Without rain there’s no water, without water there’s no rice farming, without farming there’s no food. Shen Xin’s film “Warm Spell” takes a sensitive look at the economic, ecological and cultural changes in Thailand.

In promotional material of both the printed and digital kind, tour agencies are quick to point out how splendid a holiday in Thailand can be in its “high season”, with talk of warm sunshine and very little rain – and all that in the traditional winter months! Yet increasingly drought is threatening the way of life for the people who live there: In 2016, which saw the greatest period of drought in Thailand for more than 20 years, the government declared more than 4,000 villages to be disaster areas due to water shortages.

For the coming “high season”, extreme drought is being forecast again. In Shen Xin’s video work “Warm Spell” (2018), at the very beginning an inhabitant of the southern Thai island of Koh Yao Yai describes the dramatic effects: Without rain there’s no water, without water there’s no rice farming, without rice farming there’s no food.

An inhabitant of the island describes the immediately dramatic effects

Shen Xin’s work offers a good half-hour of what initially seems like a documentary, but which frequently offers us insights into everyday life for the islanders. This has changed significantly over the last few years, not only due to the existential climatic conditions, but also because tourism on neighboring islands is spilling over more and more onto this previously unknown island, meaning life there is gripped by ongoing change. Both western and Asian tourists are repeatedly caught on camera. One Dutch man who has settled on the island explains how the island’s relatively low prices are attracting an ever greater number of Chinese tourists, many of them farmers who are now able to afford a holiday for the first time. He casually mentions how one resort employs multiple security guards to keep the Chinese tourists out.

Shen Xin took a holiday there a few years ago with his family and had experienced this discrimination. We repeatedly hear from the Dutch immigrant – but while the local residents talk about their day-to-day work or the time before the devastating tsunami, he talks about the magic of the flora and fauna or describes with great fascination how he discovered the previously unknown island some unspecified time ago.

Shen Xin had experienced this discrimination several years ago, along with the family

