Dada in 10 (F)Acts

09/15/2025

7 min reading time

Dadaism is considered one of the most progressive and controversial art movements of the early 20th century. Read on for 10 exciting facts and background information about the Dada movement.

Lorem Ipsum

Dada what? Emerging as a reaction to the First World War, Dadaists rejected all established conventions in art, literature and social order. Instead, they celebrated unpredictability, absurdity, and provocation, experimenting with new forms of expression. Read on for 10 exciting facts and background information about the Dada movement.

1

The Birth of Dadaism

From 1914 to 1918, the First World War raged across Europe. Many artists, writers and intellectuals fled to neutral Switzerland, seeking places and communities where they could exchange ideas and engage in creative, interdisciplinary resistance against war, social order and conventional art. The Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich, founded on 5 February 1916 by Hugo Ball and Emmy Hennings, served as their central meeting place and is considered the birthplace of Dadaism. The Cabaret Voltaire offered an open stage for various avant-garde art forms: Ball recited sound poems dressed as a bishop, Sophie Taeuber-Arp performed as an expressive dancer, Marcel Janco displayed his masks and recited so-called simultaneous poems together with Tristan Tzara and Richard Huelsenbeck. The Cabaret Voltaire also hosted exhibitions featuring works by international artists who sympathized with the movement, such as Arthur Segal and Pablo Picasso.

2

Dada Where?

