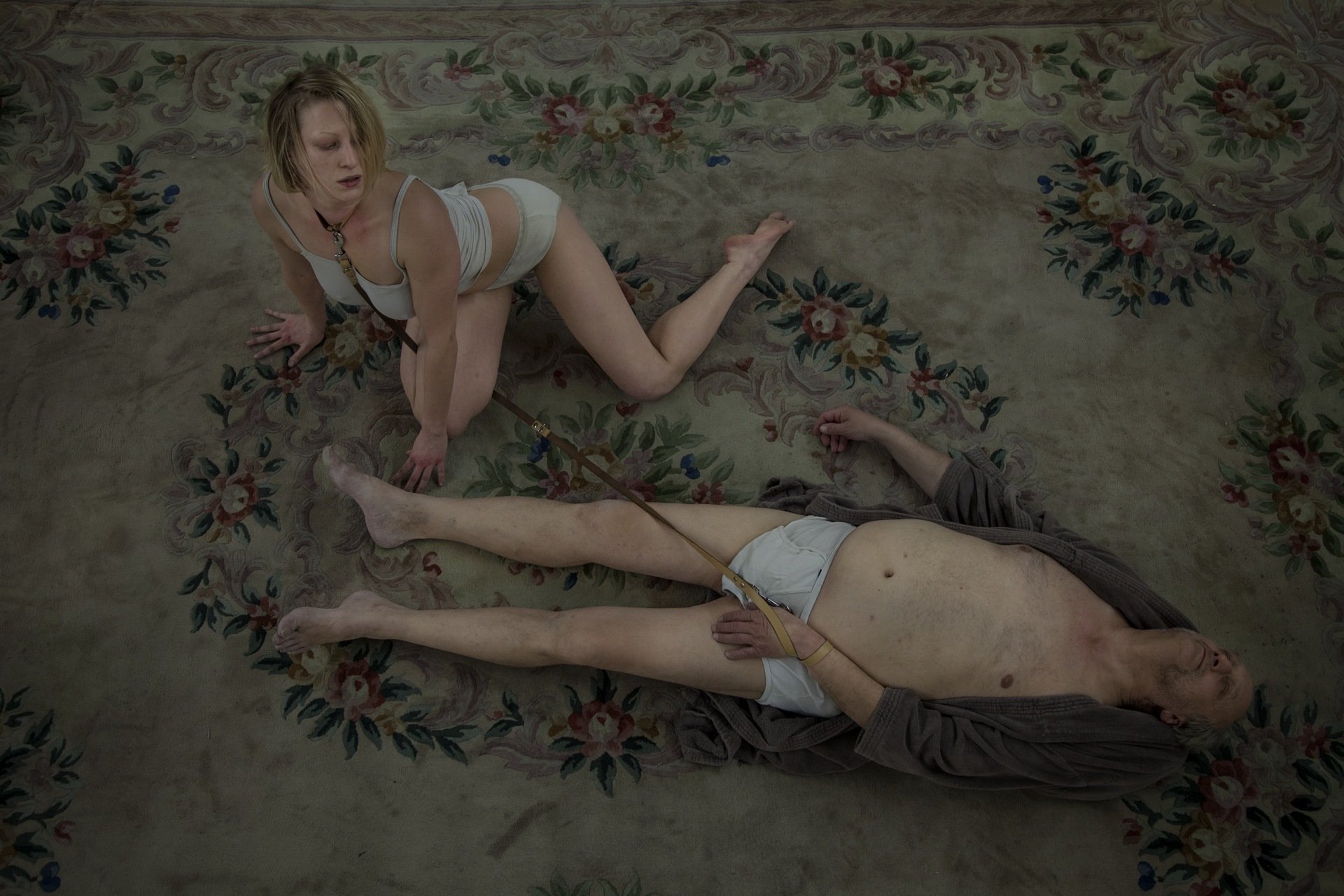

Its productions turn the theatergoer into an actor: An interview with performance collective SIGNA about immersion, fiction and its play “Das halbe Leid” (A sorrow shared) in Schauspiel Hamburg.

What does the concept of “immersion” mean for you and your work?

Signa Köstler: It is not that important for us. I would argue that currently everything conceivable is being crammed into the term “immersive theater” including a lot of stuff that has nothing to do with our work. Given all these events on the topic, the idea is certainly really being hyped at present. What all the productions have in common is that they don’t take place on a stage, but that does not necessarily mean you can draw any comparisons.

