A young woman studies at the Bauhaus in Weimar and Dessau and struggles not only for a redefinition of art, but also for self-determination as a woman: In her novel “Blaupause” Theresia Enzensberger brings the 1920s to life.

What humiliation! When Luise Schilling receives this letter from her father, a rich industrial tycoon in Berlin, she is disgusted – but she complies anyway. After all, you don’t bite the hand that feeds you. And it was the financial support of her parents that has made it possible for Luise to study at the Bauhaus University in Weimar and later Dessau in the first place.

Dear Luise, Your mother and I have come to the conclusion that it is no longer worth your while staying at the Bauhaus in Weimar. We have secured a place for you at the Pestalozzi-Fröbel-Haus in Schöneberg, and you will start there in June.

Her application to the institution in 1920 was initially not well-received by her family, but when they learned that the Bauhaus also had a weaving workshop in which their daughter might learn something of use to a woman, they eventually acquiesced. Yet Luise, it soon becomes clear, has no intention of sitting at a weaving loom.

Revolutionizing building construction

She wants to become an architect and to revolutionize building construction, to break away from the wild mix of historicizing styles that have prevailed thus far in favor of a clear, structured way of building. First, however, she finds herself in the preliminary course taught by Johannes Itten among his circle of Mazdaznan believers – one has to belong somewhere, after all. What’s more, she’s rather enamored of the handsome Jakob.

Walter Gropius, Bauhaus Dessau, View from Southwest (built 1926), Photo: Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin, Image via DGDB

To put artistic revolution aside for a moment: Luise is primarily in pursuit of herself and her sexuality, and her desire to portray herself as worldly and tolerant, just as any carefully emancipated woman should be. Yet it mustn’t be too excessive; too much liberality such as that in the nightclubs of Berlin unsettles her:

You see heavily made-up faces, glittering costume jewelry, dangerously short skirts, women in tailcoats and smoking jackets, men in evening dresses and half-naked youths who could even be girls. I find it all most peculiar, the lewd atmosphere vexes me so that I really want to turn straight round and go home.

Luise is trapped between the demands she places on herself and the role models that endure among the teachers and fellow students at the Bauhaus: As if he had arranged it with her father, after the first year Johannes Itten sends her to the weaving mill, and although Walter Gropius praises her architectural ideas, he warns her that building an entire settlement would likely be too much for her to handle. Later he brings out her designs under his own name.

Weawing romm at the Bauhaus Weimar, about 1923. Bauhaus-University Weimar. Image via 100 Jahre Bauhaus

The political circumstances of the inter-war years with the gradual rise of the Nazis confuse Luise and raise doubts about her life in the Bauhaus bubble. How can her fellow students fast while inflation has meant that so many people barely have anything to eat? How come there is so little talk of politics at the Bauhaus when, at the time, the signs are more than threatening?

Life in the Bauhaus bubble

Luise faces a daily struggle for recognition of her creative abilities, on the one hand, and her emancipation as a young woman, on the other, and this has her teetering like a poorly built structure at the traditional lantern festival. Yet if protest is not an option, it also doesn’t help that she – just as one did in the 1920s – has her hair cut into a bob and attempts to adopt the attitudes of the “new woman”.

Female self-determination and sexual escapades, clichéd role-models, growing antisemitism in Germany, and amid it all the desire for “new human beings” at the Bauhaus: For her novel, Theresia Enzensberger has chosen a decade which, in hindsight, could not be more dense or complex. Capturing all this in a convincing, flowing novel is an ambitious undertaking, one where the author doesn’t always succeed.

Like a glass ceiling

Too many details – often without any relevance to the action and mentioned simply to add to the period atmosphere – frequently render the text overloaded and sluggish, and this is exacerbated by the first-person perspective of the main character used throughout in real time, which doesn’t allow Luise any form of reflection and highlights the dreadful naivety of the young woman who constantly revolves around herself.

Bauhaus Celebration at Ilmschlösschen near Weimar on November 29, 1924, Foto: Louis Held, Klassik Stiftung Weimar / © Klassik Stiftung Weimar, Image via 100 Jahre Bauhaus

And yet “Blaupause” – the debut novel from this young journalist and publisher – describes with powerful and authentic images the everyday life of students at an extraordinary institution and surprises in that at this very place, considered to be so progressive, the gender stereotypes of the time block the route upwards like a glass ceiling. The journey of a young woman in the thrilling turmoil of the Weimar Republic may sometimes appear somewhat contrived, but it’s well worth a read for anyone wanting to learn more about the atmosphere at the Bauhaus during the “roaring twenties”.

