When Sigmund Freud’s “Die Traumdeutung” (The Interpretation of Dreams) was published in 1900, Richard Gerstl was just 17 years old. He was one of the first to buy it.

Whereas at the turn of the century artists in Berlin or Paris, influenced by industrialization, turned towards more realistic forms of depiction and everyday motifs, Vienna was still considered rather conservative. And even with the formation of the Vienna Secession and representatives such as Gustav Klimt, artists tended to concern themselves much more with symbolism, myths and allegories rather than social problems.

By contrast, Gerstl was interested in critical reflection and exploration of the self: dissonance rather than pure aesthetics, instincts instead of conformity. He followed theoretical and philosophical debates with great interest and concerned himself with musicology and theatre. He read authors such as August Strindberg, Frank Wedekind and Arthur Schnitzler, who addressed taboo topics like sexuality and death, engaged in social criticism and tended to favor concise colloquial language over elaborate digressions when making their everyday observations. And he read Freud, who with his dream theory not only developed the foundations of psychoanalysis, but also had an enduring influence on 20th-century Western culture and its underlying concept of the human being.

What gives rise to dreams?

It is highly likely that Gerstl bought the first edition of “The Interpretation of Dreams” from Hugo Heller’s bookstore, as the go-getting journalist, publisher and concert director was a close friend and great admirer of Sigmund Freud. In “The Interpretation of Dreams” Freud developed a means of interpreting dreams, which he saw as “a psychological structure, full of significance”: What material gives rise to dreams? How are they triggered? And why do we forget what we dreamt after waking up?

Sigmund Freud, Photo Ferdinand Schmutzer [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Freud argued that explaining dream imagery was crucial not only for understanding psychological disorders such as phobias, obsessions and delusions, but also for developing appropriate forms of therapeutic treatment. To this end he examined 200 dreams of his patients, including his own. This was a “painful but unavoidable necessity,” wrote Freud in the preface to his book. “The Interpretation of Dreams” was expanded several times; a total of eight revised editions were published. The most important insight was that there is an underlying logic even to unconscious thought and that the dream, according to Freud, is “a psychic act full of import,” whose driving force represents “wish-fulfilment,” in other words suppressed or repressed wishes are manifested in dreams.

