How did painting develop? René Magritte examined the ancient myths surrounding the origin of art and its purpose. We hunt for traces.

Her beloved had to go off to sea, so the young Corinthian woman sketched the silhouette of his profile on the wall. And it was thus, according to the legend by Roman scholar Pliny the Elder, that painting was born. Shadows as the origin of painting.

René Magritte saw himself as a painting philosopher: He worked intensely on painting and the myths of its development. This is evidenced in particular by those themes that arise time and again in his work: curtains, flames, shadows, caves. They point to legends and allegories that question the status of images and their relationship with reality. It is from this first origin myth that Magritte derived three prime elements of his pictorial vocabulary: candle, shadow and silhouette.

Dazzle and sensory confusion

The silhouette of the beloved is not the man himself, it is merely his semblance. Magritte plays with different elements of reality and conflates and interlaces them in a playful way. The most prominent example of this is of course “The Treachery of Images (This is not a pipe)” from 1929. Although the abovementioned themes do not appear here, Magritte distinctly clarifies the difference between perception, similarity and reality.

Caius Plinius Secundus. Lithograph by Dumont, Image via commons.wikimedia.org

Magritte examined Plato’s Allegory of the Cave in great detail. The allegory tells of people who live chained up in a cave and see only the shadows of objects cast on the wall of the cave by a fire located behind them. They know and see nothing of anything outside the cave, hence the captives perceive the shadows as the sole truth. If one of them were to be set free, he would be dazzled by the light and confused by all the sensory stimulation, and would therefore perceive nothing of the outside world as real aside from that which he knows: its shadows.

The shadow is the truth

Magritte tackles the Allegory of the Cave most strikingly in his work “La Condition humaine” (“The Human Condition”). Here the inhabitant of the cave seems to have already been freed, as he looks at the opening to a cave from the inside. The opening reveals a view of a landscape in the distance. In the middle of the opening, however, stands an easel on which there is a picture that appears to show the landscape behind it, or perhaps not. Right next to it burns a fire, another recurring motif. The painting is not a reflection of the world, but rather the imitation of a reality. The shadow – and thus the painting – is its own form of truth.

Magritte also uses the Allegory of the Cave as the basis for his own surrealist manifesto, with which he aimed to reform Surrealism, calling on the movement to “leave the cave”. It was this appeal, however, that soured his relationship with the writer and leading surrealist André Breton. Following on from this Magritte began his subsequent “Période vache”, in which he aimed to imitate the sensory effect that the residents of the cave would experience on leaving the cave and receiving their first sight of reality.

The Treachery of People

By far the most frequent theme found in Magritte’s oeuvre, however, is curtains. These in turn relate to another myth on the origin of painting, “Naturalis historia” by Pliny the Elder. One day the Greek artist Zeuxis painted a picture of grapes that looked so real that sparrows flew by and tried to pick the fruit. His painter colleague and rival Parrhosios saw it and asked Zeuxis to come to his studio to look at a painting. He urged Zeuxis to draw aside the curtain in front of the picture, but when he tried, he found that the curtain itself was a painting. Thus Zeuxis was forced to concede defeat to his rival, since he had succeeded in deceiving not merely an animal, but a human being.

Zeuxis and Parrhasios, Image via akg-images.co.uk

Magritte, in painting a curtain that is as realistic as a work of trompe l’oeil, on the one hand demonstrates his artistic skill. On the other, at the same time he places it in an ironic context, as he shows his illusionist effect, as, for example, in “Le soir qui tombe” (“Evening Falls”). Here we see a window that is, of course, flanked by curtains. The view from the window shows a landscape with sunset.

The truth in little pieces

Yet the glass from the window is partly broken and lies on the floor. In the shards of glass we can see fragments of the same landscape and sunset reflected. In this case the curtains serve only for the subtle reference to the myth. The glass shards look as if they could cut you, but at the same time you get the urge to pick them up and marvel at the sunset reflected on them. Magritte is a master of having the truth shatter into small pieces in order to reveal the many ways in which they could be put back together.

5 questions for Mary Messhausen and proddy produzentin

With the performance "Thonk piece: Hungry for Stains", drag queens Mary Messhausen and proddy produzentin will open the exhibition COSIMA VON BONIN....

