Now at the SCHIRN: Suzanne Duchamp. Retrospective

09/23/2025

9 min reading time

From October 10, the SCHIRN presents a comprehensive solo exhibition of the highly individual pictorial language, originality, and subtle sense of humor of Dada pioneer Suzanne Duchamp.

Lorem Ipsum

From October 10, 2025, to January 11, 2026, the SCHIRN is presenting the world’s first comprehensive solo exhibition dedicated to a pioneer of the Dada movement, Suzanne Duchamp (1889–1963) in cooperation with the Kunsthaus Zürich. The retrospective shows the multifaceted oeuvre of an artist whose work extended over a period of fifty years and who contributed to the development of Dadaism during the 1910s and early ’20s. Although Duchamp’s works are represented in world-famous collections, and she had strong connections to major art world figures during her lifetime, her artistic significance has long been overshadowed by her brothers Marcel Duchamp, Raymond Duchamp-Villon, and Jacques Villon, as well as by her husband, Jean Crotti.

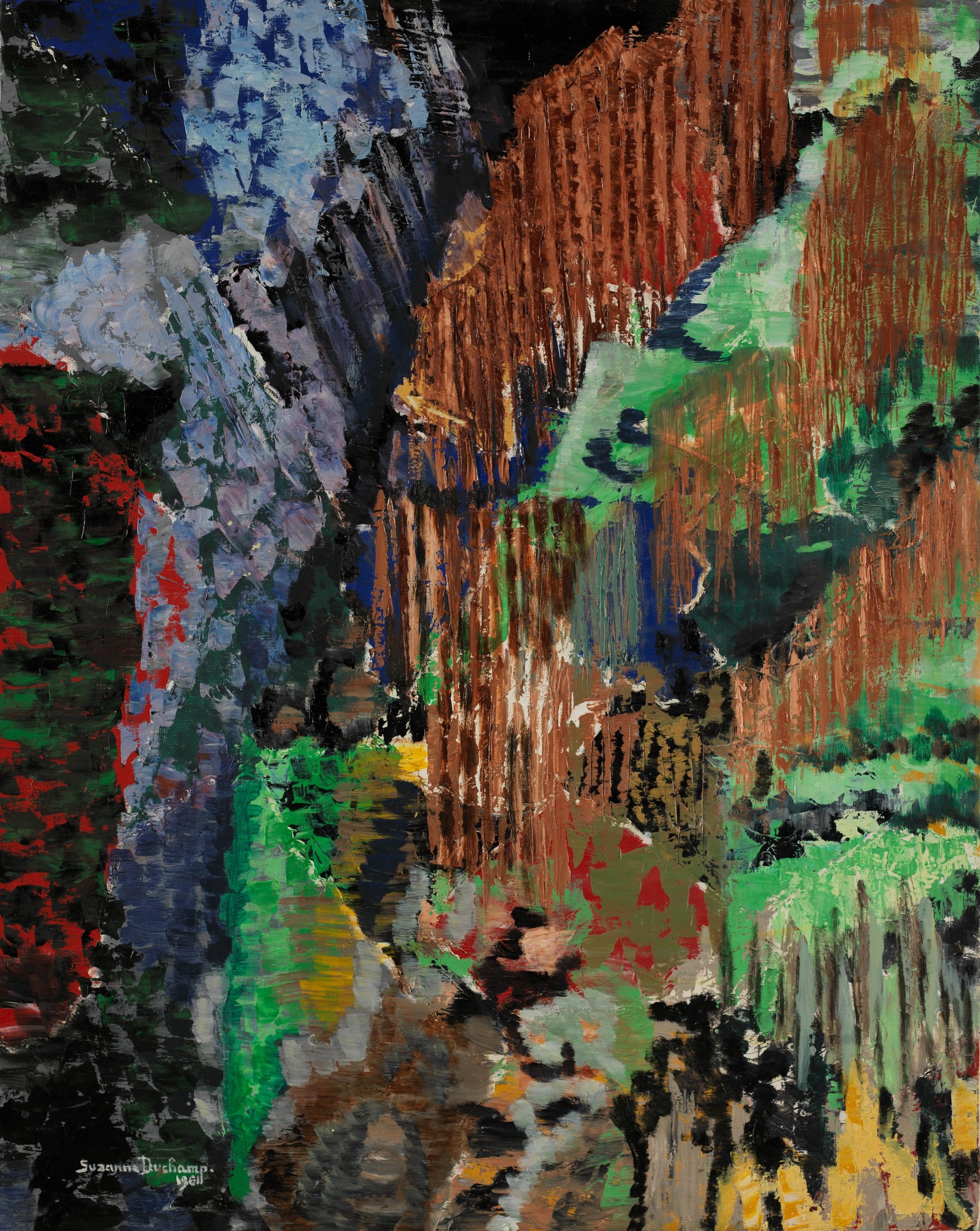

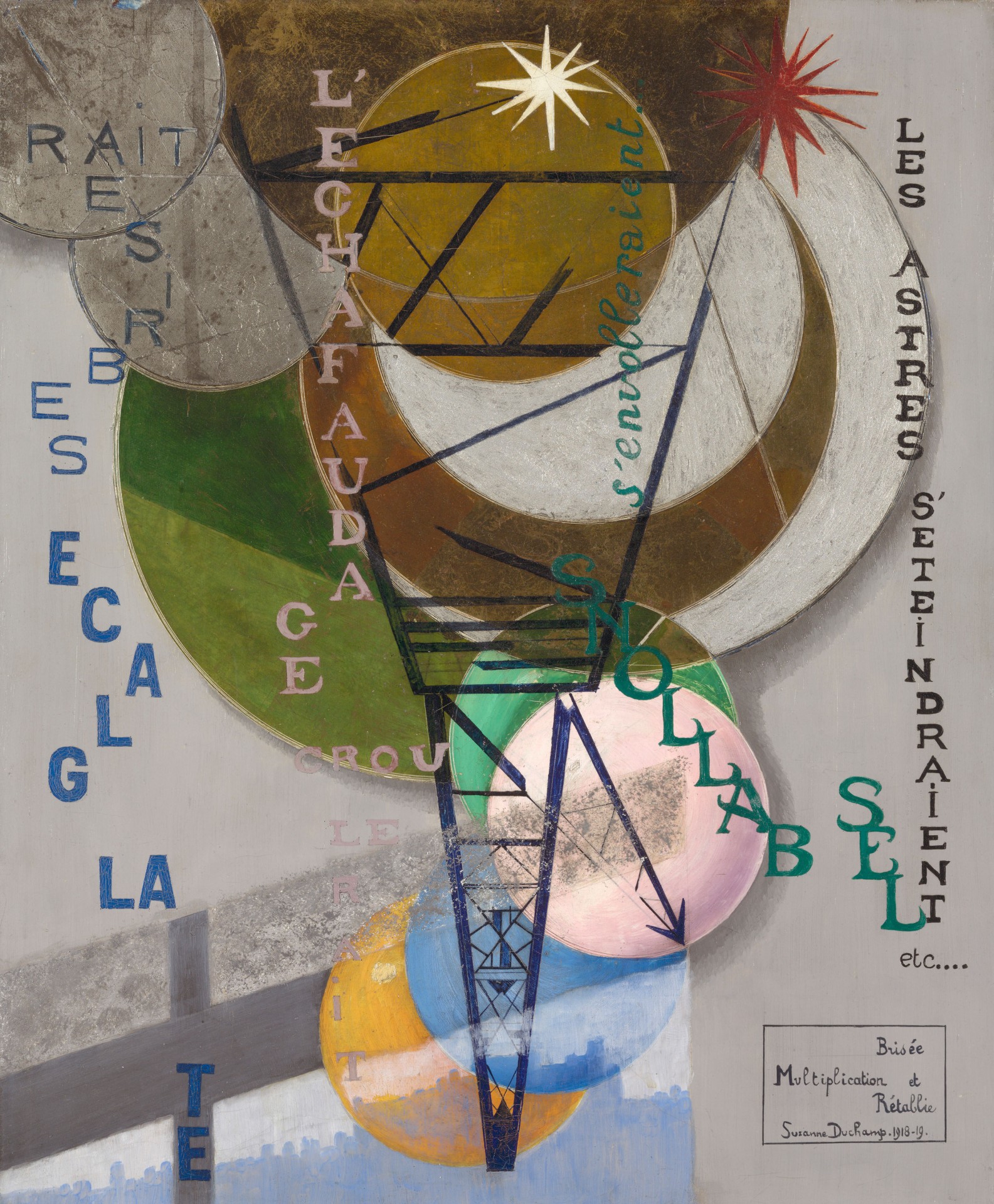

The retrospective contains around eighty works, some of which were rediscovered during the extensive research for the exhibition, and includes experimental collages, figurative representations, abstract paintings, photographs, and prints, as well as findings from the archives. Together, the works illustrate