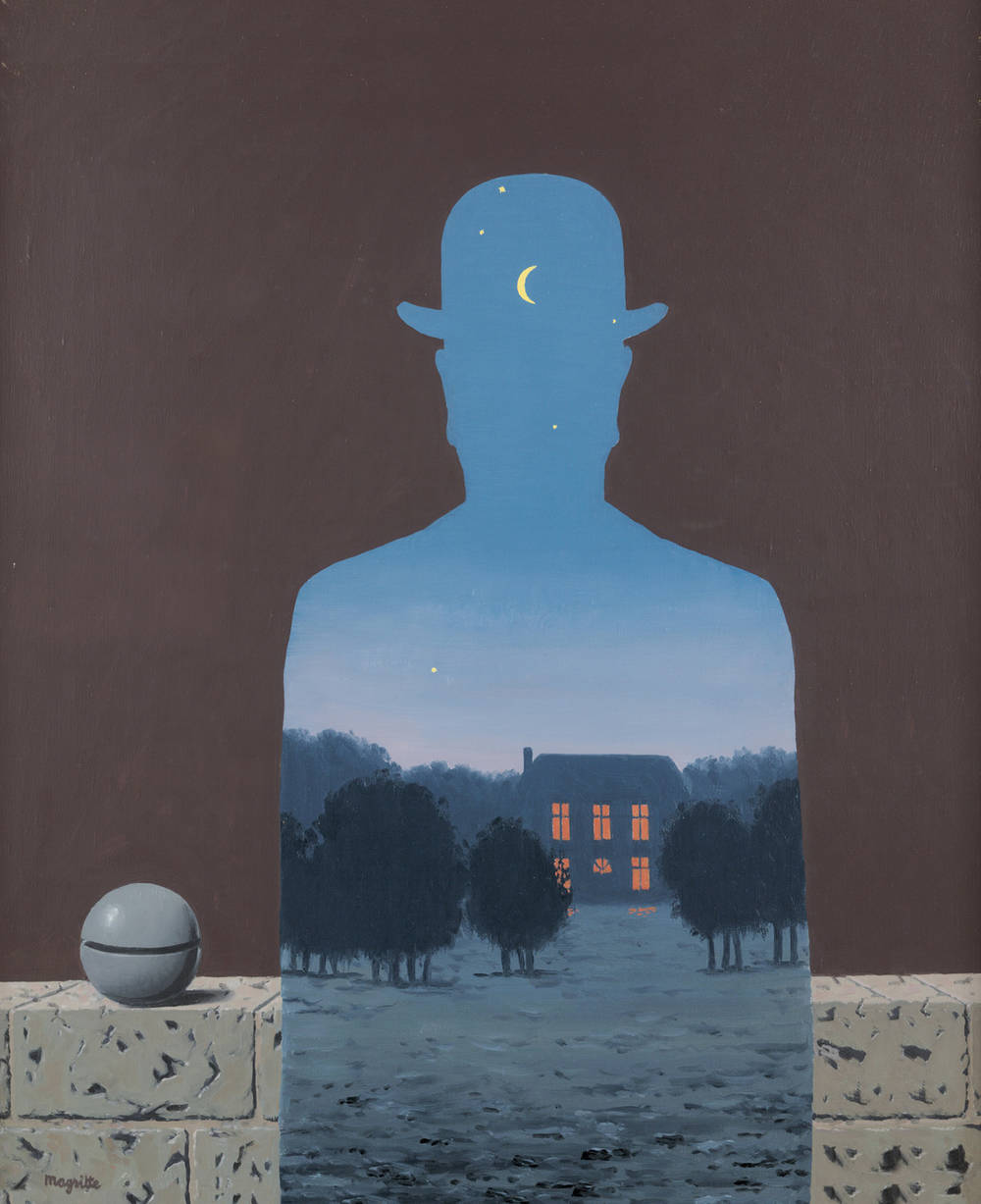

Inspired by the actions of the Parisian Surrealists, around the end of the 1920s a Surrealist group also developed in Brussels, centered around René Magritte. Yet the Belgians differentiated themselves from the French in certain crucial ways.

“SURREALISM, noun – Psychic automatism in its pure state, by which one proposes to express – verbally, by means of the written word, or in any other manner – the actual functioning of thought. Dictated by thought, in the absence of any control exercised by reason, exempt from any aesthetic or moral concern.”

This is how André Breton defined the movement he had founded with some of his artist friends in his 1924 “Manifesto of Surrealism.” Their aim was to distance themselves from the satirical actions of the Dadaists with a new definition of art and to trigger a “surrealist revolution.” Hence this was the name given to the journal that André Breton, Pierre Naville and Benjamin Péret published from 1924 onwards.