A complex oeuvre

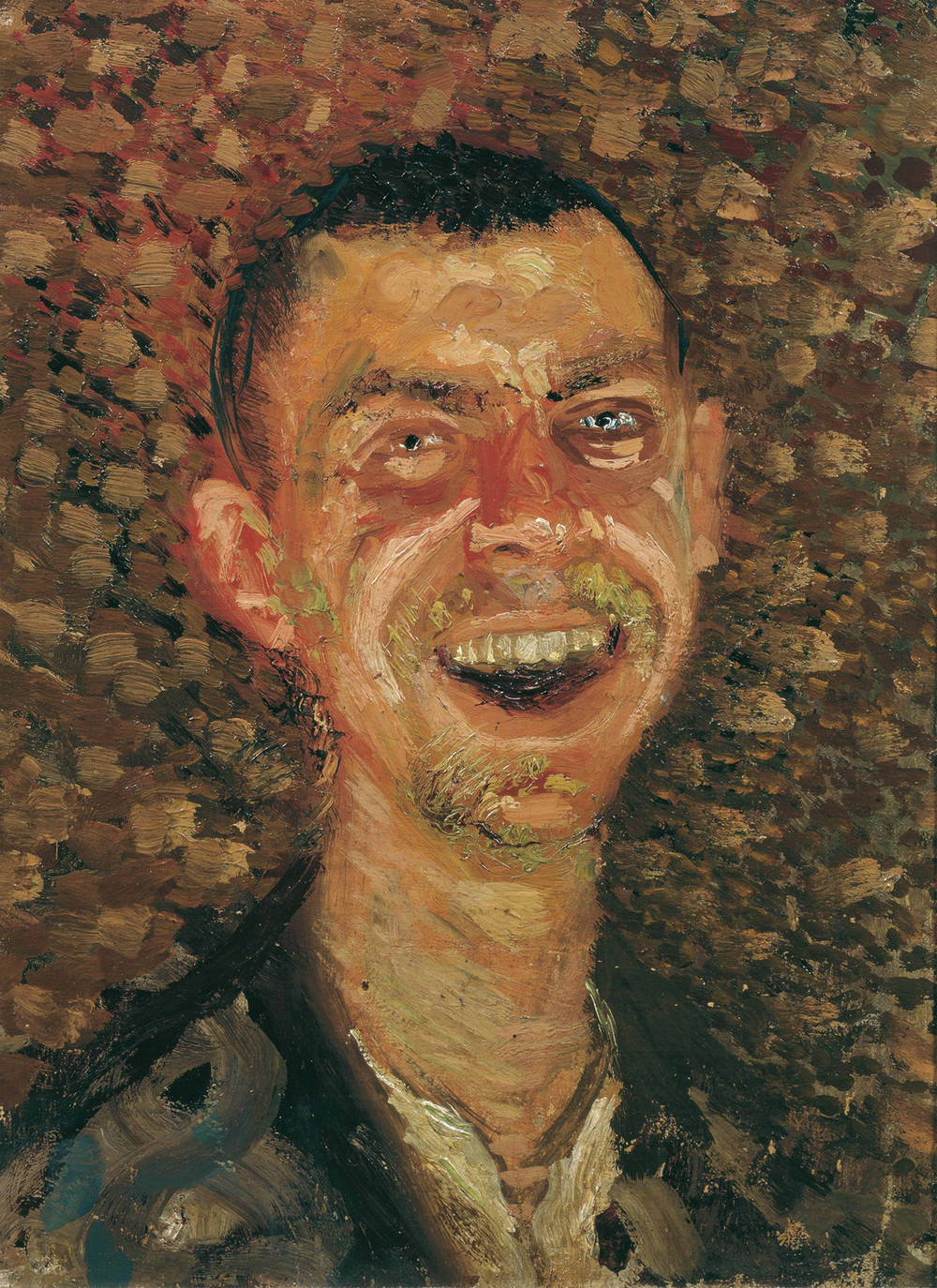

In October 1908 Richard Gerstl set up a new studio vis-à-vis Sigmund Freud’s consulting rooms in Liechtensteinstrasse, Vienna. There he painted one of his final works, “Sitzender Frauenakt” (Seated Female Nude), depicting the nude Mathilde Schönberg, and there just one month later he took his own life. Though he may not have left behind a huge body of work, it is a highly complex one, in which above all the portraits he made of his parents, lovers or friends stand out.

Although it was often the case that his subjects did not like their own portraits, they do reveal an intensive study of the people in question and point to the artist’s sensitive and attentive eye. Similarly, in the many self-portraits depicting him laughing manically, with a faraway expression, or nude, the artist explores his body, his sexuality, his role as an outsider and the sentiments of his own emotional world.

Illuminating people

With “The Interpretation of Dreams,” Freud laid the foundations for discussing the Oedipus complex, fear of castration, or the primal scene fantasy. He explored suppressed feelings, sexual desire, neurosis, trauma and the death wish. In short, he studied people’s emotions and their existence in the modern world. As such, Gerstl’s intense interest in Freud is not surprising. After all, as Ingrid Pfeiffer points out in her essay in the exhibition catalog, in the early 20th-century Vienna was dominated by an uneasy feeling, a collective practice of suppression, which Freud considered to be pathological. By contrast, Gerstl “seems to have worked through the subliminal tensions of his era like a seismograph” and in his urgent desire to illuminate people and things was ahead of many of his contemporaries.

5 questions for Mary Messhausen and proddy produzentin

With the performance "Thonk piece: Hungry for Stains", drag queens Mary Messhausen and proddy produzentin will open the exhibition COSIMA VON BONIN....

