acquainted with these works mostly through very bad reproductions from auction records on ArtNet that did not do the works any justice at all. I strongly feel that these old images made them rather easy to dismiss. Over the course of the planning for the exhibition, as it moved from a survey focused on Dada to a full-scale retrospective, Cathérine and I became even more convinced that it was important to show the second half of Duchamp’s career and to give people a full view of her art and life. Our show in Zurich and Frankfurt is the first major effort to this end but there remain many important works by Duchamp to locate, which will be greatly helped by the catalogue raisonné of the artist that the Association Duchamp Villon Crotti is preparing.

Has your view of Suzanne Duchamp changed through the exhibition and in which way?

Talia Kwartler

Yes! I find Suzanne Duchamp to be an even more interesting and exciting artist to continue studying. This has often been the case for me: the more I know about her, the more questions I have about her art, and the more work there is that remains to be done. I feel I will only be finished the day that I stop having questions about her to answer and new mysteries to unfold.