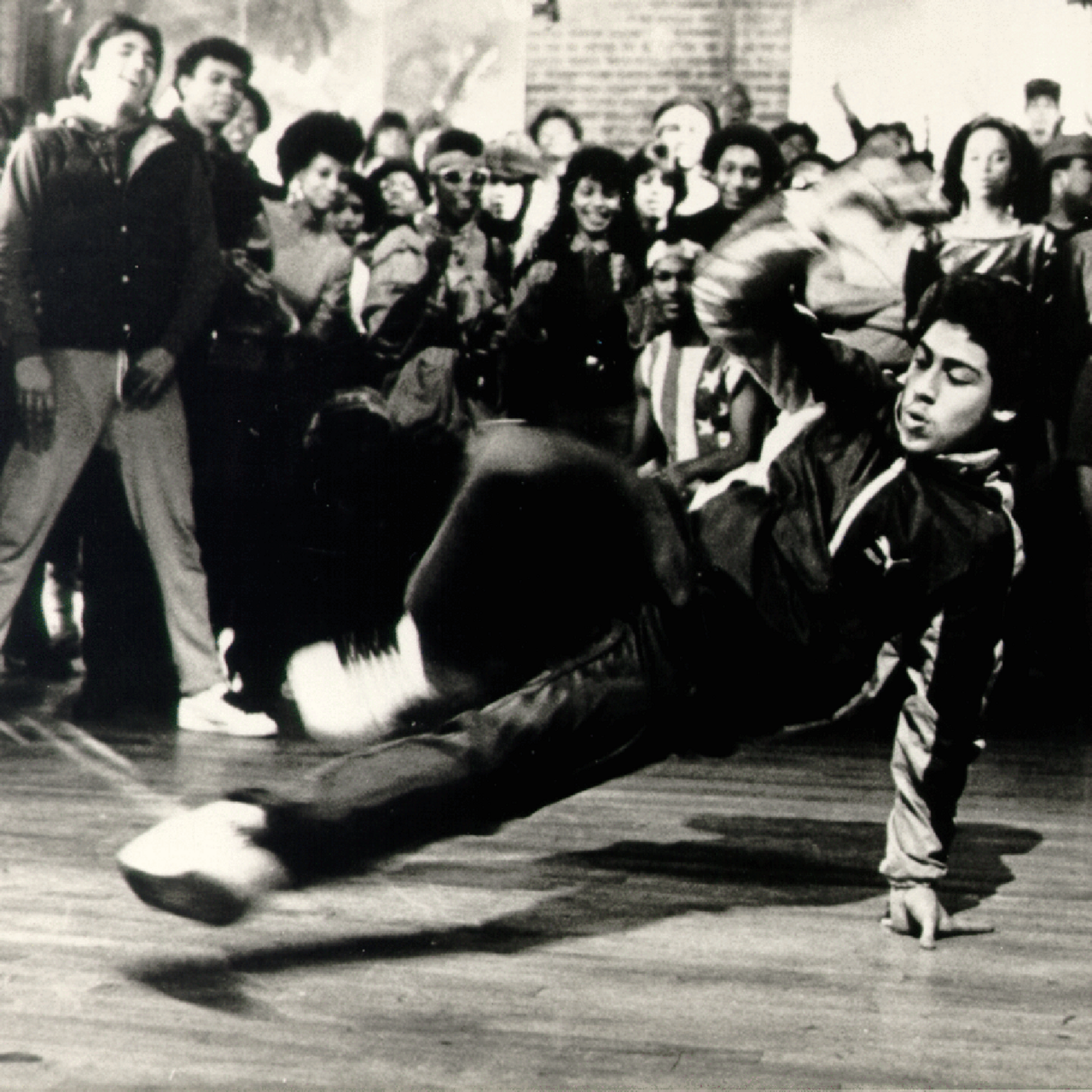

HIP HOP IS BLACK CULTURE – NOT THE OTHER WAY AROUND

Hip hop’s 50th birthday is an occasion for us to listen to some old records and mixed tapes and to look back at the most important hip hop films of...

Now at the SCHIRN:COSIMA VON BONIN

The SCHIRN is showing a unique presentation of new and well-known works by COSIMA VON BONIN until June 9.

SHALLOW LAKES – plumbing the depths

In the SCHIRN’s rotunda, MELIKE KARA is presenting a series of sculptures that are reminiscent of bodies of water or small lakes. So, what’s this...

When subculture becomes mainstream – a balancing act

Regardless of whether it is hip hop, techno, or the queer scene: It is not unusual for the aesthetics of countercultures and subcultures to morph into...

Now at the SCHIRN: THE CULTURE: HIP HOP AND CONTEMPORARY ART IN THE 21ST CENTURY

Coinciding with the 50th anniversary of the birth of hip hop, the SCHIRN dedicates a major interdisciplinary exhibition to hip hop’s profound...

