“Real Utopia” in Bockenheim

08/13/2025

11 min reading time

What will the new SCHIRN in Bockenheim look like inside? Together with the architecture collective raumlabor the SCHIRN developed the concept and design for the entrance into the industrial building. An interview with SCHIRN curator Martina Weinhart and Markus Bader from raumlabor gives insights into the work process behind the scenes.

The SCHIRN has collaborated with raumlabor quite a few times. Many of our visitors already know you, for example through the exhibition architecture you created for “Plastic World.” Could you briefly outline what makes the collective so special?

MArkus Bader

Gladly. We set up shop back in 1999, which means 25-plus-one years now. Essentially, we are a group of nine architects, but in total anywhere between 15 and 25 people take part. We still thrive on our first or “founding” idea, if you like – namely to do “non-disciplinary architecture.” The intention is to think about urban planning differently: We concern ourselves with the overall context of a place and in that way aim to overcome the role of the architect as someone who simply designs a space.

We call our projects “real utopias” or “micro utopias,” by which we mean places that actually realize future visions now – and not just in theory but also at the level of action. In the process, we concern ourselves with topics that get discussed in the context of the responsibility architecture has in relation to climate change. It’s clear to us that we cannot use materials at will but must always be conscious of sparing resources. What’s available? Who’s on location? With which actors do we need to connect in order to explore such a future together? And the social and political components always need to be considered, too. This approach stems more from anthropology than from classical architecture, with the idea being to “carefully nurture the dynamics of the place.” It is therefore precisely not about pure design, but about developing a social fabric. That also plays a key role in our scenographies and architectures, where we focus on places of interaction and discovery, places where people come together. This approach has always been part of our philosophy.

That’s why we thought a project like redesigning the Dondorf Druckerei fitted perfectly. In the development and realization of the new location as an exhibition venue, one key idea was crucial to us from the outset: This historical building must become a place of encounters. It is embedded in a vibrant district of town, and we want to interact with that. It’s a large project for which we are working with a large number of players. We contacted you specifically with a view to structural considerations, and above all for the design of the ground floor. And we then discussed two concepts during the concept phase: the “Collage Principle” and “SCHIRN Active.” Could you flesh that out a bit, perhaps?

markus Bader

The Dondorf Druckerei is a former printing building, and we are aiming to discover the building anew and breathe new life into it. When it came to the ground floor, we therefore quickly expanded our thinking: The whole floor needs to open out to the city and connect in order to create a harmonious whole.

The “Collage Principle” refers to the past ways in which the Dondorf Druckerei was used. On the grounds, there are various rooms and elements from different construction periods and with different functions. For example, the main building also has an annex with the now second exhibition hall, in between there are workshops and a yard. We do not want to completely write over the existing spaces, but instead to respect what is there and highlight it so that a multifaceted picture emerges.

On top of this, we know that conditions may change during the construction phase. It is a dynamic setting, meaning we need to respond repeatedly to new insights, and in this way a kind of collage will arise.

The other central aspect of the redesign is that we as the SCHIRN want to make the place accessible to a broader public. It must be possible to use it for our many SCHIRN program formats, to meet the needs of all sorts of visitor groups, and also for visits without a paywall. It must be possible to visit exhibitions but also to use the rooms differently, too.

markus Bader

This is exactly how we understand the term “SCHIRN Active” as regards the design of the SCHIRN as a space where different activities can take place, and which then reflects the diversity of the public realm. For example, the foyer is not meant to have the feel of a closed-off room in an institution space but should be a place where local people can spend time, meet others, or work. Essentially, the idea is for museum/institutional practices to mingle with other public practices – simply one big invitation to the neighborhood, to everyone interested, to connect with this place and together infuse it with life. Initially, the opinion prevailed that the Dondorf Druckerei only had one clear frontage, but after we had taken a closer look at the various subway exits and the entire vicinity, we swiftly realized that there are many different paths that lead to the Dondorf Druckerei. We therefore repurposed all its sides as frontage and are inserting two niches into the yard’s outer wall. In future, there’ll be a friendly welcome awaiting you on all sides.

Let’s go through the building together in our minds. What can I expect when I arrive at the new main entrance? Visitors move through the foyer and then continue on to the yard – what is the idea behind that sequence?

Markus Bader

A curved ramp leads up to the main entrance, and you arrive at a kind of porch canopy, meaning a small portal made of surprising different materials such as a tubular steel system, a metal grille, and corrugated plastic panels. These can be used in various different ways: as a display system, as a raised dais for speakers, as a space for an artwork, or as a news transmitter to present a poster or a banner.

On entering the foyer, on the left there’s an area for workshops or events; on the right, you have the MINISCHIRN. Straight ahead, the service and info counter is in a centrally installed block, and here colored and geometric elements that already occur at the portal pop up again. You can pass by the counter on the right or left: On the left, you reach the café; on the right of the info cube, you step through the door into the courtyard. Here you’ll encounter a similar canopy to that at the entrance, but in this case the area serves as a patio for the café.