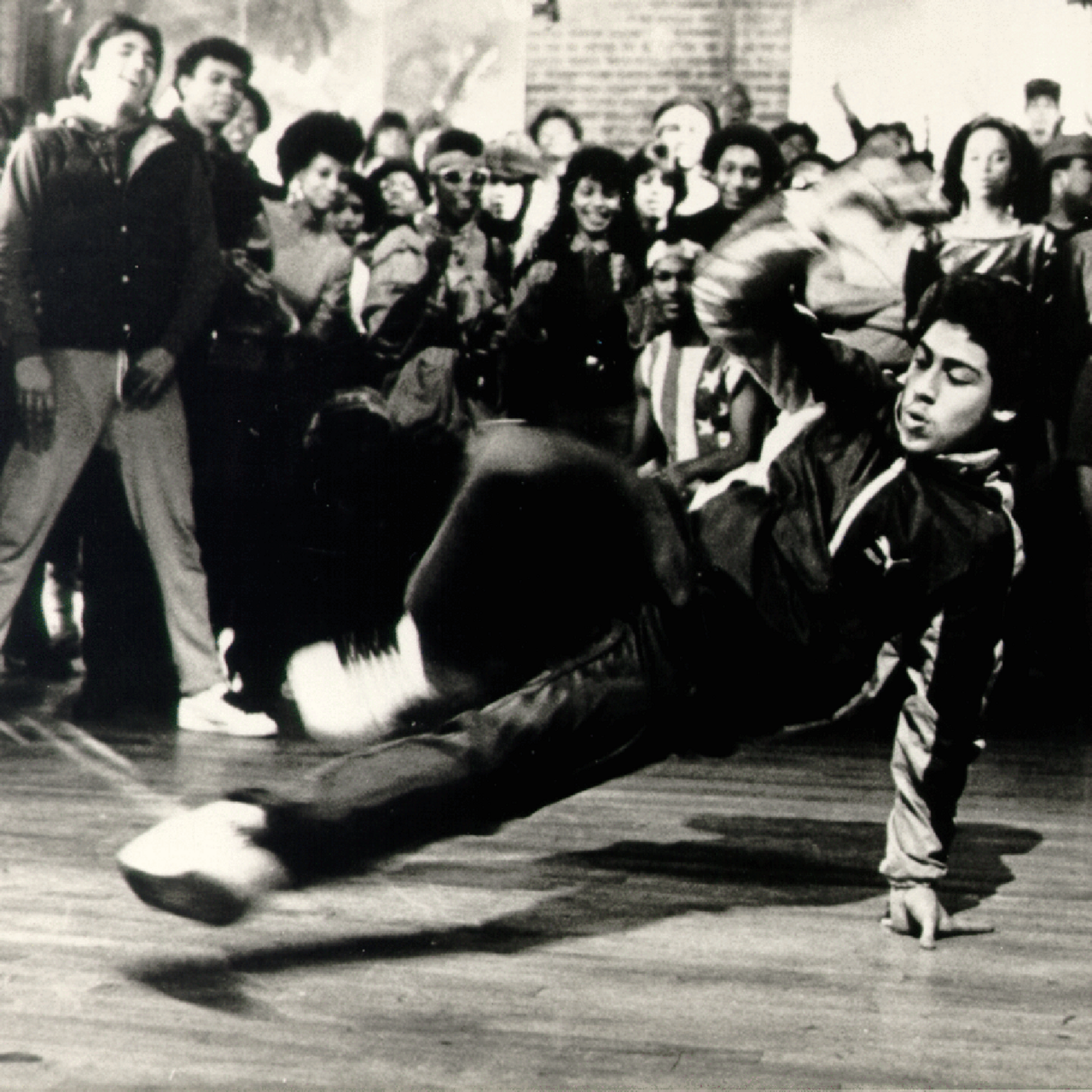

HIP HOP IS BLACK CULTURE – NOT THE OTHER WAY AROUND

Hip hop’s 50th birthday is an occasion for us to listen to some old records and mixed tapes and to look back at the most important hip hop films of...

Now at the SCHIRN:COSIMA VON BONIN

The SCHIRN is showing a unique presentation of new and well-known works by COSIMA VON BONIN until June 9.

You Get the Picture: On Movement and Substitution in the Work of Lena Henke

The artist LENA HENKE already exhibited in the SCHIRN Rotunda in 2017. What are the secrets of her practice and where can you find her art today?

SHALLOW LAKES – plumbing the depths

In the SCHIRN’s rotunda, MELIKE KARA is presenting a series of sculptures that are reminiscent of bodies of water or small lakes. So, what’s this...

When subculture becomes mainstream – a balancing act

Regardless of whether it is hip hop, techno, or the queer scene: It is not unusual for the aesthetics of countercultures and subcultures to morph into...

Now at the SCHIRN: THE CULTURE: HIP HOP AND CONTEMPORARY ART IN THE 21ST CENTURY

Coinciding with the 50th anniversary of the birth of hip hop, the SCHIRN dedicates a major interdisciplinary exhibition to hip hop’s profound...

Julia Feininger – Artist, Caricaturist, and Manager

Art historians can tell us a lot about LYONEL FEININGER, but who was Julia Feininger and what legacy did she bequeath to the world of art?

Lyonel Feininger and the Harvard Art Museums. Part 2

The Harvard Art Museums host the largest Lyonel Feininger collection in the world. The directors Lynette Roth and Laura Muir chat about Feininger’s...

Five good reasons to view Melike Kara in the SCHIRN

From February 15, the SCHIRN presents a new site-specific installation by Melike Kara in its public rotunda. Here are five good reasons why it's worth...