How can we understand the phenomenon that is René Magritte? The artist’s collected writings are brimming with dreams, conversations, biographical anecdotes and artistic treatises that say a great deal about him.

Political pamphlets, artists’ manifestos, autobiographical notes, excerpts from letters, scripts, interview questions and answers, unfinished thoughts and parts of conversations: The collected writings of René Magritte span a period of more than 40 years and have at least as many facets as his paintings – and are just as enigmatic.

They cause confusion, make us stop and think, are provocative, repulsive, inspiring and astonishing all at once: “He was proud to eat his sandwich”, is the first sentence of a portfolio that Magritte attempted to write, but may never have completed; a flyer from 1958 is entitled “René Magritte questions the living stones” and under the heading “Thoughts not thought” we read in true Magritte-esque style: “I have never thought this.”

A fundamental distrust of art

Throughout his entire life, Magritte was occupied with the question of what mission an artist should pursue and which liberties he can allow himself in the creation of his works. Even looking back, he, who at times preferred to work as a commercial artist than subject his art to the fancy of some patron or other, did not consider himself part of the art scene: “As for the artists themselves, most of them happily gave up their freedom and put their art in the service of someone or something. Their worries and ambitions are generally the same as those of the next-best careerist. Thus I acquired a thorough distrust of art and artists, whether they were officially recognized as such or aspired to be, and I sensed that I had nothing in common with this guild.”

Magritte did not seek to please someone or other, but pursued a higher aim with his paintings. He sought to make familiar and everyday objects like a chair, an apple or a pipe “shriek aloud,” to question and mix up the natural order of things. The Surrealist movement provided something like a huge playground for these kinds of experiments, indeed, “Surrealism calls for a freedom for waking life that resembles the one we have when dreaming,” as we read in his notes. One text is also entitled “Surrealist Games”; short sentences that read like stage directions and call to mind Luis Bunuel’s mysterious short film “An Andalusian Dog.”

Psychoanalysis and the mystery of the world

Yet for all his affiliation with Surrealist circles, it is also clear from his writings that Magritte doubted the demands and means above all of the Parisian group around André Breton, and first and foremost the oft-praised psychoanalysis: “Art, as I understand it, defies psychoanalysis […] I take care to only paint pictures that evoke the mystery of the world. […] No sensible man believes that psychoanalysis could explain the mystery of the world.”

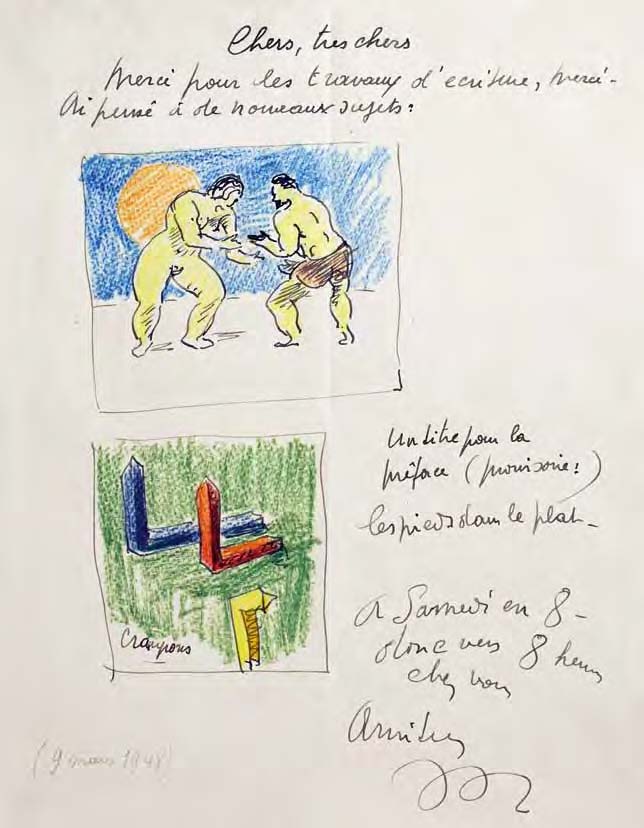

Letter by René Magritte of 1944, Image via sothebys.com

Magritte, the doubter: doubter of the symbolism and interpretability of common objects and of the immutable connection between things and their designations, doubter of established human thought and viewing patterns. It becomes apparent in his writings that these doubts fueled his creative output, his paintings; always with the goal of wakening observers from their habitual sleep and making them aware that behind every object is another object – whether visible or not.

5 questions for Mary Messhausen and proddy produzentin

With the performance "Thonk piece: Hungry for Stains", drag queens Mary Messhausen and proddy produzentin will open the exhibition COSIMA VON BONIN....