In other words, on the ground floor we have exactly the kind of open space we wanted to create, with different areas where you can spend time, and different usages.

markus Bader

Exactly, the ground floor is intended to be open and also to offer peace-and-quiet spaces. The workshop zone, for example, and the info desk have roller shutters. When these are up, you automatically have a large space, so the entrance area morphs into a hall, allowing you to experience the basic structure of the building. If they are closed, you have a dedicated workshop zone. This means the use can constantly be re-engineered and repurposed. Unlike in the two exhibition halls, on the ground floor various different usages coexist.

When modernizing and designing the building, we wanted, as you said, to work with the existing structures. Could you tell us a bit about how the existing architecture was treated, and about the materials and the color concept we developed together?

markus bader

Since it is a commercial property, there is constantly the potential for surprises during the modernization work. For example, when we removed a suspended ceiling on the ground floor, we suddenly found ourselves staring at an incredibly huge, extensive load-bearing structure made of gigantic steel girders. No one had expected that, so we hadn’t devoted any thought to dealing with the huge girders.

Plus the pillars we discovered – they were quite a surprise, too.

markus bader

Exactly, beautiful old cast-iron pillars were hidden away in the walls, in part flanked by more recent additional pillars needed to bear the immense loads. Such discoveries were something we construed as an opportunity, and we tried to integrate them into the design. I’m really excited about the floor – it’s mastic concrete. We’ve repaired it, and its marvelous multifaceted pattern is now visible, documenting the period it represents. The same is true of the cap ceilings. All in all, you can really feel the multifarious aspects of the original architecture: If you look up, you’ll see the open cap ceilings, the ventilation, the cable ducts running between them, and the existing steel girders. Then there are the walls: They were all rendered, painted, and created for a normal office atmosphere, in part with built-in furniture and cupboards. During construction, we had to remove the render to address necessary hazardous material remediation, meaning the walls suddenly stood there naked, just the brick. We then asked ourselves whether this would now be how we left it. We decided we wanted to give the ground floor walls a lick of white so that not every brick is visible individually and the dark color of the bricks did not dominate the rooms.

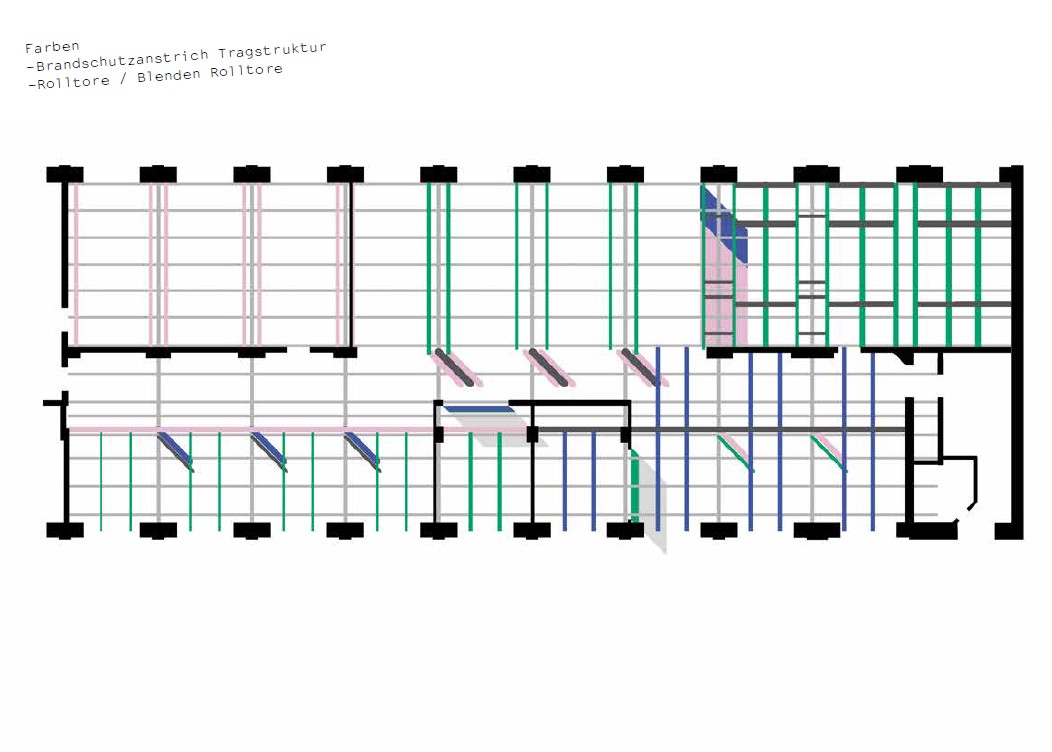

That was, as it were, the basis on which we developed the color concept, whereby we did consider giving some existing elements a specific new color.

markus Bader

The partly bright colors we chose (green, yellow, blue, and pink) represent the various new usages and are meant to become part of the existing spaces so that the architecture has a fresh feel to it. Added to this, the steel girders had to be painted in order to protect them against corrosion, and they needed a fire-protection coat, too. We opted for a colorful coat. You first encounter this combination of color and materials in the entrance portal.

