Are artists particularly creative when it comes to cooking? A look into the kitchens of the art world, starting with Francis Bacon’s cookbook collection and a bathtub with a view.

Alice Waters, chef and co-founder of the famous Californian slow food restaurant Chez Panisse, describes the relationship between cooking and art as follows: “The most literal visceral connection we make is with food… The acts of art-making and cooking align in many ways; both reactive and creative, they mimic and accommodate one another.”

So, is there a connection between what happens in artists’ studios and what goes on in their kitchens? Amid all the pots and pans, can we find points of references to their work and their personalities? Are artists particularly creative when it comes to the everyday act of cooking? Through photos and inventories of their kitchens, as well as anecdotes relating to their eating habits, we will try to gain an insight into the culinary worlds of some well-known artists. Let’s start with Francis Bacon, his extraordinarily creative use of cookbooks and his bathtub with a view of the fridge.

The most literal visceral connection we make is with food… The acts of art-making and cooking align in many ways […]

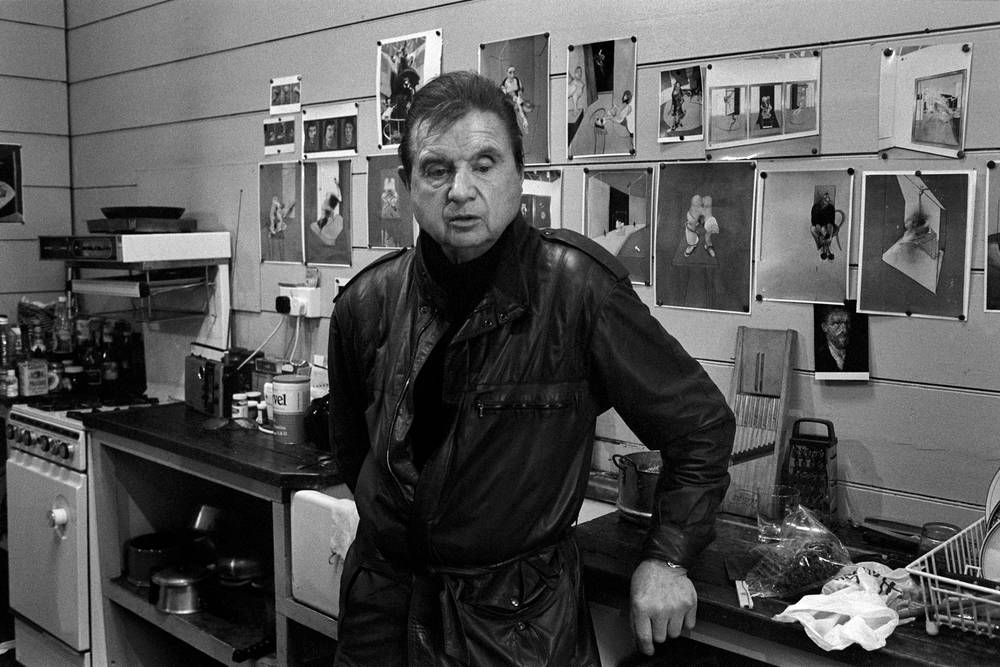

The first floor of a former coach house in London’s South Kensington, which had been converted into a small, two-bedroom apartment, was home to Dublin-born artist Francis Bacon for more than thirty years. The kitchen and bathroom were condensed into one space, while one room served as a sleeping and living space and the other was Bacon’s studio. Looking at the images of his spartan, functional kitchen – a simple gas oven tucked between two battered worktops, a bathtub and wash basin of the most inconspicuous kind, illuminated by one single, naked lightbulb – it seems hard to imagine that at the end of the 1920s the artist made his living as a furniture and interior designer in Paris.

His first studio was furnished in a modern style and served as a presentation space for his designs: Corbusier-like furniture made of steel and glass and rugs with geometric patterns that he hung on the wall. At that time painting was merely a side-occupation for Bacon at that time, but he soon decided to dedicate himself to the medium entirely. After a short phase of abstraction in the predominant style of the post-war period, he developed his own figurative pictorial language, which enabled his breakthrough as an artist.

At first glance, Bacon’s kitchen gives no clues to the identity of its owner. Most of the objects might be found in any working-class home in England of that time, and it’s only on closer inspection that the illustrations tacked to the wall above the worktops become noticeable, showing some of Bacon’s grotesque, almost surrealist-seeming portraits.

Francis Bacon’s Studio (Detail), Image via www.hughlane.ie

Francis Bacon’s Studio (Detail), Image via www.hughlane.ie

On the table between the bathtub and the fridge sits a pile of Bacon’s cookbooks, one of them is “Mrs. Beeton’s Book of Household Management”, an extensive manual on the right way to manage a Victorian household. Bacon owned more than 40 cookbooks, among them four different versions of “French Country Cooking” by Elisabeth David. Yet his own household could not be further from the reality that Mrs. Beeton describes – the manual includes a chapter on dealing with cooks, butlers and chauffeurs. Bacon wasn’t a particularly ambitious cook, but he studied the illustrations in his books meticulously, fascinated by the color, texture and suggestive power of various types of foods. He collected images like those of different cuts of pork and used them as points of reference. Even as a child, Bacon had felt magically drawn to butcher shops and the pieces of meat displayed there, and the motif of the hanging animal carcass appears time and again in his work.

Although he didn’t usually put his cookbooks to their intended use (one of the copies of “French Country Cooking” served him as an unconventional palette), Bacon was not averse to good cuisine, in fact quite the opposite was true. In the company of his lover and mentor Eric Hall, he is said to have learned to appreciate good food, and the two years he spent in Paris cemented his love of French cuisine. Many of the nights Bacon spent in revelry began with oysters and champagne at the Ritz and ended in obscure cellar bars – symbolic, in a way, of the often contradictory aspects of his own life. Hence, his kitchen, too, tells only part of his story: The artist continued to live there in humble surroundings, even when his paintings were already selling for millions.

What do the kitchens of the art world look like?

This way to the culinary worlds of Louise Bourgeois, Frida Kahlo and Georgia O’Keeffe