Duchamp’s artistic independence and freedom. The exhibition particularly focuses on her innovative treatment of materials and media, but also on her broad artistic range, which often defies art-historical categories. Humor and an air of mystery lend Duchamp’s art its characteristic voice. By the mid-1910s, she had developed a subtle pictorial language that was unique within the Dada movement for its combination of the readymade, poetic inscriptions, and geometric forms. In addition to her Dada works, the exhibition illuminates Duchamp’s early Cubist interiors and urban landscapes, and figurative paintings with frequent ironic undertones, as well as landscapes of the 1930s and ’40s and her late works, which return to abstraction.

Early Work and Beginnings in the Avant-Garde

From 1911, Suzanne Duchamp’s work appeared for the first time in prestigious exhibitions in Paris. She incorporated elements of Cubism into her early paintings, a movement she was familiar with through her older brothers Jacques Villon and Raymond Duchamp-Villon. Through weekly meetings in their studio apartments in Puteaux near Paris (now La Défense), the Cubist Puteaux Group was formed. The subjects of Suzanne Duchamp’s paintings during this phase range from portraits and domestic interiors to urban landscapes.

The first work that Duchamp exhibited in modern art circles was a portrait of Jacques Villon (“Portrait de Jacques Villon,” 1910), which shows him painting a self-portrait. Multiple perspectives and fragmentation are found in the painting “Jeune fille au chien” (Young Girl with a Dog, 1912), depicting the artist’s sister with her dog; the work is considered to be Duchamp’s most important contribution to Cubism in Paris. In “Construction” (1913), Duchamp abstracts what is probably the industrial town of Puteaux. The artist’s layering of horizontal and vertical lines and surfaces forms a “subtle” Cubism, capturing the modern character of the urban landscape.

An Independent Artist

The year 1922 represented a turning point in the art of Suzanne Duchamp: After her successful Dadaist phase, she returned to figurative painting—now, however, in a humorous and caricatural way. This period also marked her return to independent artistic work and is characterized by a dynamic use of color. She freed herself from fixed movements like Dadaism and Cubism, and after 1923 exhibited her works less frequently alongside her husband Jean Crotti. Instead, they were shown in group exhibitions with artists like Marie Laurencin, who also explored new forms of figuration. The SCHIRN will be showing the principal work “La Noce” (The Wedding, 1924). With its palette of bright red and subdued shades of gray, Duchamp’s painting is an ironic study of a wedding that questions the institution of marriage as a bourgeois convention.