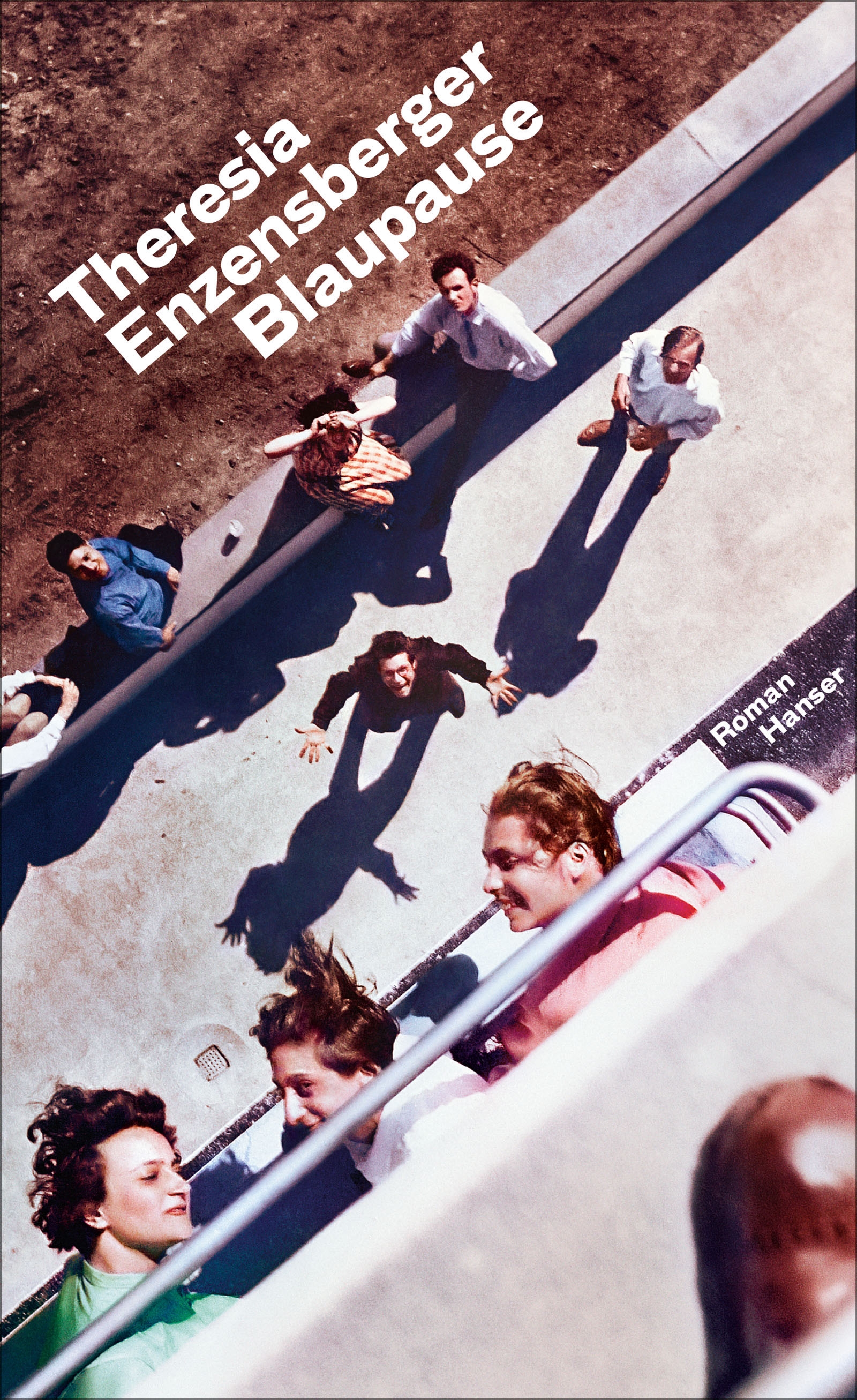

Cover "Blaupause, Image via Carl Hanser Verlag

DIGITORIAL TO THE EXHIBITION

The free digitorial provides you with background information about the key aspects of the exhibition "Splendor and Misery in the Weimar Republic"

For desktop, tablet and mobile

Baby, you can drive my car

For many years now, the art world has had a (love) relationship with cars, be it as a way of representing speed or critical reflection on consumerism....

The film to the exhibition: Selma Selman. Flowers of Life

Only a few years ago, she boldly and confidently entered into the spotlight of the international art world. In this video interview, she talks about...

Selma Selman and the elastic fabric of the Self

SELMA SELMAN's artistic practice cannot be described as site- or situation-specific; rather, it seems to deal with the self and its constant...

Now at the SCHIRN: CASABLANCA ART SCHOOL. A POSTCOLONIAL AVANT-GARDE 1962–1987

The Moroccan “New Wave”: The SCHIRN presents the influential art scene around the CASABLANCA ART SCHOOL in a first major exhibition in Germany.

FIVE GOOD REASONS TO VIEW SELMA SELMAN IN THE SCHIRN

Poetic, confrontational, surprising: from June 20 to September 15, the SCHIRN presents two new works by the artist SELMA SELMAN in a large solo...

A Sicilian myth in a contemporary guise

What if women can resolve and heal dichotomies? In the coming DOUBLE FEATURE, Elisa Giardina Papa takes the Sicilian myth of the “donne di fora” and...

REVISITING DOUBLE FEATURE: FOCUS ON QUEER ART

Our DOUBLE FEATURE series presents a variety of artists who deal with queerness in their work. We have selected some of the best video interviews for...

