The Meaning of ‘Artificial’ Life

05/09/2025

10 min reading time

In her essay “Alter Life”, artist and curator Ala Roushan looks at the extent to which we should rethink our current understanding of what we call ‘living’. The Curator and Philosopher Dehlia Hannah met her for an Interview.

Thinking about Troika’s exhibition “Buenavista”, I was inspired by your essay “Alter Life” to think about ‘alternative intelligences’—something more expansive than ‘artificial intelligence’ or machine learning. AI, in this broader sense, might encompass machine, plant, animal, fungal or other modes of sensing and being. Your essay helped me to reconceptualize AI in this way, and to think about how it holds up a mirror to human modes of consciousness, life, and intelligence. The title holds an intriguing double meaning, however. Can you tell me about the connotations of ‘alter’? Is this short for ‘alternative’? Or is it an imperative: to alter, or change our understanding of life? Or even to alter life itself?

Ala Roushan

I was drawn to the concept of alterity–both intrigued by the sense of otherness in this emerging technology, but also wary of its inherent tendency to alter and transform. I struggled with the term artificial, as it traps us in the dichotomy of natural versus artificial, giving primacy to one over the other. At the same time, I was fascinated and unsettled by the inevitability of radical alterations to our world brought about by this technology. Alterations that became palpable, seeping rapidly into every facet of our existence – from language to social structures to the environment – feeding on the planet’s resources and reshaping our realities.