A fascination for puzzling symbols

Plain and harmless on the surface, the texts and drawings in the magazine dealt, amongst other things, with the depths of the psyche, with violence, sexuality and suicide. After all, the Parisian Surrealists were fascinated by the secrets of the subconscious, and there was great enthusiasm for Sigmund Freud’s “interpretation of dreams” and its explanation of puzzling symbols.

They used techniques such as automatic writing and painting in order to bring what was hidden inside to the fore – an approach the Surrealists believed would lead to the resolution of all problems: “Surrealism is based on the belief in the superior reality of certain forms of previously neglected associations, in the omnipotence of the dream, in the disinterested play of thought. It tends to ruin once and for all all other psychic mechanisms and to substitute itself for them in solving all the principal problems of life,” Breton went on to say in his Manifesto. He claimed a belief “in the future resolution of these two states, dream and reality, which are seemingly so contradictory, into a kind of absolute reality, a surreality, if one may so speak.”

The dream as a mirror of the subconscious

In Belgium they took a different view. Shortly after the publication of Breton’s writings in Paris in 1924, the Belgian writers Paul Nougé, Camille Goemans and Marcel Lecomte got to work compiling “Correspondence,” initially published as a total of 22 pamphlets distributed to the public – which in this instance primarily comprised poets and fine artists – at intervals of ten days. Some of the writings found their way into the circles of Parisian Surrealists, where they were met with a frosty sort of respect – the relationship between the artists in Brussels and those in Paris was permanently characterized by this mixture of tension and high regard.

This was, not least, down to the fact that those in Brussels had little regard for the “omnipotence of the dream,” as preached by Breton. One “Correspondence” contains a text against the perception of the dream as a subconscious source to which one has unhindered access; because when you attempt to communicate this dream you inevitably hark back to the words or the image, something that happens perhaps not “directly,” but in an organized way.

A bottle is a bottle and not a womb

Those in Paris were convinced that not only did they have to first consider their dreams carefully, but also implement them directly and in refined form in an image or a text – but the Belgians viewed this with some skepticism. Magritte too rejected the description of his paintings as ‘dreamlike’: “The word ‘dream’ is often misused concerning my painting. My works are not oneiric, on the contrary. If ‘dreams’ are concerned with this context, they are very different from those we have whilst sleeping. It is a question of self-willed ‘dreams’ in which nothing is as vague as those feelings one has when escaping into dreams. Dreams that are not intended to make you sleep, but to wake you up,” he is quoted as saying – and this despite the fact that one appears to come across symbols and stories from the subconscious in his very paintings. Yet the smart man with the bowler hat had little time for overly imaginative interpretations of his images: “In my painting a bird is a bird. And a bottle is a bottle, not a symbol of a womb.”

André Breton, 1924/1929. [Public domain or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

René Magritte took to the stage of Belgian Surrealism in 1926 when he published texts and illustrations in the critical Surrealist art magazine “Marie” published by the writer E.L.T Mesens, and in doing so broke away from Dadaism once and for all. “Marie” initially appeared as competition to the “Correspondence,” but Nougé and Magritte quickly became friends and in 1928 founded the publication “Distances” – thus becoming the mouthpiece of the Brussels-based movement. Like Magritte, Nougé also rejected automatic writing and was more interested in the coming together of word and image. Many titles of Magritte’s works come from Nougé’s pen.

Magritte in Paris

Although in hindsight René Magritte’s Surrealist paintings slot perfectly into the pictorial worlds of the Parisian Surrealists, it wasn’t easy for the Belgian to gain access to Breton’s circle. And although Breton overwhelmed Magritte with all manner of tasks one had to fulfil without resistance in the circle of the Surrealists, he neither urged him to sign important tractates with other artists nor did he mention him in his book “Surrealism and Painting,” published in 1928.

René and Georgette Magritte, a bourgeois, married and scandal-free couple, appeared suspicious to the Surrealists, who were known for their extravagant lifestyle. It was only in 1929 (Magritte and his wife had been living in Paris for two years and Magritte had already painted over 100 new pictures) that he wrote the article “Le mots et les image” (“Words and images”), which was published in the group’s own publication “The Surrealist Revolution.” André Breton and René Magritte were respectful of each other – Breton even purchased one of Magritte’s paintings – but friends they were not.