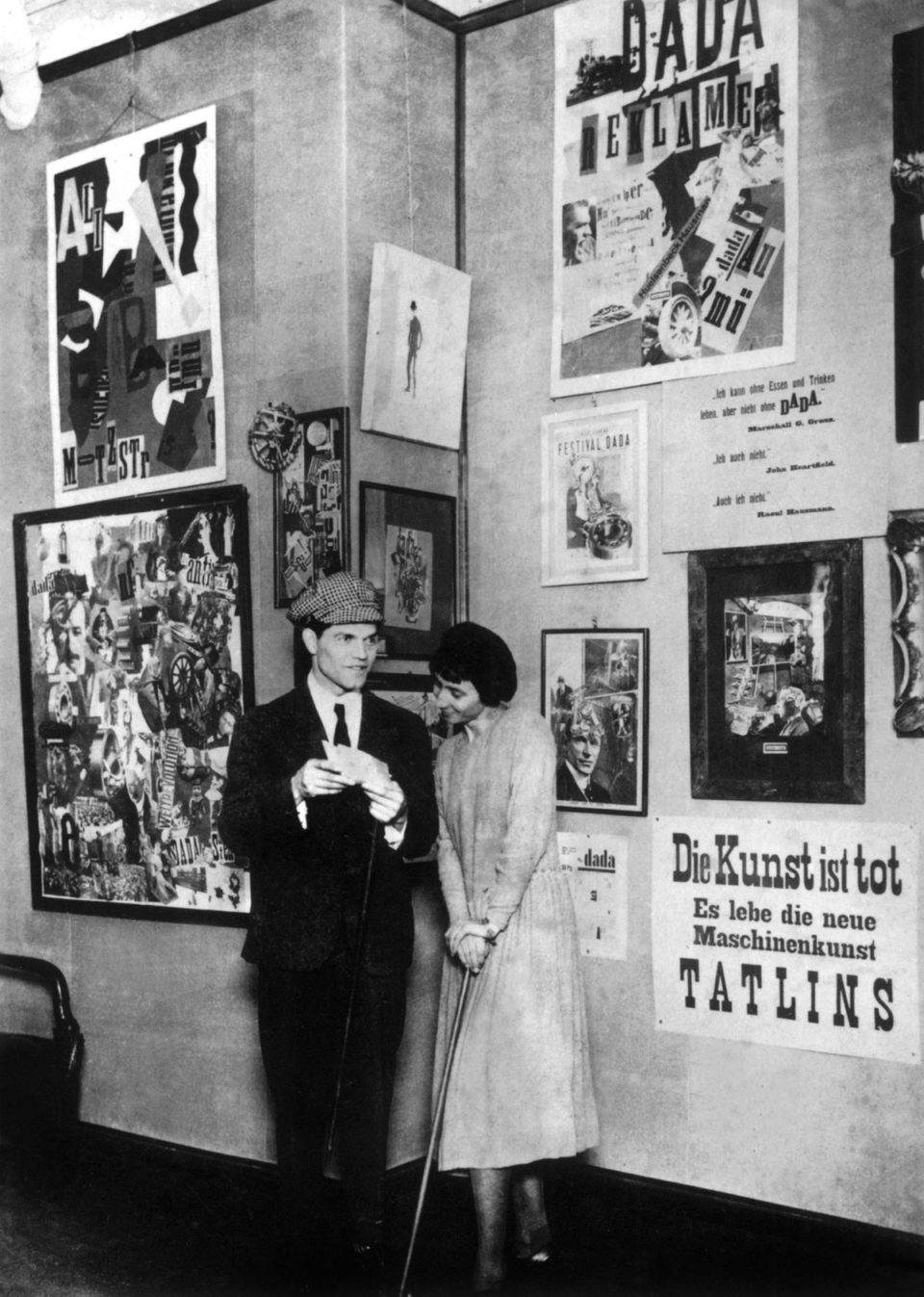

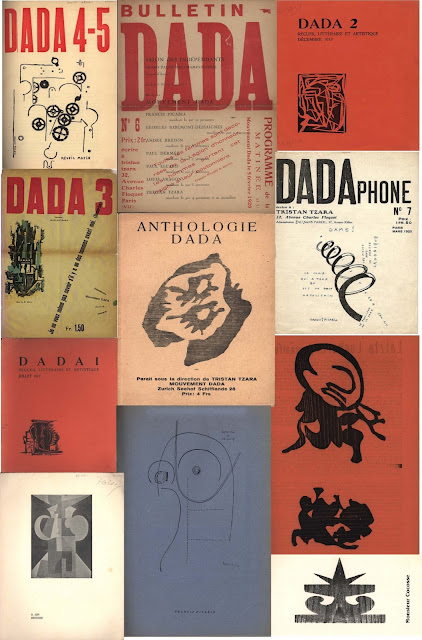

Alongside its official establishment in Zurich, Dada movements also emerged in Berlin, Paris and New York. The artists kept in close contact, travelling between these locations to develop joint performances and loan works for exhibitions. One of the most important ways in which Dadaist ideas circulated internationally was through their journals, which were exchanged, quoted and displayed at exhibitions. This created a dense network that established Dada as an international movement.

3

Dada Who?

Dada had many faces: Hugo Ball, Emmy Hennings and Tristan Tzara met in Zurich, and their ideas were later given a political edge in Berlin by Raoul Hausmann and Hannah Höch. Meanwhile, in New York, Francis Picabia and Marcel Duchamp were experimenting with objects. The latter made his mark on art history with his famous readymades. In Paris, Man Ray explored film and photography and met artists such as Tristan Tzara, Sophie Taeuber-Arp and Suzanne Duchamp. They participated in lively, extravagant soirées and helped to propel the movement forward. Many of these artists are still well known today, even beyond their Dadaist work.

4

The Language of Nonsense

“jolifanto bambla ô falli bambla / grossiga m’pfa habla horem / égiga goramen” was written by Hugo Ball in 1917 in his sound poem “Karawane.” For the Dadaists, language was an artistic tool, whether spoken or written. The aim of these language games was to break down the connection between words and meaning, bringing sound and poetry to the fore. In collages or on posters, numbers and letters became graphic design elements through unusual arrangements, different font sizes and colors, or flowing lines. In addition, the Dadaist approach to language also had a political dimension: by fundamentally questioning its logic, they simultaneously exposed its potential for manipulation, which manifested itself during the First World War in the form of propaganda and empty political promises.

