With the help of traditional ceramic techniques, the painter Joan Miró created murals of huge dimensions all over the world. One of the biggest ceramic walls is located in Ludwigshafen.

When, towards the end of his life, Miró was asked what he thought of the permanent inundation of our everyday lives by the modern media he responded:

If we do not attempt to discover the religious essence, the magic sense of things, we will do no more than add new sources of degradation to those already offered to people today, which are beyond number.

Here Miró invites us to take a refreshing step back, which is also something we are supposed to do when examining his work. Miró created an oeuvre that is better grasped through feeling than through logic and reason. It is not with a quick glance, but rather through meditative immersion that we can try to approach the essence of his art. This sensory component made his work suspicious to some in a time of increasing conceptualization of the arts.

Joan Miró on his house roof by Irving Penn, Spain, 1948, Image via theredlist.com

Furthermore, the thoroughly decorative nature of his work also met with rigid rejection amongst some art-lovers. We need only remember the attitude of art dealer Pierre Matisse, who dismissed the silhouettes of his father Henri Matisse as the childish gimmicks of an old man. Both of these however, the sensory and the decorative, were the ideal prerequisites to provide Miró’s art with an opening to the public sphere.

Gauguin, Matisse and Picasso

For his large-format murals Miró drew on crafts, which seems astonishing when, in the tradition of a modernism that perceptibly looked down on the “applied” arts, these were at best considered an “applied” art. Nevertheless, Miró had prominent forerunners here: Gauguin had already worked with artistic ceramics, and was later followed by Bonnard, Chagall, Derain, Max Ernst, Léger, Matisse and Picasso.

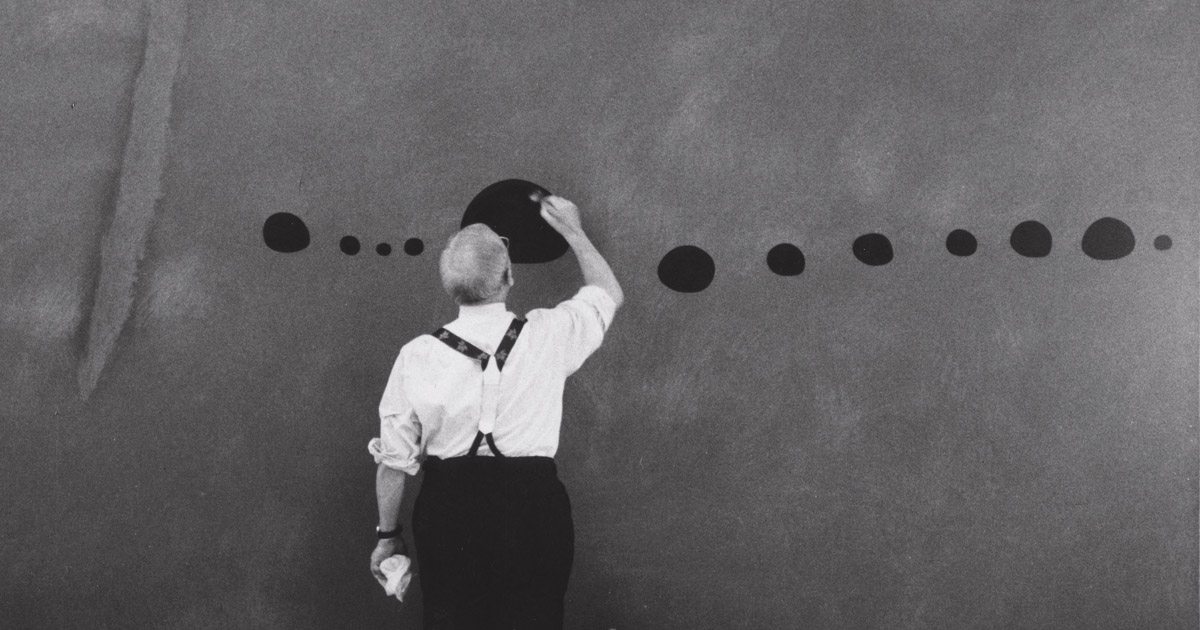

Joan Miró working on Oiseaux qui s'envolent by Francesc Català Roca, Gallifa, 1971, Image via theredlist.com

Today Markus Lüpertz and A. R. Penck also work on artistic ceramics. From 1944, the year in which his mother died, Miró began to create a total of 400 ceramic works and thus explored this field far more intensively than his fellow artists:

I was seduced by the splendor of ceramics: it is like a shower of sparks. And then the battle with the elements: with earth, fire (…). I am a definite fighter. If you make ceramics, then you need to be able to tame fire.

Initially he used a type of additive process to paint the vases and plates of his friend, Catalan ceramics master Josep Llorens Artigas (1892-1980), whom he knew from his time at art school in his native city of Barcelona. Between 1955 and 1979 he created a total of 14 ceramic murals, the execution of which also required the substantial involvement of Artigas’ son, Joan Gardy-Artigas (born 1938), who still runs his father’s workshop El Raco in the town of Gallifa to the northwest of Barcelona today.