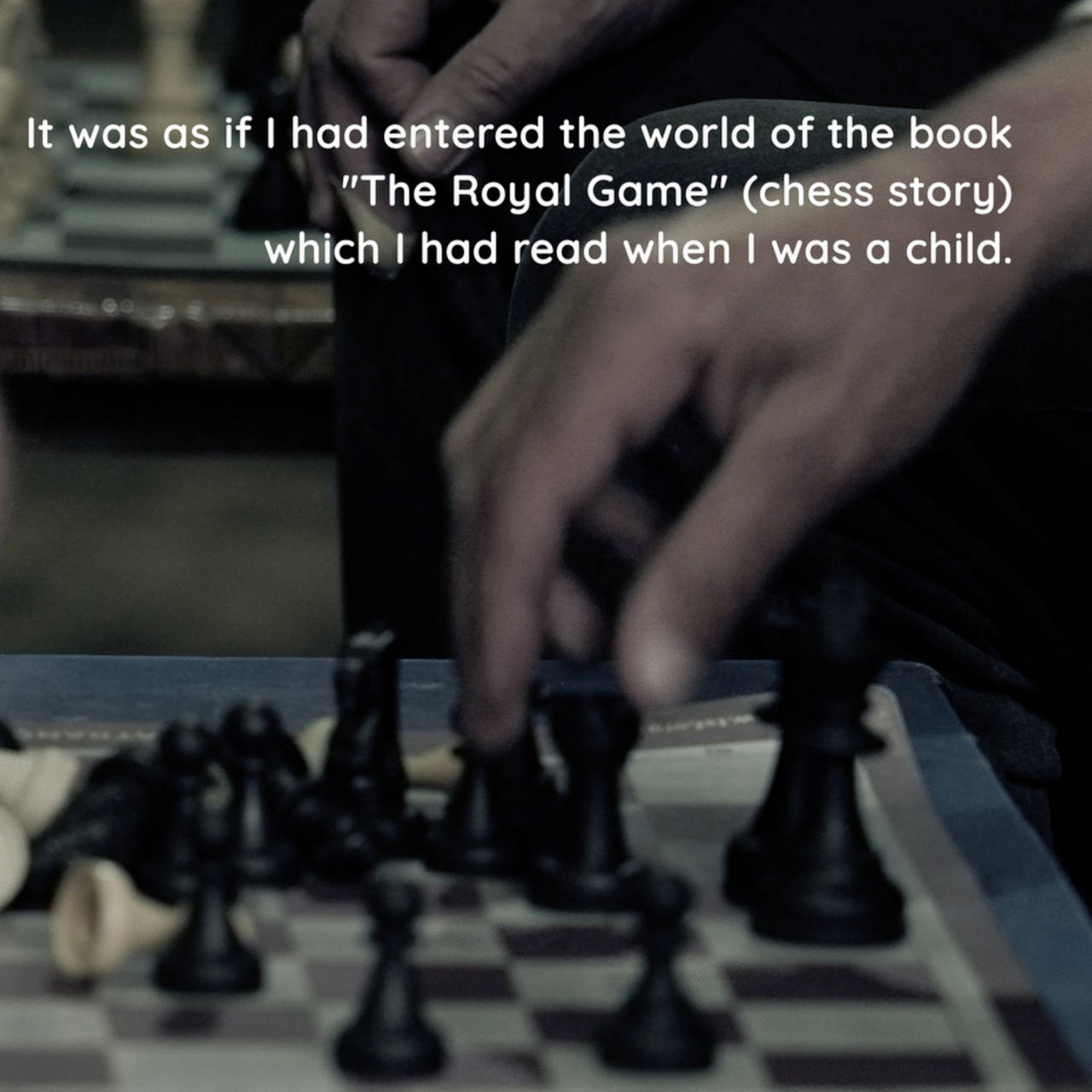

After completing a degree in painting in Singapore, Xin grew ever more keen on the medium of film while studying at the Slade School of Fine Art in London. Works such as “Snow Country” (2013), which deals with the systematic forced prostitution of the so-called “comfort women” by the Japanese military during World War II, or “Provocation of the Nightingale” (2017) – a four-channel installation about a romance between two women, one the manager of a company for DNA analyses and the other a Buddhist teacher – were the result. The themes in “Warm Spell,” unlike earlier works, are more closely interwoven by a sensual experience than by language, as Shen Xin recently stated in an interview with Alvin Li.

SHEN XIN, Provocation of the Nightingale, 2017, Courtesy the artist and the Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art, Image via artasiapacific.com

Early on, “Warm Spell” breaks into a further, seemingly narrative level in addition to the documentary form: Time and again we hear a disruption of frequency on the soundtrack almost like a supercharged electrical field, while the image repeatedly switches into black and white.

The evidently shapeless noise appears to play an active part in the discussion, communicating with the characters in front of the camera in a language that is incomprehensible to viewers, most particularly with a young woman who only appears as Faye in the credits. In a hotel room, the camera captures the protagonist, who writhes naked on a bed, in explicitly intimate acts. In einem Hotelzimmer fängt die Kamera die Protagonistin, die sich nackt auf einem Bett windet, immer wieder bei explizit intimen Handlungen ein. “You sound like electricity,” she says to the invisible conversation partner, “I love it when you do that, you should do it more often.” The Dutch immigrant, who remains nameless, subsequently mentions a wandering ghost, which several of the islanders have told him about.

You sound like electricity. I love it when you do that, you should do it more often.

The beach, which now has several beach resorts, is a magical place, he says, where not everyone can stay for long – and for the locals, one explanation of the ghostly apparitions, simply a cemetery. Thus, bit by bit, “Warm Spell” becomes something of a ghost story, which is gradually distanced from the spoken word and is driven instead by non-verbal emotional states. Similarly to the way the voices of the protagonists sometimes overlap on the sound level, culminating in a not preclusive simultaneity, “Warm Spell” also remains a film essay in the best sense: The ghostly presence of the invisible beings does not supplant the spoken word, which tackles quite specific themes such as ecology, economy and social circumstances.

As an additional film, Shen Xin has chosen “Touch Me Not” (2018) by Romanian director Adina Pintilie. The film was awarded the Golden Bear at the Berlin International Film Festival (Berlinale) in 2018, and has been the subject of heated discussion among critics everywhere. The semi-documentary film is perhaps best described as a kind of cinematographic experimental arrangement about intimacy: Three protagonists, Laura Benson, Tómas Lemarquis and Christian Bayerlein, debate their personal longings and fears in various situations, in each case in relation to their own physicality.

Adina Pintilie, Touch me not (Still), 2018, Image via www.viennale.at

Hence, in various carefully planned situations, Laura attempts to get to grips with her phobia of touch from which she quite evidently suffers. Meanwhile Tómas, who has suffered from alopecia universalis – complete loss of all body hair – since the age of 13, participates in a kind of touch therapy in a hospital where he meets Christian, whose body is also severely affected by spinal muscular atrophy.

The explicit scenes upset some of the Berlinale critics

With its open discussion about intimacy and some, albeit rare, extremely explicit scenes, “Touch Me Not” upset some of the Berlinale critics so much that they left the cinema. Others were captivated, and others still simply found it boring and therefore considered both the Golden Bear and all the hype to be unjustified. Be it a masterpiece of emotion or a concoction of pretention, powerfully impacting scenes like that where muscle-atrophy-sufferer Christian Bayerlein reflects disarmingly on his emotional and his physical perception are rare and hard to dismiss. Be that as it may, here a physically disabled human being is brought out of the state of non-existence and made visible, which perhaps, in an ideal scenario, facilitates discussion with him rather than about him.