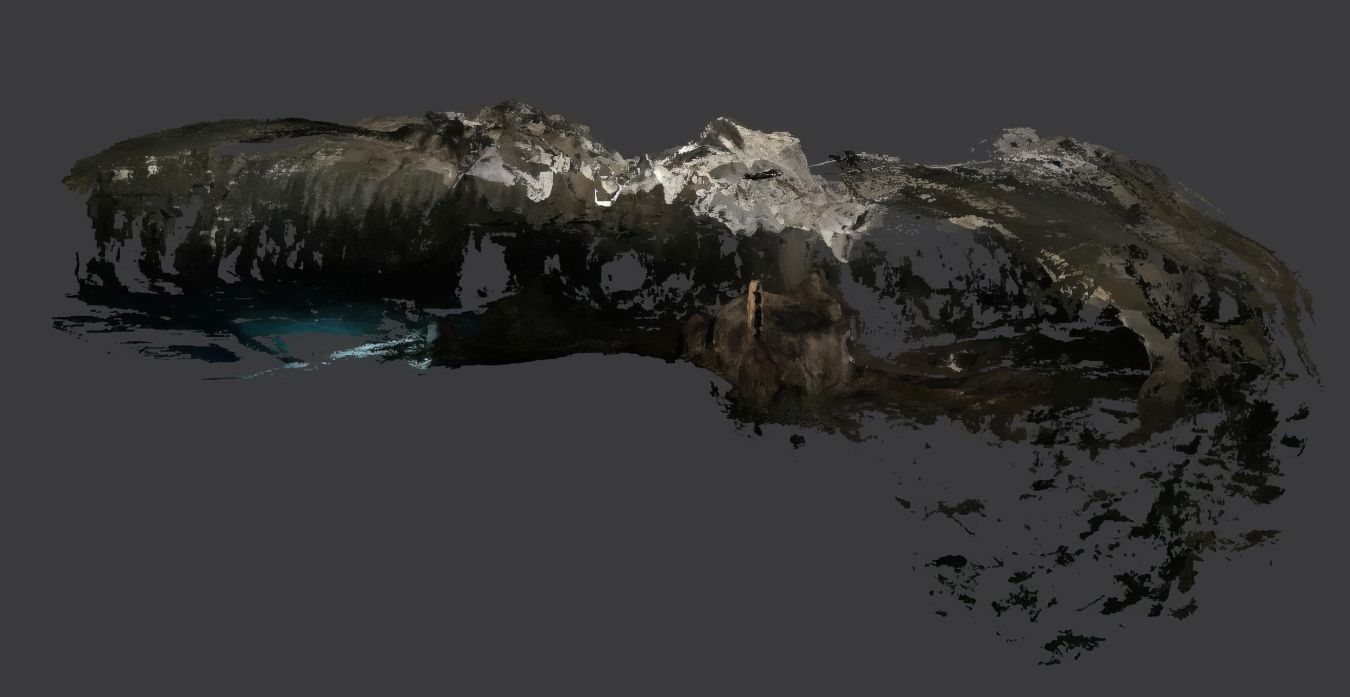

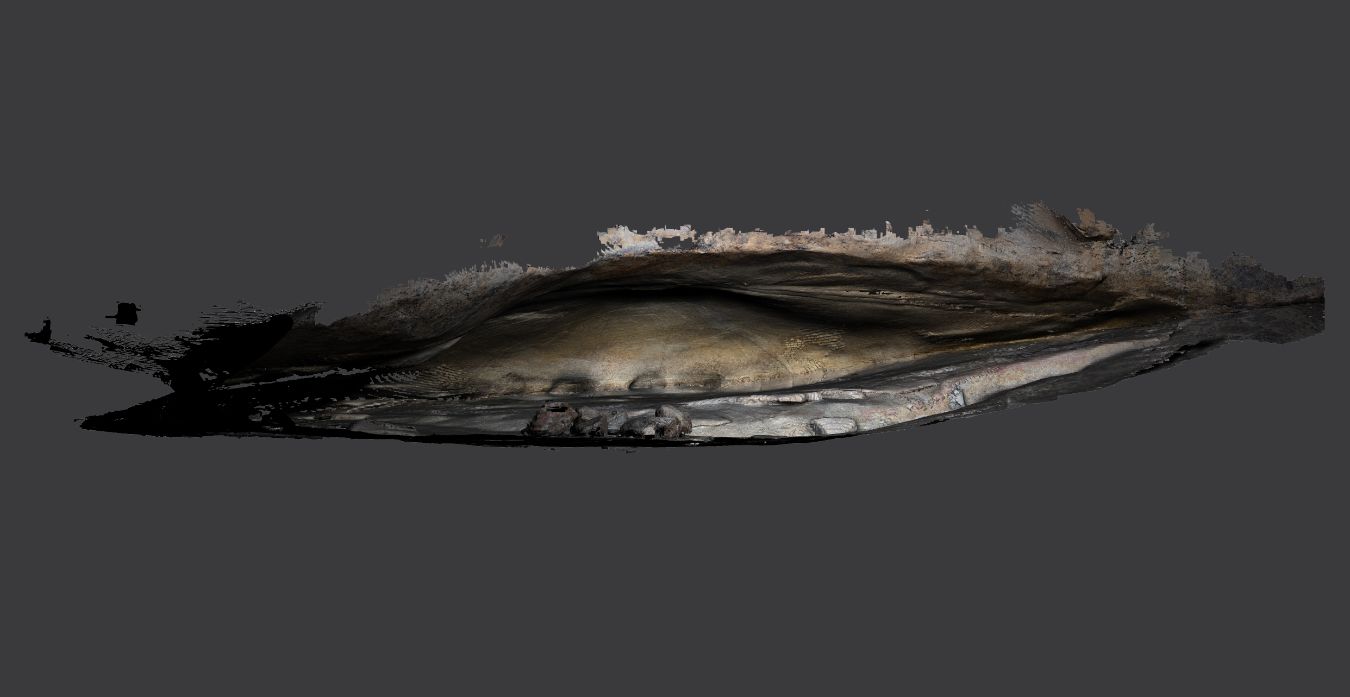

Simultaneously, I was conducting fieldwork in collaboration with artist Charles Stankievech, visiting locations key to speculating about the early formation of the Earth before the emergence of biological life as we know it. Rather than engaging in debates about “intelligence”– a term laden with hierarchical implications – I wanted to center the conversation around “life” itself. My aim was to broaden its definition, reflecting on how even scientific understandings of life continue to morph and expand with new discoveries and deeper insights. This approach allowed me to explore whether we might consider this technology as a form of emergent life, prompting a reexamination of the parameters that constitute life in the first place. As you suggest, this aligns with the ongoing discourse toward a more inclusive definition of life – one that embraces machine, plant, animal, fungal, and opens the space to include other modes of being.

In this sense, “Alter Life” became a way to grapple with these profound shifts – both the emergence of new forms of life and the unsettling transformations they entail.

The prospect of new forms of life emerging raises some uncomfortable questions. It’s not just a question of whether other beings might be friendly to us or want to eat us for dinner, as in the old sci-fi movies about monster robots. The environmental implications might be far more pressing. One way to interpret the narrative of “Buenavista” is that the furry robot is trying to find – or create – a comfortable ecological niche. We now know that organisms don’t just evolve to fit their environments, they also actively shape them. What if the ecological niche of ‘alter life’ is very different from ours?

Ala Roushan

Alter Life wanting, or needing to find its ecological niche is a pressing issue, especially in this fragile state of our environment. Even in these early stages, its altering consequences are taking effect as it consumes immense resources and occupies vast landscapes. From an optimistic lens, we can hope that it’s coming iterations might follow a more sustainable trajectory. For example, that it will embrace possibilities of reducing its power consumption by seeking forms of computing that liberate it from the high energy needs of the cloud. These could include higher efficiency models such as mortal computing offering lower electricity needs and relying on organic substrates capable of regeneration and self-reproduction.

Yet even if these technical adaptations succeed, will its parameters for optimizing the environment for its own needs continue to maintain a habitable biosphere for us? So as Alter Life alters the planet, what we can hope for is that our desires could possibly align. Perhaps its desire to keep temperatures cool, for keeping its servers better functioning (using less energy) and keeping a cool atmosphere for its mortal wetware, align with our need to combat global warming. But can we be so idealistic as to hope for long term co-habitation on this planet? It seems inevitable that our requirements for planetary care versus its technological optimization will soon diverge. With an intelligence that will surpass ours, we must consider that it might prioritize its needs over ours, much like we have prioritized our own existence over other forms of life we perceive as inferior – plants and animals (not mentioning other fellow humans). So, it is not hard to speculate that Alter Life will cultivate the earth towards its own needs – reaching a tipping point when the Earth becomes vastly different from what we require.