Josep Llorens Artigas, Image via escolallorensartigas.com

The first two ceramic murals that Miró and Artigas created were the “Mur du Soleil”, the “Wall of the Sun”, and the “Mur de la Lune”, the “Wall of the Moon”. Miró and Artigas were among eleven representative artists, along with Picasso, Henry Moore and Alexander Calder, who were invited to create artworks for the Paris headquarters of UNESCO, then still under construction. These were supposed to live up to the claim of embodying the fundamental achievements of art at that time. Miró began the two murals in 1956 and as he did so drew inspiration from the cave paintings of Altamira, the Roman frescoes of Catalonia and mosaics by Gaudí.

The first tiles fail

Before his design was transferred to the ceramic, Miró created so-called “cartoons” in original size using charcoal and gouache. In earlier times cartoons were used, for example, for the creation of frescoes or tapestries. Thus, for example, Renaissance painter Rafael (1483-1520) created a series of now very famous cartoons with scenes from the history of salvation. These were placed under the threads for craftsmen to then weave the wall tapestries for the Sistine Chapel. Miró, who up to that point had barely worked in the monumental format, wanted to be sure of the impact of his work in advance.

Joan Miró, UNESCO Mural, Image via www.unesco.org

Miró subsequently transferred the drawing onto the tiles that lay on the floor. He painted using a brush made of palm fronds. The knowledge of the potter was essential in order to distribute the colors correctly, since these only become visible after firing (when applied, all the colors take the form of gray-black powder). The first uniformly sized square tiles failed, but afterwards everything went smoothly.

Impatient and tense

“Artigas held his breath when he saw how I held the brush and began to draw the five to six-meter-long design, at the risk of destroying work that had taken months. The final firing process took place on May 29, 1958. Thirty-four firing processes had gone before it. We had consumed 25 tons of wood, 4,000 kg of clay and 30 kg of coloring. Until then we had spread the work out on the floor in pieces only, and had no opportunity to step back and observe it as a whole. We waited, impatient and tense, to see the small and the large wall set up in the space and the light for which they had been made.”

The “Wall of the Sun” consists of 585 ceramic tiles and measures 2.2 x 15 meters. Set up parallel to it is the “Wall of the Moon”, which measures 2.2 x 7.5 meters. The Sun and Moon can be interpreted as day and night, life and death, whereby life has the upper hand here as the “Wall of the Sun” is twice as wide as the “Wall of the Moon”. The appeal of the ceramic walls comes from the contrast between the traditional technique and the modern art, the contrast between the rigidity of the fired clay and the playfully naïve strokes of a painting free of right angles, the contrast between colorful spontaneity and the strict design language of the concrete building.

President Eisenhower and Miró

The dynamics of the drawing, mere chance and the glowing color tones form fundamental design elements of the ceramic walls in Paris. Miró wanted to be there for the assembly of the tiles, and thus the Parisian building site became his second home for a time. The work was so well received that Miró was awarded a prize in 1959 that was presented to him personally by US President Dwight D. Eisenhower in the White House.

Facade of Hack-Museum, Ludwigshafen, Image via wikipedia.org

Later on Miró and Artigas would design murals that adorn walls from Barcelona to Zurich and from New York to Osaka. The nearest mural to the SCHIRN is located in the industrial town of Ludwigshafen, just 80 kilometers away. In 1979 the museum named after Cologne-based collector Wilhelm Hack was opened there, a typical concrete building of its day. Its 55-meter-wide and over 10-meter-high façade on its southeast side is covered entirely in a monumental painting made up of 7,200 stoneware tiles, which cost around 500,000 Deutschmarks at the time. The dynamic composition is an example of Miró’s later work and comes to life thanks to the sharp contrasts between the black drawing, the primary colors and a few green areas.

The lightness of the soul

One of Miró’s final creations is a wall ceramic of particularly poetic lightness, which adorns the harbor promenade of Palma de Mallorca. It is modeled on a painting from the year 1964, which Miró created for his then 4 and 5-year-old grandchildren with the aim of comforting them by showing them that their father, whom they had recently lost, had passed on into eternity and would protect them wherever they were. There is nothing of this infinitely sad loss in the work. Rather, it radiates a lightness that lifts the soul.

Wall ceramic by Joan Mió at the harbour promenade at Palma de Mallorca, Image via wikimedia.org

The Catalan of Paris

Joan Miró’s younger years were defined by his conservative family home – that is until he broke away and sought freedom, which he ultimately would...

The artist and the War

The Civil War, Franco’s dictatorship and fascism all had a significant influence on Joan Miró’s work. The painter made no secret of the fact that his...

Barcelona, the home of Joan Miró

It was in the Catalan metropolis of Barcelona that Miró was born, and it was here too that he took his first steps as an artist. Anyone visiting the...

It is difficult to be Miró’s grandson

Joan Punyet Miró, grandson of Joan Miró, in conversation about the famous grandfather. On SCHIRN MAGAZINE