A little less excess

He couldn’t take seriously someone who had no time for music, fulminated Magritte, after Breton had labelled the art form ‘snobbish.’ Whereas in Paris the Surrealists rebelled against the bourgeoisie, despised music and sought to plumb the dark depths of the soul, in Brussels they cultivated a rather more playful, less revolutionary and less excessive surrealism, with the aim of “casting doubt on reality through reality itself.” All the while armed with an umbrella, charm and a bowler hat.

How Hip Hop sings about its dead

Death plays a large part in Hip Hop. The tragic early passing of legends such as Biggie Smalls and Tupac, not to mention rising superstars like...

5 questions for Mary Messhausen and proddy produzentin

With the performance "Thonk piece: Hungry for Stains", drag queens Mary Messhausen and proddy produzentin will open the exhibition COSIMA VON BONIN....

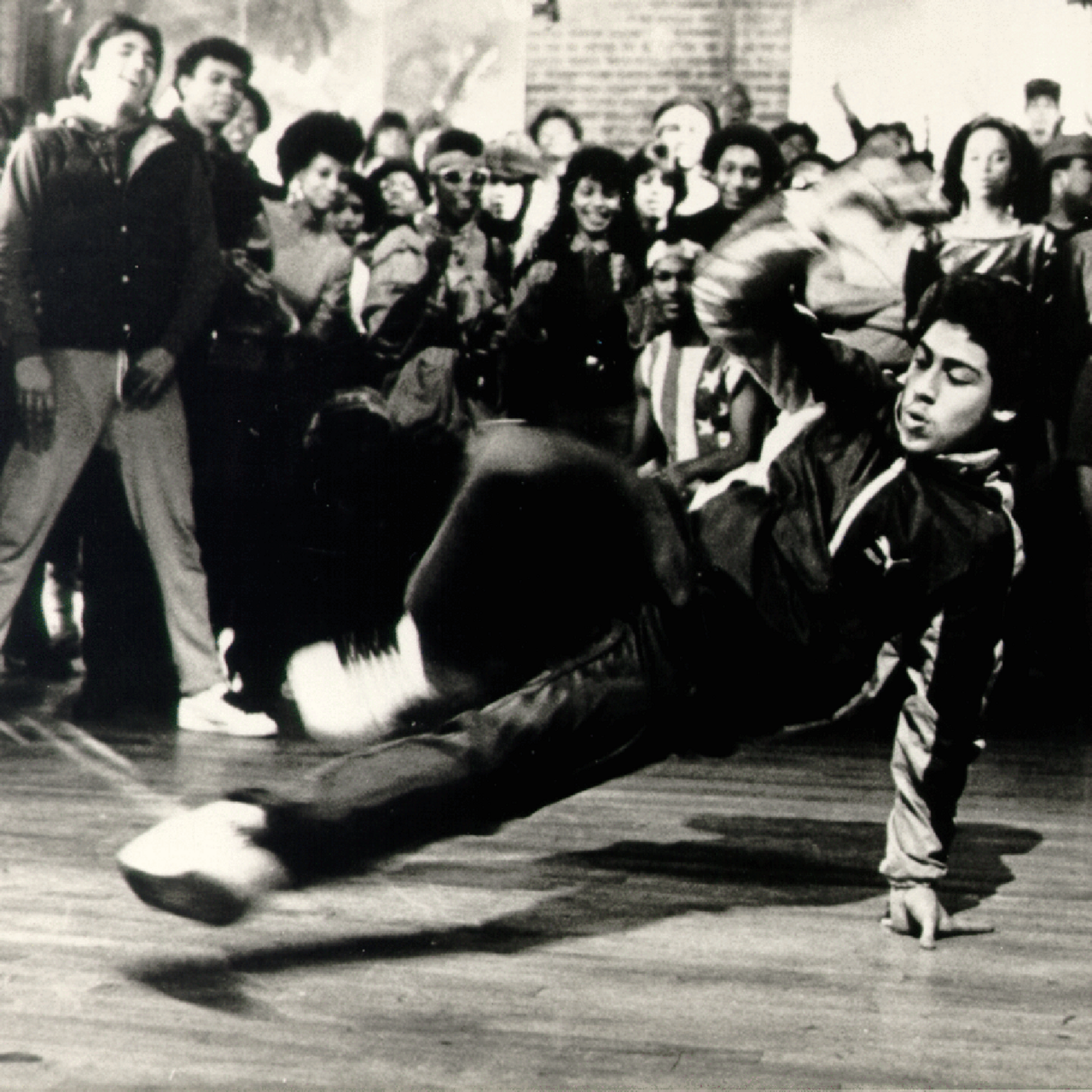

HIP HOP IS BLACK CULTURE – NOT THE OTHER WAY AROUND

Hip hop’s 50th birthday is an occasion for us to listen to some old records and mixed tapes and to look back at the most important hip hop films of...

