November 1918, Berlin. The Weimar Republic, a parliamentary democracy, is proclaimed. Initially the 1920s were a period of tremendous revival and social upheaval: a time when women could vote for the first time, when industrialization caused millions to migrate to the cities, and a new class, the class of salaried employees, developed. In the cinema or through novelettes it was possible to reach huge target audiences, and people began to act democratically.

Nevertheless, a freeze on construction imposed between 1914 and 1923 in the cities led to a serious housing shortage. Homelessness and high unemployment figures became the negative defining feature of the masses, which took shape as a working proletariat at the conveyor belt or as a protesting crowd. The faces of the masses are portrayed, for example, in Fritz Lang’s most popular film Metropolis, which reached cinemas in 1927 and was rereleased in a restored version a few years ago.

Yoga in the Weimar Republic

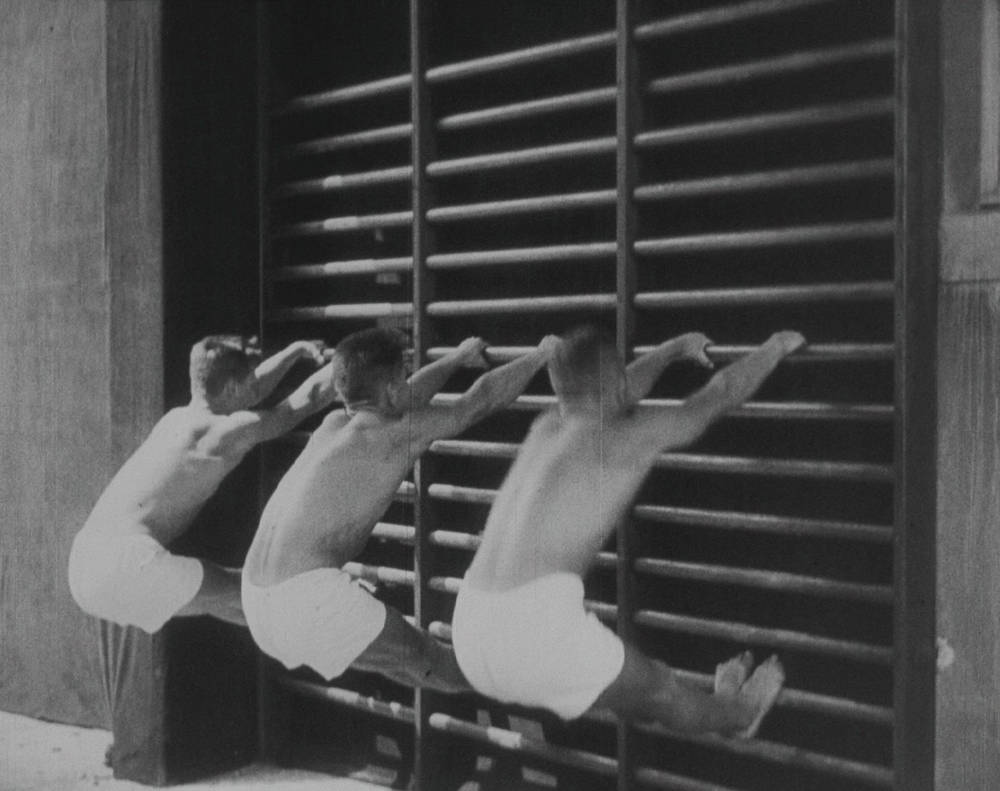

The vacuum caused by World War I, the crises of identity, and the social dynamics ultimately shifted the main focus onto the individual. Hence the individual enjoyed particular popularity in the Weimar Republic, and numerous guides became established for sport and body culture. These propagated ideals, offered cosmetic tips and, thanks to the Japanese fashions of the 1920s, even brought the first yoga exercises to Germany.

Metropolis. Fritz Lang, 1927

Through sport, traditional class models and their restrictions were superseded by a companionable “we” – in 1926 more than four million people gathered in sports clubs. The physical exercise was supposed to form a new type of human being. On the one hand this orientation towards the “naturally pure” body formed the first bridge to the “blood and soil” ideology of the Nazis, whilst on the other it aimed to strengthen the ailing society.