The difference between “classic theater” and your projects is that the viewers not only get involved with their mind, but immerse themselves with their entire bodies. As theatergoers, we walk through the scenery and interact with the actors; there is no “fourth wall”. Was it planned that way from the start?

Signa: Yes! I suppose the main reason for that was that I had no theater background at all, and neither does Arthur [Köstler, media performance artist and member of SIGNA, editor’s note]. I didn’t conceive of the whole thing as theater, I didn’t start out with the intention: “Now I will break through the fourth wall!” There was no fourth wall for me; I didn’t connect it with theater at all. Ultimately, it developed into a theater context, because we got our funding there and collaborated with actors and theaters. My actual starting point was an installation. I studied Art History and gradually worked my way towards 3D installations, but after my first project, which did not get screened, I realized that actually I always need to be present. Later, I had my projects “inhabited” by other figures.

So it was a kind of process that brought you to where SIGNA now stand?

Signa: Yes, but it was a very fast process! I only produced a single “uninhabited” installation. I could think of no dialog, and without dialog it made no sense. Back then it was important to ask what a “fictional character” is – after all a written figure with its own biography is nonetheless a version of me. I spent a lot of time thinking about alter egos, identity and the border between reality and fiction.

Does the border between reality and fiction play a less important role now?

Arthur Köstler: We have more or less abandoned it.

Signa: Well, it’s still a topic for me. But at some point I was convinced you can never know exactly when something is reality and when fiction, and that the borders are fluid. After a certain time, it was no longer as important, we were more interested in other aspects of the productions.

Arthur: We tried to divert focus away from it, because suddenly so much weight was given to this divide, as if it was the only concern around.

Signa: You don’t need perpetually to ponder what is fiction and what is reality or “what am I, and what is invented”.

An important part of immersion is the transition from the real world to the “parallel world”. How is that handled in SIGNA productions, especially when they last for several days?

Signa: The latest production “Das halbe Leid” lasts twelve hours and has a capacity for 50 participants, who all come in simultaneously. Everyone has a bed, and stays the entire twelve hours. Of course, you can stop it earlier, but that is not really the point. Other performances last one or even two weeks non-stop, and people could come and go as they wished.

Arthur: As regards the transition in the piece “Das halbe Leid”, people are told beforehand that they are attending a course in a club. So they come in, and are in the club – nobody explains the rules or anything like that. As soon as the door opens, there is only fiction in the ensuing 12 hours.

How do people respond to this kind of production?

Arthur: In those pieces that last for several days where people come and go it is often the case that the visitors think in characters and their story, which is continued, while they are not there. And then they visit the characters they have got to know over a certain time, again – and are really happy after seeing them.

Signa: Naturally, the transition, the entering, is different in longer pieces, because there is an ongoing development. If you don’t get involved until day three, then you have already missed quite a lot. But strictly speaking it is no different from being a member in a club – and clubs have always existed already before.

How many participants are classic theatergoers more accustomed to staying seated, while the play is performed on the stage in front of them?

Signa: That differs. Premieres are frequently attended by people visiting us for the first time. But a lot of people come more often and are familiar with how things proceed, and what is expected of them.

For participants it is perhaps also an opportunity to assume a role they would not otherwise have?

Signa: Yes, and no – I suppose it is, but I believe that you have a much better experience when you don’t take on any role, but experience it as yourself. As if you really were in this fictional situation. Of course, you know that you are in something staged, but it works better, if you let events affect your actual self. Thanks to our productions it is possible for someone to suddenly behave differently precisely because of this shifted reality. You can express things you would not normally say, can experiment with different responses – because there is not the same binding nature as in real life.

What do you find so fascinating about thinking yourself completely into a different biography and also immersing yourself in the banal things of everyday life?

Signa: Well, I have thought about it. I have been doing it now for 17 years, but it is (still) not easy to explain.