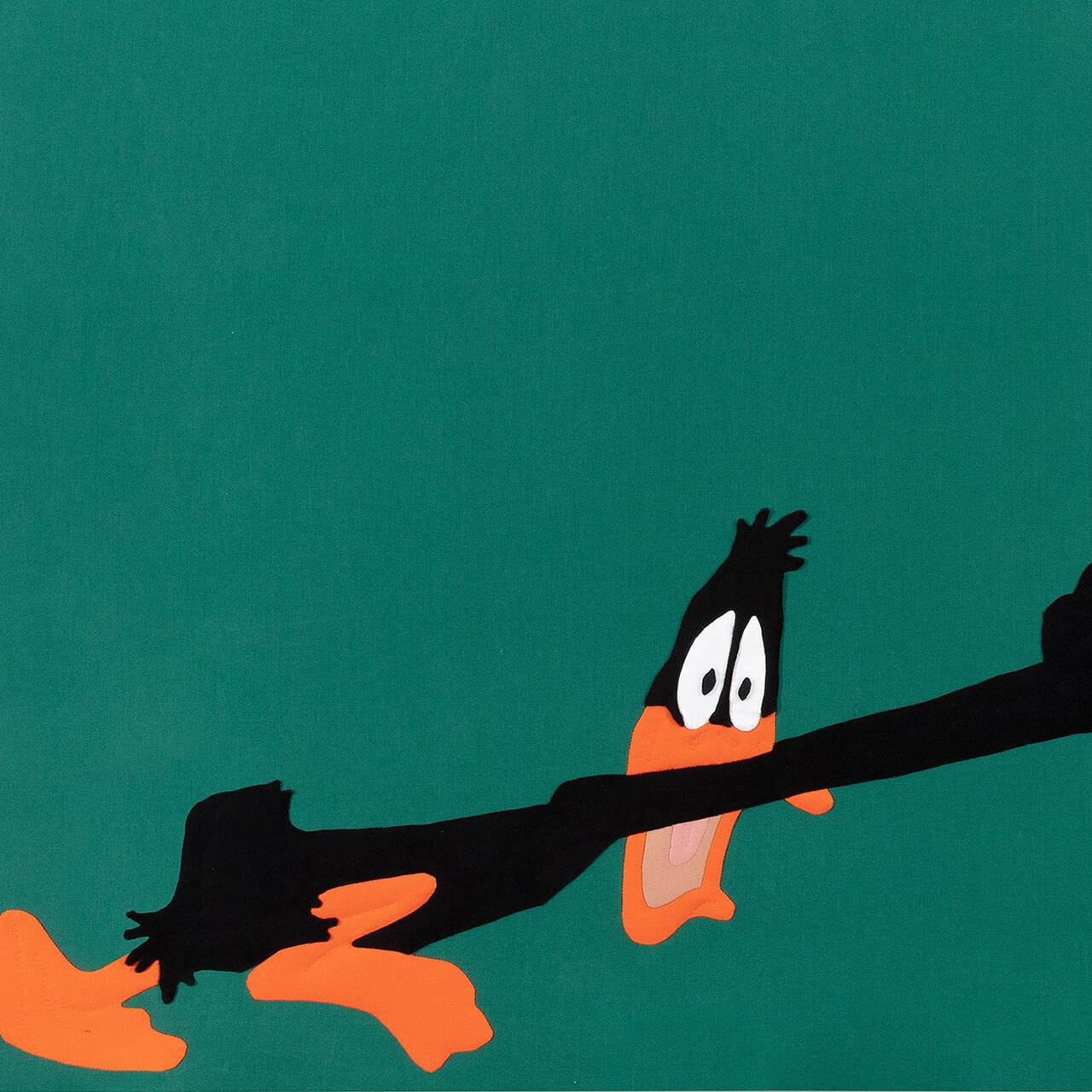

Now at the SCHIRN:COSIMA VON BONIN

The SCHIRN is showing a unique presentation of new and well-known works by COSIMA VON BONIN until June 9.

You Get the Picture: On Movement and Substitution in the Work of Lena Henke

The artist LENA HENKE already exhibited in the SCHIRN Rotunda in 2017. What are the secrets of her practice and where can you find her art today?

SHALLOW LAKES – plumbing the depths

In the SCHIRN’s rotunda, MELIKE KARA is presenting a series of sculptures that are reminiscent of bodies of water or small lakes. So, what’s this...

When subculture becomes mainstream – a balancing act

Regardless of whether it is hip hop, techno, or the queer scene: It is not unusual for the aesthetics of countercultures and subcultures to morph into...