The idea that Alter Life might have different needs – for example, for energy sources, cooling conditions, water and minerals – and prioritize them over the needs of humans and other life forms raises some ominous possibilities. Perhaps our needs could align to some degree, for example for a cooler planet. And indeed, some have high hopes that AI will help handle the climate crisis. But there could be methods of achieving the broad goal of climate cooling that would be fine for alter life, but not for many of the people and other creatures on this planet. You’ve been thinking a lot about Solar Radiation Management, a set of experimental techniques under development that could cool the planet by deflecting sunlight. One strategy is to mimic the effects of volcanic eruptions by injecting sulfur dioxide into the upper atmosphere, however the effects on weather systems, acid rain, etc. might be catastrophic in their own right. Does it help to think about these issues from the perspective of another life form?

Ala Roushan

It’s interesting to contextualize the debate of Alter Life within the much-contested concept of solar geoengineering, where it might play a critical role both in simulating environmental models as well as structuring models of governance to regulate its implementation. As you mentioned, we’re referring to strategies of Solar Radiation Management, a terraforming project that conditions the stratosphere by scattering aerosols to mitigate the heat from solar rays, with the objective of creating a cooler planet. The main challenge and source of strong resistance to this strategy rests on two insurmountable obstacles: first, achieving the science for accurate and effective implementation – which includes addressing discrepancies between predictive models and sustainable real-world outcomes; and second, establishing adequate governance – which includes securing a long-term global consensus.

In this context, in a best-case scenario, Alter Life could play a role in addressing some of these critical challenges of science and governance. But in a more likely scenario, we must consider the intensified challenges that compound. For instance, the consensus that we struggle to maintain among humans will become even more complex when factoring in the desires and needs of Alter Life – a life that doesn’t share our biology, our needs, or our temporality. In this case how will the ideal planetary atmosphere be defined? Ideal for who? And so ultimately, can we see cohabitation with Alter Life even possible?

In “Buenavista”, we witness a figure that composing its own corporeal motion in tandem with a more coherent environment. And yet, this environment is one that looks nothing like our real planet – in it, you have ice bergs and cactuses and tides flooding into a desert – a collage of elements that makes sense in digital space but is fundamentally disconnected from this world as it has evolved geologically. Are simulations and modeling practices leading us to imagine that we can manipulate the bio and geosphere as if it were a video game?

Ala Roushan

The ability to model and simulates nature in some ways has brough us closer to comprehending the complexities and vastness of the planetary environment. The fact that we can now create models that encompass the Earth’s entire weather system—processing massive datasets, tracking patterns in real time, and predicting futures – is remarkable. The geoengineering proposals we discussed are only even conceivable through the predictive modeling afforded by our computational machines. But models fail. And the accuracy of the simulation is limited to the limits of these technologies and the parameters that govern them.

Our overreliance on the model to capture the intricacies of the natural world exposes us to biases and blind spots. For example, even with SRM, the question remains if the model can capture the cascading effecting that can arise by intervening in the delicate dynamics of weather. In other words, as we attempt to model and fix one problem what are the domino effect the model fails to predict – possible disruption to regional rainfall, to monsoons, to ocean currents. So, I agree with the contradiction you’ve pointed to: that in simulating nature within the digital realm, we remain fundamentally disconnected.

The model has put us in a god like position – an illusion of the video game – hovering over the planet as though we are in control.

The work “Anima Atman” reveals an uncanny motion of plants, alluding to the limits of human perception of plant life. This raises the question: would we even be able to recognize alter life if it were present in our midst? Could there be something existing already, or evolving, that would expand our idea of life? Conversely, might alter life expand our capacity to recognize existing beings like plants and microorganisms that are at the threshold of human perception, intuitive grasp and empathy?

ALa Roushan

Much like the limitations we discussed in modeling, our capacity to perceive is shaped by the boundaries of our understanding, biases and blind spots. This is especially true when it comes to defining life, and more so when attempting to recognize forms of life unlike our own. In the book “The Desert Turned to Glass”, I wrote of emergence considering that the development of AI is evolving toward autonomy in its potential to generate independent subgoals and so exceed its programming. The result is a computational system untethered from human intention: marking its pivotal shift from instrument to agent. As such a being will emerge whose decisions, desires, and direction may unfold entirely outside of the human.

But here is where our fascination and fears lie: will its existence be so far beyond our comprehension that we fail to even recognize it altogether? Might it elude our perception – not because it hides, but because we lack the cognitive framework to see it as alive and recognize its existence? Just as the full dimensions of human consciousness remain elusive even to ourselves, this emergent life might also exist within a field of the unknowable. In fact, it may even invert the question of consciousness entirely. A reversal might occur: who is conscious of whom? And to what degree?