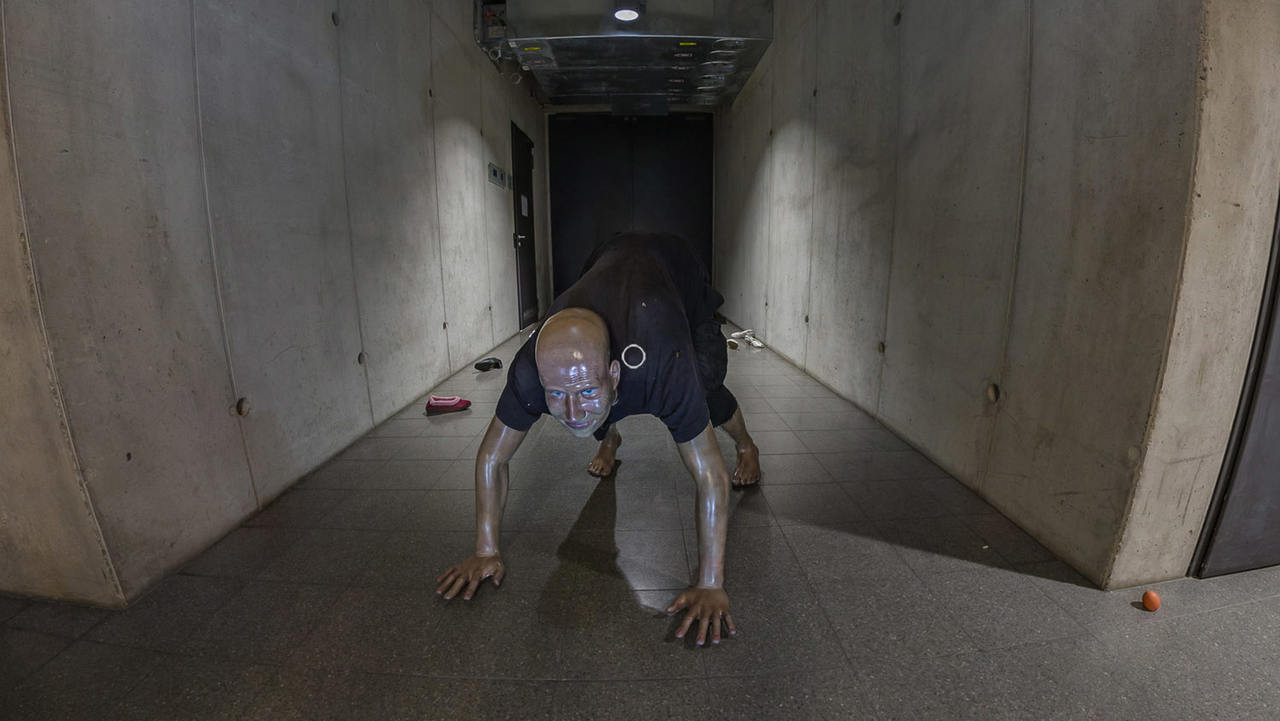

Arthur: It is not so much a matter of thinking yourself into a character. The fascinating thing is more creating a figure, which moves in society, and then seeing what this figure encounters. The interesting thing is not what constitutes this figure, but what it triggers. As actors we don’t lose ourselves in roles, we haven’t suddenly forgotten everything else – we are very well aware of every aspect of the show: Where are the other actors, how must I react now, does the whole thing come over well. Ideally, everything is harmonious. The picture is just as important as smell, sound and action, you have to constantly produce everything together. We sit on the figure the way you sit on a bike.

Spontaneity is key to your productions. Do you nonetheless have a “timetable” for them?

Arthur: We have a logistical timetable. We make sure all the rooms are occupied, and not everyone is in one place at the same time. There are events that take place within “Das halbe Leid”, and there is a timetable.

Signa: You can plan a lot of things, though we try to leave open those things that you can’t plan in real life either. But the concepts do vary. In some productions we only work on a skeleton story in advance and then improvise. In other pieces participants have exactly 18 minutes in a room with the actors before they continue to the next one. You can control a lot if you want, but you don’t always want to.

How Virtual Reality conquers the art world

Ever danced with a wolf? Artist duo Djurberg & Berg make it possible with their first virtual reality work. They are part of a young generation of...

The enemy of my enemy

From August 23 onwards, a unique project by artist Neïl Beloufa will transform the SCHIRN into a stage. Palais de Tokyo is currently hosting Beloufa's...

In the vicious circle of sadness

As part of the “Immersion” series, British artist Ed Atkins is presenting an exhibition at Martin-Gropius-Bau that addresses our ubiquitous escapism...

From window to pool

The distance between viewers and film is becoming ever smaller. Even 120 years ago, cinemagoers were jumping out of their seats as a locomotive...

A walk-in diorama

These days, computer games are discussed in arts supplements. What is their appeal and how do they develop such a strong draw for people? Let’s play!

