Pearls in art. From Botticelli to Comilang

12/26/2025

5 min reading time

Art history has for centuries distributed pearls and beads without particularly scrutinizing whether they were understood. It has hung them from earlobes, braided them into hair, thrown them onto tables, sunk them in the oceans, and brought them back to the surface again. Pearls have been worn, hoarded, sacrificed, admired. Never innocent, rarely coincidental.

1

Sandro Botticelli

“The Birth of Venus” (approx. 1484)

Before pearls became jewelry they served as myth. Venus rises out of the shell as if she were herself an outsize pearl. Everything here is origin: Sea, body, surface. Here, the pearl is not an object, but an idea, born from abrasion, water, and patience.

2

Hans Holbein the Younger

“Portrait of Anne Boleyn” (1534–35)

A pearl necklace with a single letter suffices to make a political statement. The “B” is close to her neck, the pearls gleam loyally where loyalty has long since become brittle. Jewelry as a demonstration of power, pearls as the argument.

3

Johannes Vermeer

“Girl with a Pearl Earring” (approx. 1665)

One ear, one glance, a drop of light. Here, the pearl is larger than need be, perhaps larger than possible. It reflects everything and reveals nothing. What remains is projection. Who is looking at whom – and why for so long?

4

Rosalba Carriera

“Portrait of a Woman with Mask” (approx. 1720)

Pastels, close up, seduction. Carriera painted pearls not as opulent glory but as an obvious matter. They are part and parcel of the game of surfaces, of self-orchestration, of masquerade. Here, pearls are less status than strategy.

5

Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun

“Marie Antoinette” (1786)

The queen wears pearls like a sedative. Soft, bright, as harmless as possible. Vigée-Lebrun tries to generate closeness where distance prevails. The pearl is meant to offer a human touch – and fails utterly, historically.

6

Édouard Manet

“Still Life with Flowers, Fan, and Pearls” (approx. 1860)

The pearls are dropped on the table. No body, no neck, no stories that they convey. Manet strips them of any aura and renders them as things among things. Transience added into the bargain.

7

Gustav Klimt

“Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I” (1907)

Gold, surface, ornament. Here, the pearl as good as disappears in the pattern, becomes part of a system of gleaming luster and glances. There is no dividing jewelry and body any longer, all is surface, everything infused with meaning.

8

Maria Nepomuceno

“Magmatic” (2013)

Pearls with no function as jewelry. Yoni shapes, ceramics, strings, body fragments. Nepomuceno construes pearls as material, as memory, as an organic principle. Here, jewelry becomes sculptural, political, open.

9

Zanele Muholi

“The Sails, Durban” (2019)

In her image shot in “The Sails, Durban”, Muholi consciously makes use of pearls as a pictorial element within a photographic self-portrait. The piece is part of their series “Somnyama Ngonyama” (Hail the Dark Lioness) in which Muholi explores issues of self-representation. The pearls function less as a decorative detail and more as a reference to historical conventions of pictorial representation on which photography clearly draws. In this way, the image highlights how visibility is created, read, and controlled.