Julia Feininger – Artist, Caricaturist, and Manager

Art historians can tell us a lot about LYONEL FEININGER, but who was Julia Feininger and what legacy did she bequeath to the world of art?

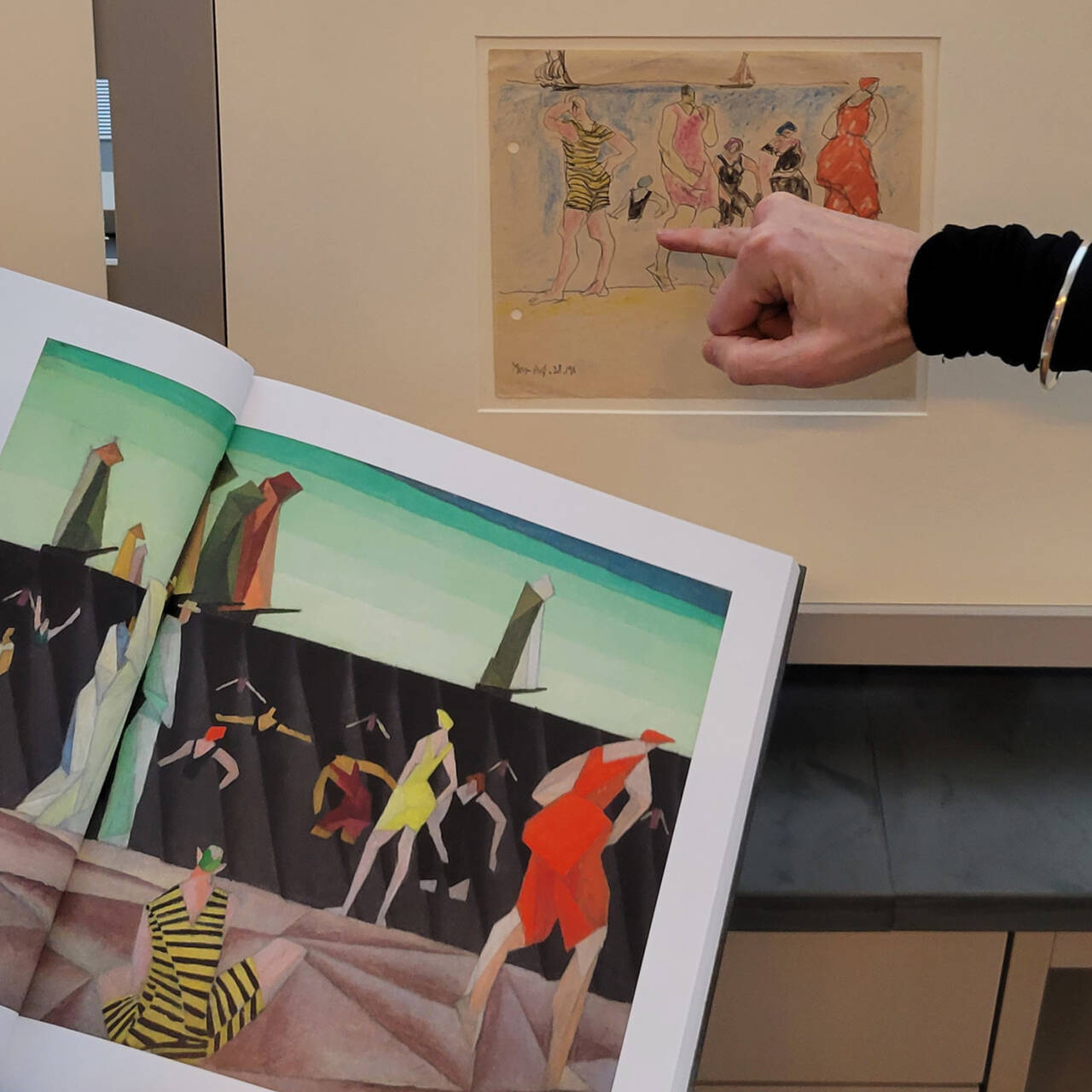

Lyonel Feininger and the Harvard Art Museums. Part 2

The Harvard Art Museums host the largest Lyonel Feininger collection in the world. The directors Lynette Roth and Laura Muir chat about Feininger’s...

Five good reasons to view Melike Kara in the SCHIRN

From February 15, the SCHIRN presents a new site-specific installation by Melike Kara in its public rotunda. Here are five good reasons why it's worth...

Lyonel Feininger and the Harvard Art Museums. Part 1

The Harvard Art Museums host the largest Lyonel Feininger collection in the world. How did that happen and how was the relationship between the artist...