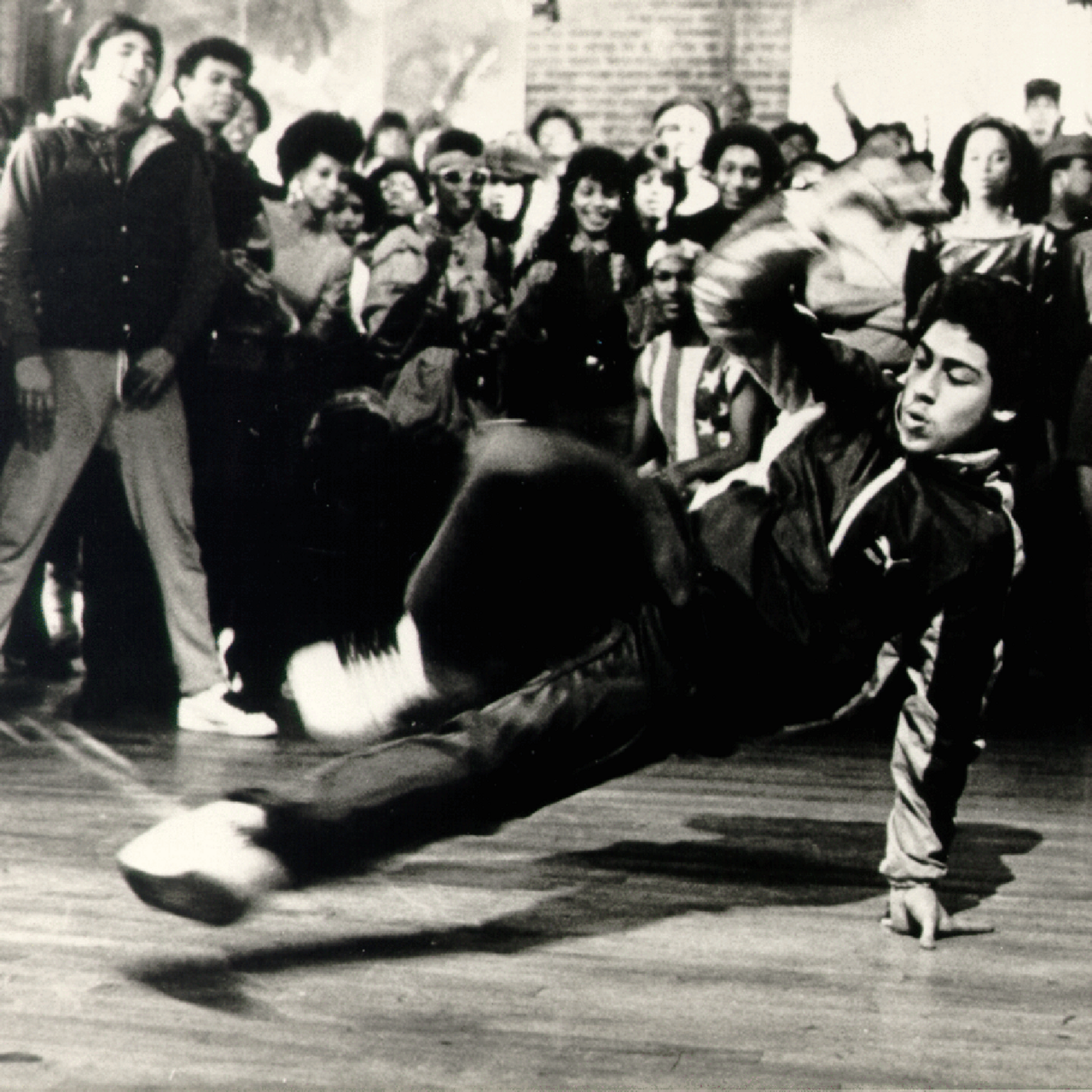

HIP HOP IS BLACK CULTURE – NOT THE OTHER WAY AROUND

Hip hop’s 50th birthday is an occasion for us to listen to some old records and mixed tapes and to look back at the most important hip hop films of...

Now at the SCHIRN:COSIMA VON BONIN

The SCHIRN is showing a unique presentation of new and well-known works by COSIMA VON BONIN until June 9.

You Get the Picture: On Movement and Substitution in the Work of Lena Henke

The artist LENA HENKE already exhibited in the SCHIRN Rotunda in 2017. What are the secrets of her practice and where can you find her art today?

SHALLOW LAKES – plumbing the depths

In the SCHIRN’s rotunda, MELIKE KARA is presenting a series of sculptures that are reminiscent of bodies of water or small lakes. So, what’s this...

Ukrainian art in Frankfurt - When anatomy becomes political

The art of Ukrainian artist Vlada Ralko gets under your skin - quite literally. At the heart of her drawings and large-scale paintings lies the human...

When subculture becomes mainstream – a balancing act

Regardless of whether it is hip hop, techno, or the queer scene: It is not unusual for the aesthetics of countercultures and subcultures to morph into...

Now at the SCHIRN: THE CULTURE: HIP HOP AND CONTEMPORARY ART IN THE 21ST CENTURY

Coinciding with the 50th anniversary of the birth of hip hop, the SCHIRN dedicates a major interdisciplinary exhibition to hip hop’s profound...

Julia Feininger – Artist, Caricaturist, and Manager

Art historians can tell us a lot about LYONEL FEININGER, but who was Julia Feininger and what legacy did she bequeath to the world of art?

Lyonel Feininger and the Harvard Art Museums. Part 2

The Harvard Art Museums host the largest Lyonel Feininger collection in the world. The directors Lynette Roth and Laura Muir chat about Feininger’s...