10

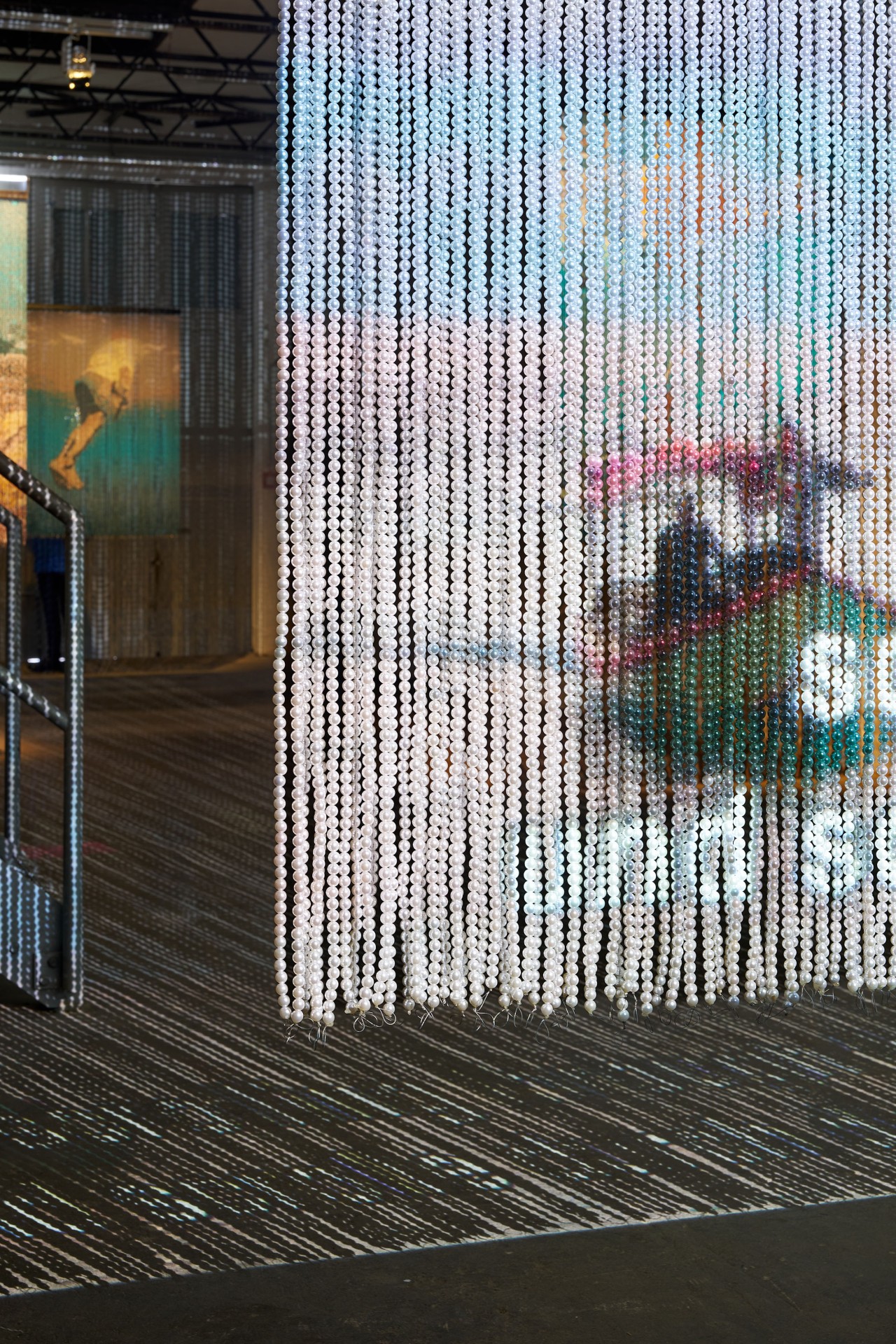

Stephanie Comilang

“Search for Life II” (2025)

For Stephanie Comilang, the focus is on the circulation of the pearls – and with them the paths, people, and stories to which they are tied. In “Search for Life II”, Comilang traces the economic, historical, and personal concatenations that have arisen around pearls: Trade routes, currencies, postcolonial dependencies, and personal biographies.

In her film-based installation, Comilang focuses on those who work within these structures, who migrate, and their concerns, meaning those whose stories were for so many years hardly associated with the glory and gleam of pearls in art history.

Thus, in Comilang’s piece the pearl is not stripped of its magic, and instead contextualized. It functions as the interface between global trade and personal experience. The jewelry loses none of its value.

In this way, the pearl becomes an archive of contemporary life: fragile, recalcitrant, a repository of experience. And suddenly the old jewelry no longer seems something from a world long past, but astonishingly topical. Perhaps art history never distributed its pearls wrongly. Perhaps it has always known: A glorious gleam arises not from purity, but from abrasion, from rubbing things the wrong way.