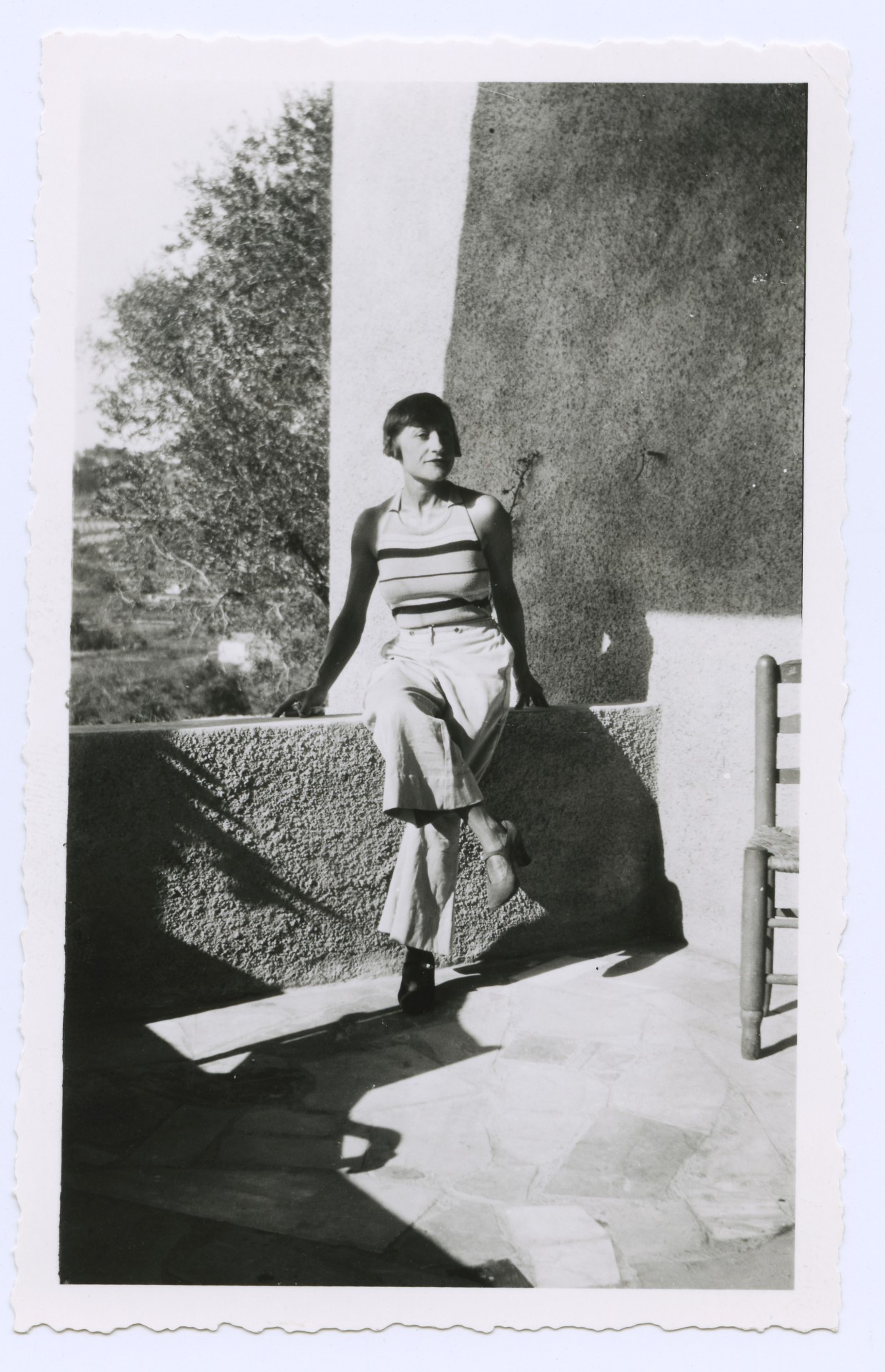

From the mid-1920s and into the ’30s, Suzanne Duchamp worked in Paris and on the French Riviera and earned increasing international attention. The close cooperation with the American artist and collector Katherine Dreier led to exhibitions in New York, including a solo exhibition of her watercolors in 1933. She also exhibited in galleries in Paris and in international group exhibitions. A wide range of subjects can be observed in her works during these years: portraits, landscapes, beach scenes, still lifes, and unconventional scenes of everyday life. In her paintings, Duchamp repeatedly combined these subjects in new configurations. She worked mainly in oil and watercolor and used drawings to plan her compositions. This resulted in eye-catching works like the quirky interpretation of the Garden of Eden, “Le Paradis terrestre” (The Earthly Paradise, 1924), and the unusually direct and dynamic portrait “Lorenzo Picabia” (c. 1927), depicting the son of her friends Francis Picabia and Germaine Everling; Lorenzo who became a recurring subject in her pictorial world.