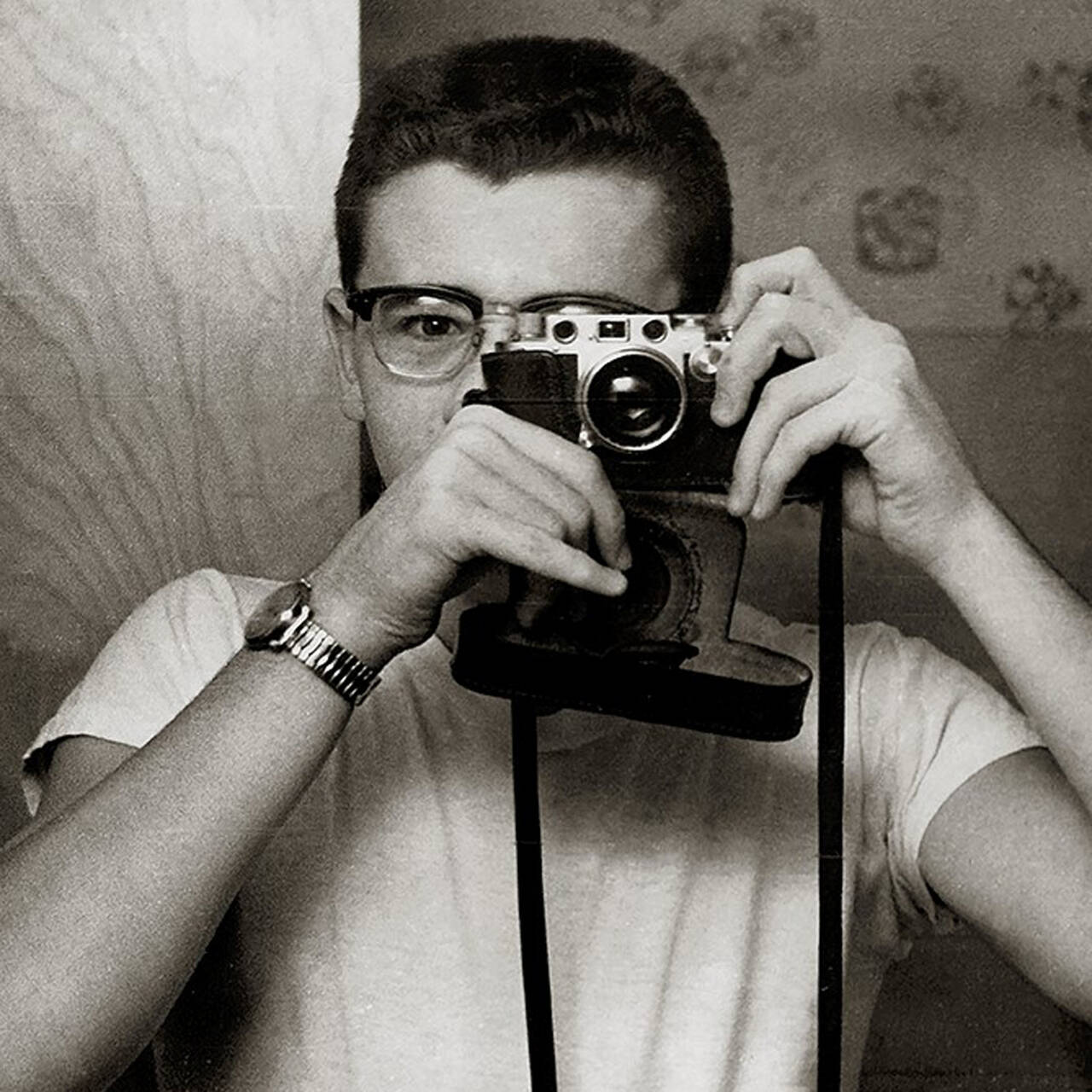

ABOUT TIME. With Abe Frajndlich

Abe Frajndlich can look back proudly on a career of over 50 years as a photographer. In conversation with us he speaks, among other things, about his...

A mix of meditation and leisure

What potential does leisure offer? What happens if nothing happens? In the form of “Untitled (Nothing Happens)” (2023), in the latest DOUBLE FEATURE...

Doing nothing is (not) at the core of the work

Jovana Reisinger reflects on idleness in Cosima von Bonin’s work – is it a sign of luxury, slovenliness, or ultimately a much more meaningful and...

Toxic cuteness

Cuteness overload! Bambi is a recurring reference in COSIMA VON BONIN'S visual world. But such a saccharine appearance can be deceptive. What are the...

From studio to dining table: The (food) culture

Are artists particularly creative when it comes to cooking? We take a look around the kitchens of the art world, this time at the interface between...

Daffy Duck. Here’s to imperfection!

Daffy Duck is an integral part of COSIMA VON BONIN’s artistic oeuvre, but what’s the story behind this polarizing cartoon character?

Where are the hip hop Hotspots in Germany?

Hip hop culture has long since become an integral part of life in German cities. From Frankfurt and Heidelberg through to Bietigheim-Bissingen near...

Improvisation and failure as creative motivation

John Cage’s “Untitled Event” (1952) is felt to mark the birth of performance art, but there is only anecdotal evidence as to what it actually...