You just mentioned built-in furniture. What will the future fit-out on the ground floor be? We’ll be using materials that reference site-specific conditions, won’t we?

markus Bader

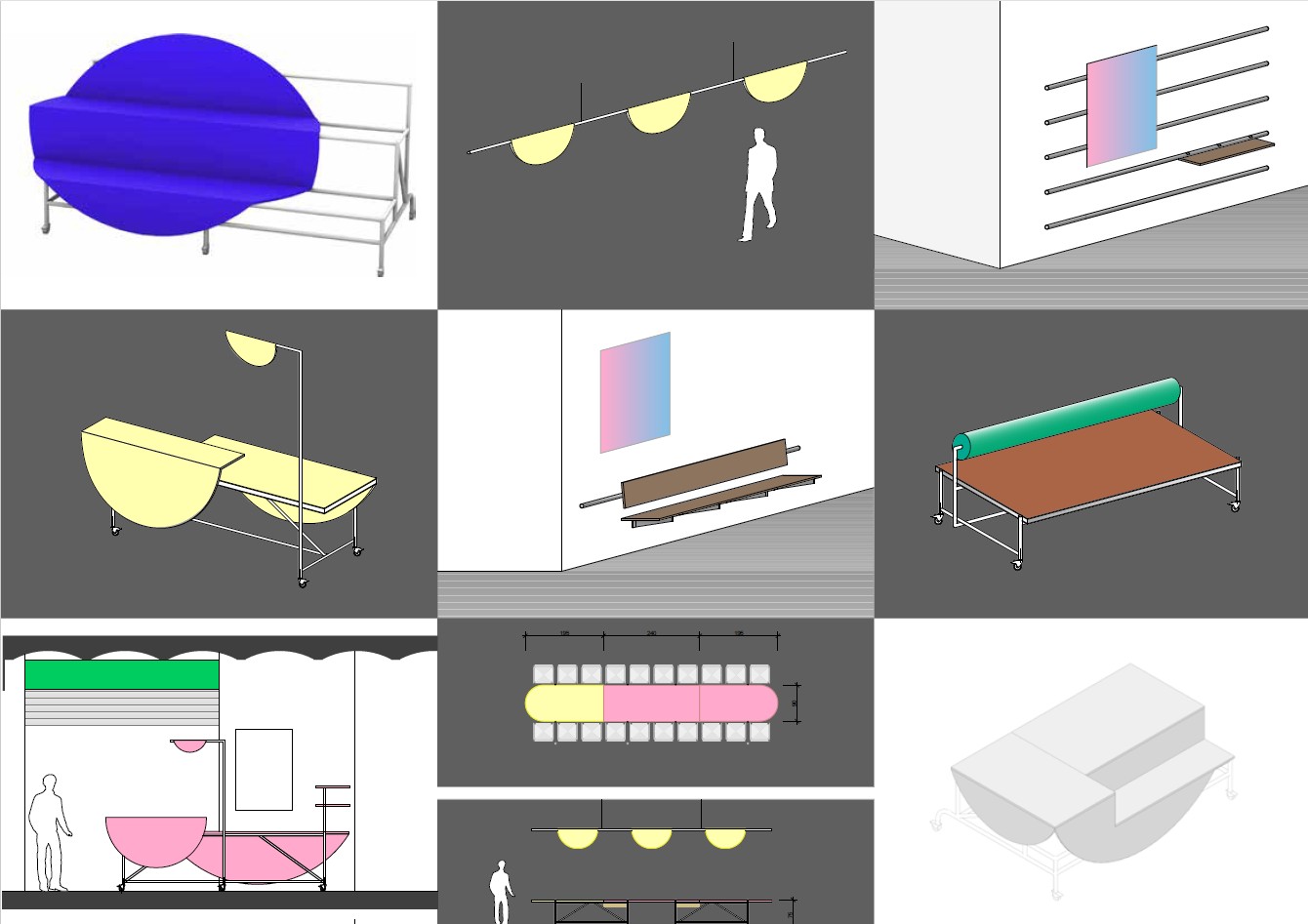

We’ve designed a special small furniture collection, meaning seats and a large table. What’s special is that the furniture cannot be immediately recognized as such, other than the table, that is. For example, there’s seating that is much too large to be a sofa and doesn’t look like one either. Yet it encourages you to sit down on it. There will be all kinds of furniture, from table seats to a small podium. We’ll be making them from tubular steel, pipe connectors, wood, and some soft materials – and thus referencing the space’s industrial character. They are also very easy to make, and after their temporary deployment in the Dondorf Druckerei they can simply be taken apart again. New things can then be made from the individual elements that make up the furniture.

Markus, thanks so much for your time. I’ve very much enjoyed our successful collaboration on this great project; we’ve gone into even the most minute details in an effort to jointly realize our idea of sustainability, participation, and openness in the design of the new SCHIRN space.

markus Bader

Thank you.