5

Female Artists of Dadaism

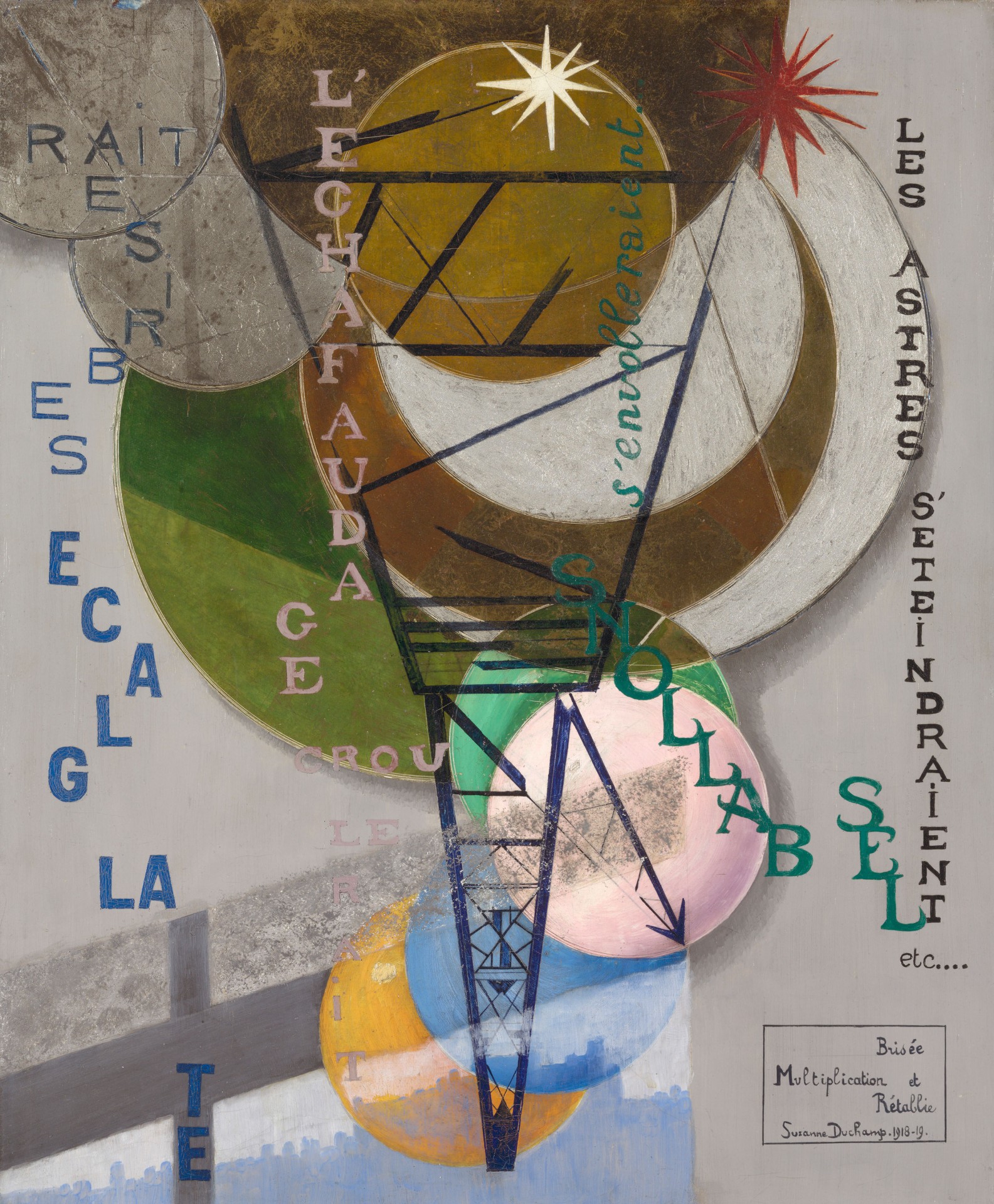

Given Dada’s anarchic nature, it is not surprising that its approach to gender norms differed from that of other avant-garde movements, which were often dominated by established male networks and in which women took a back seat. In Dadaism, however, women were visible from the very beginning! Emmy Hennings, for example, founded the Cabaret Voltaire together with Hugo Ball; Sophie Taeuber-Arp brought embroidery and textile art to the movement, and Suzanne Duchamp developed her own unique language of images and text alongside her brother Marcel.

6

Machines in the Mind

The early 20th century was marked by technical achievements that had far-reaching consequences for society, politics, and the economy. The assembly line drove mass production, changing consumer habits in the process. Cars and airplanes accelerated transportation, and electricity reached both industry and private households. While the Futurists enthusiastically embraced this progress, the artists of Dadaism reacted with skepticism. As warfare became more industrialized, people began to feel alienated; they felt like small, interchangeable parts in a large industrial machine. Technical elements such as gears and circuit diagrams therefore appeared increasingly frequently in the Dadaists’ works—as a critical commentary on the advancing technologization, which in the Dadaists’ belief, had made war possible in the first place.

7

Dada and Collage

The forms of expression are as free as Dada’s anarchic nature. The collage, in particular, underwent a radical transformation at the hands of the Dadaists. Armed with scissors, glue, and cut-out pictures, the artists set to work. One of the most prominent artists in this genre is Hannah Höch. In her now iconic work “Cut with a Kitchen Knife,” humans, animals, technical elements, and writing are brought together, all cut out from magazines, newspapers, or photographs. The protagonists represented include politicians, scientists, and Höch’s fellow artists: She places a bowler hat on Kaiser Wilhelm II, plays with proportions, and repeatedly challenges gender stereotypes, for example by placing George Grosz’s head on the body of a ballerina.

By combining different cut-outs, the Dadaists created new meanings from familiar motifs, challenging supposed truths, and democratizing the artistic process in a playful way.

8

Dada haha!

At first glance, it may seem surprising that such an absurdly comical movement as Dadaism emerged during a period marked by war and social tensions. And yet, the works of the Dadaists are permeated with humor in many forms: Wild performances were accompanied by loud clapping and cheering, Dadaist poems are full of puns, and many of those caricatured may well have felt they were being mocked. At the same time, humor was deliberately used as a cutting political weapon. It served as a means of criticism and resistance, poking fun at bourgeois convictions that were considered meaningless.

9

Publication & Manifesto Culture

The Dadaists not only used daily newspapers, magazines, individual snippets and dozens of reproduced photographs in their collages. They also became involved in their production process: Francis Picabia published the international magazine “391”, Tristan Tzara was editor of the bulletin “Dada”, and leaflets and manifestos expressing the ideas and goals of the movement were circulated on various occasions. These publications were one of the most important ways in which Dadaist ideas circulated internationally. They also provided another platform for the artists to express their creativity, with room for typographical experiments and a mixture of words and images.

10

The Legacy of Dada

The ideas of the Dadaists evolved over time, eventually leading to the creation of new art movements that would go on to become historic, including Surrealism, Pop Art, Performance Art and Conceptual Art. Many of the early Dada artists later went their own ways independently of the Dada collective: Max Ernst created dreamlike surrealist worlds, Georg Grosz became one of the most important representatives of New Objectivity, and Suzanne Duchamp continuously explored the tension between painting and poetry in her work. The legacy of Dada is the rejection of all kinds of conventions in art and life, a characteristic that still shapes the work of many artists today.