Now at the SCHIRN: THE CULTURE: HIP HOP AND CONTEMPORARY ART IN THE 21ST CENTURY

Coinciding with the 50th anniversary of the birth of hip hop, the SCHIRN dedicates a major interdisciplinary exhibition to hip hop’s profound...

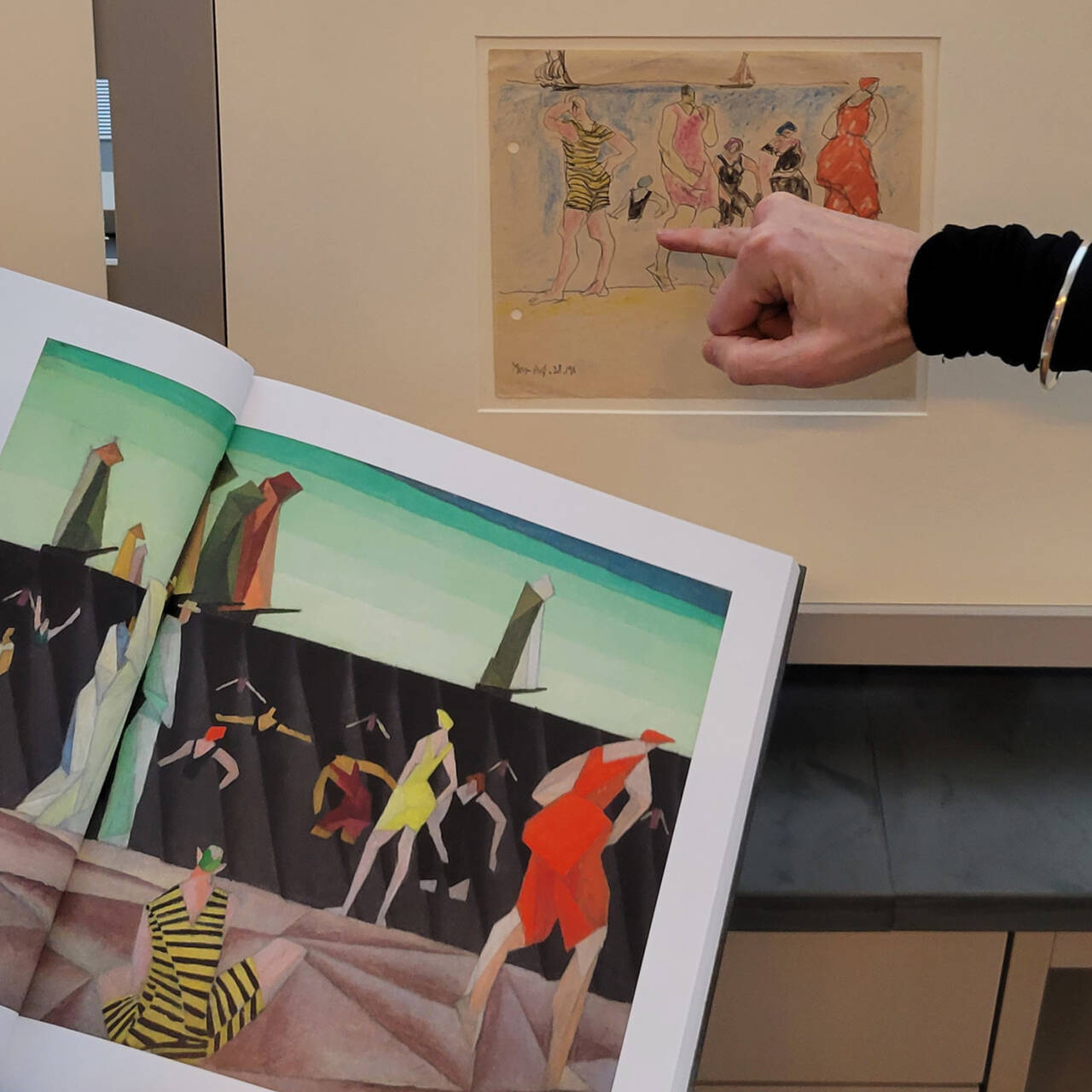

Julia Feininger – Artist, Caricaturist, and Manager

Art historians can tell us a lot about LYONEL FEININGER, but who was Julia Feininger and what legacy did she bequeath to the world of art?

Lyonel Feininger and the Harvard Art Museums. Part 2

The Harvard Art Museums host the largest Lyonel Feininger collection in the world. The directors Lynette Roth and Laura Muir chat about Feininger’s...