Hats off, it’s Wagner

The opera “Mondparsifal Beta 9-23” by Jonathan Meese at Berliner Festspiele draws visitors into a cosmos where logic plays only a subordinate role.

Complete dissolution

Is complete immersion in a virtual world a utopia or a dystopia? These and other questions are answered by Prof. Rupert-Kruse, immersion researcher,...

Noise interference from a distant world

An experience for all the senses: An exhibition at Kunstverein Frankfurt invites viewers to immerse themselves in virtual and constructed worlds

Who lives here?

Visitors can immerse themselves in a long bygone era at the Dennis Severs House in London. A truly great experience.

A journey back in time to a divided Berlin

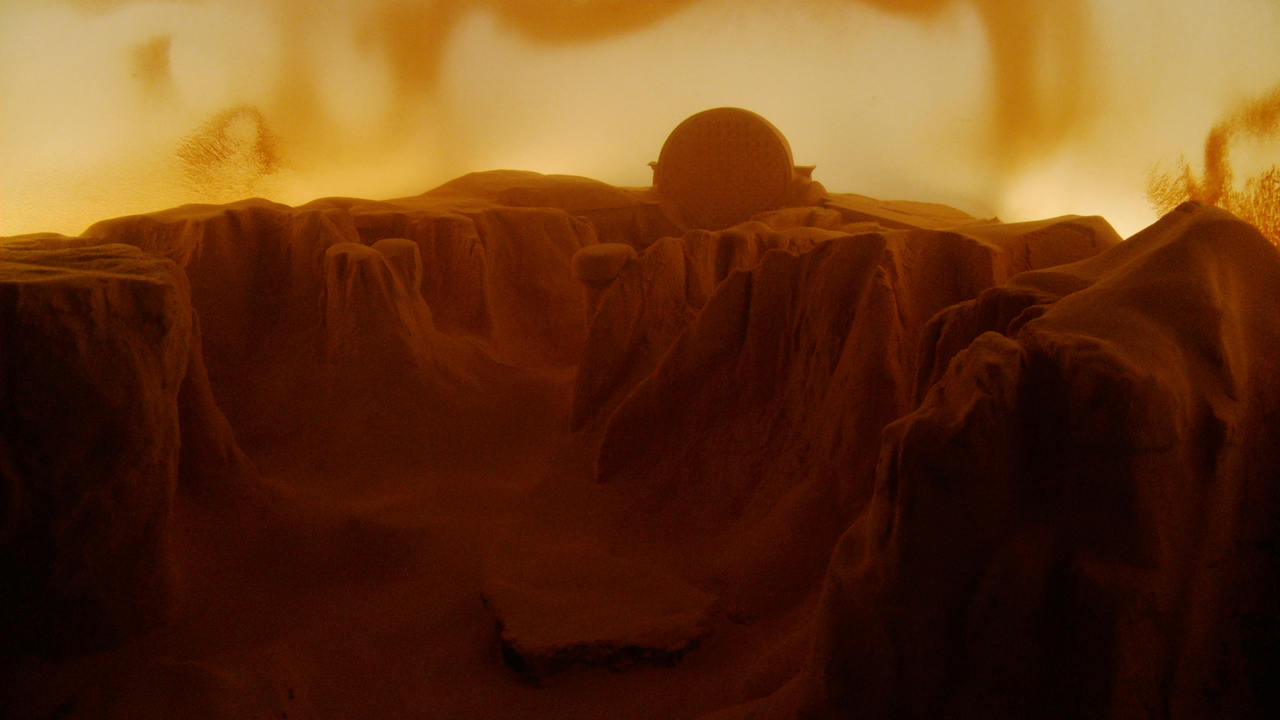

It might not look very exciting from the outside: A large black rotunda that has landed on the onetime “Death Strip” of the Berlin Wall like a...

Diorama. Inventing Illusion

Reality or illusion: The SCHIRN presents a major exhibition dedicated to the idea of staged vision.

Zombies like us

The Internet is full of the undead. The artist duo New Scenario makes them visible — in works that function online, and even offline sometimes.

The dream of watching in 360°

Humans have always had a burning desire to watch, to observe. Now, virtual reality is opening up entirely new possibilities for the creation of...

Exhibited realities

In the exhibition “Diorama. Inventing Illusion” artists question staged visions and reconstructed realities. In modern everyday culture, this...