Dancing hands in the factory

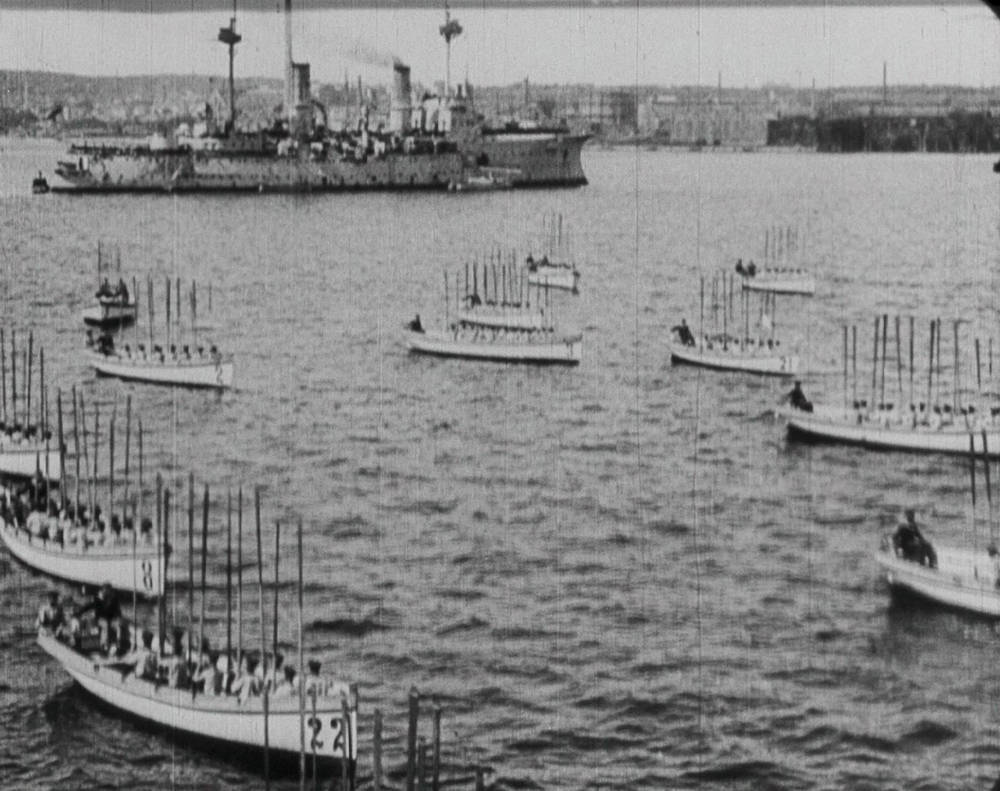

The endless rows of standardized bodies moving in sync in the revues and magazines are distantly reminiscent of the later strictly regimented military parades. The contemporary sociologist Siegfried Kracauer was inspired by this omnipresent serial aesthetic to state: “The hands in the factory correspond to the legs of the Tiller Girls.”

Objectivity and functionalism became the key words of this era. The “Fordism” of the Detroit car manufacturer imported from America provided the blueprint for the manufacture of large volumes on the conveyor belt, production was streamlined in many places, and as a consequence the economy experienced an upswing for a time. The avant-garde and creative minds also showed themselves to be receptive to the new trends. This can be seen, for example, on the signet of the Bauhaus University founded in Weimar in 1919. From 1925 the school used the geometric profile as an engineered portrait of its program. From then on series production and designs adapted for rationality were to define its teaching.

The new man in fascism

The masses signified potential and danger at the same time: rising homelessness, pressure from inflation, streamlined series production and the virulent cult of the body. The “new man” was a construct of a mass society oriented towards rationalization and economization. These developments already harbored initial fascist elements.

February 1933, Berlin. The Reichstag is dissolved and the Nazis come to power. Hitler was to be the dictatorial Reichskanzler for the next 12 years. After 1933 politics began to look to the organization of life, with racial motives being a factor. The cult of the athletic body and the “national mandate” meant the population became a living resource for industry and the military. With the help of the new man, the regime was to gain a face after taking power. Sculptors like Arno Breker and Josef Thorak became popular with their works depicting active, muscular and “Aryan” people.

Monumental and militaristic

These bronze, metal or stone figures came to embody valor, were heroized and served fascist objectives. The physical stance is tense; the male figures always stand erect, and in their nakedness are reminiscent of the physical ideals of the ancient world. The expressively shown mass uprisings in Lang’s Metropolis or the dance-like, ecstatic movements of the sport and gymnastics film “Ways to Strength and Beauty”, which premiered in 1926, gave way to these militaristic and monumental presentations of the unknown “hero”.

NEW DIGITORIAL

The free digitorial provides you with background information about the key exhibition aspects

For desktop, tablet and mobile