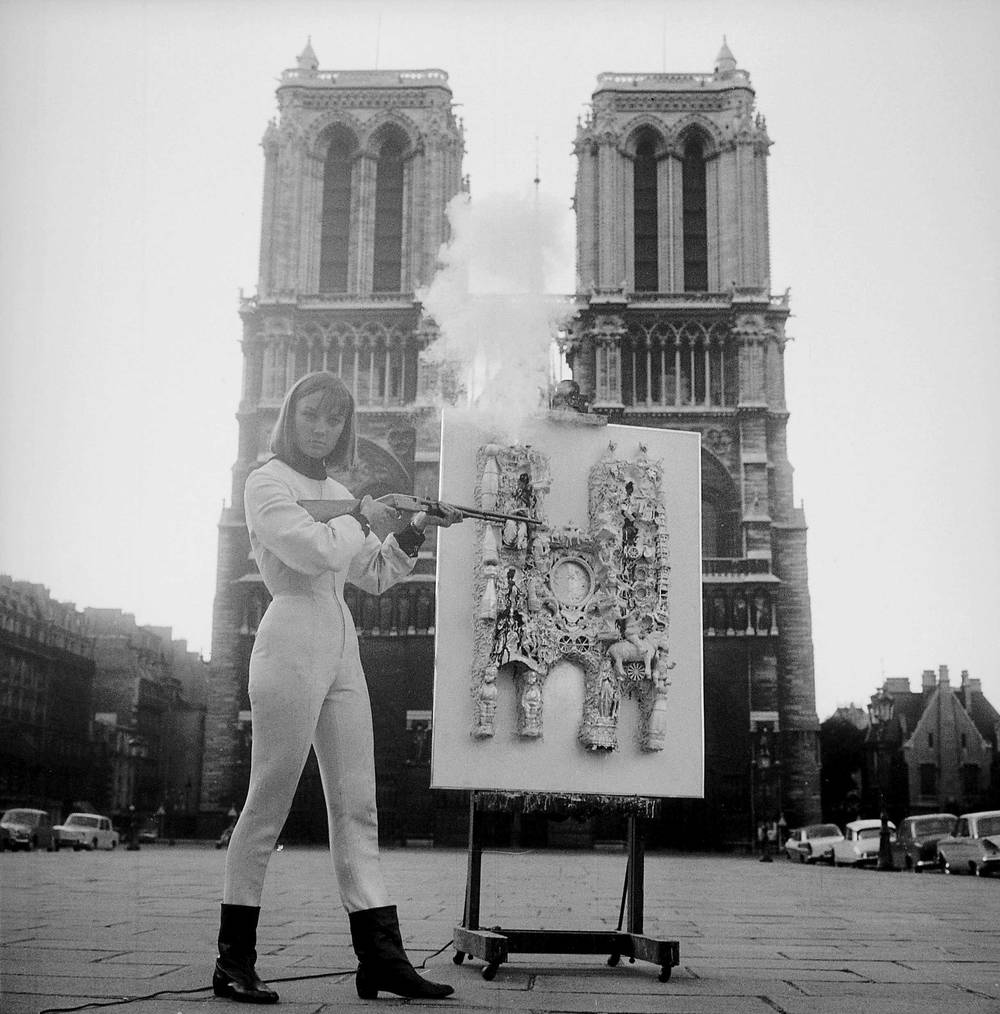

The “shooting paintings” made Niki de Saint Phalle famous overnight. So where did these spectacular acts of shooting actually take place? We cast a glance at the “crime scenes” where these creative acts of destruction took place.

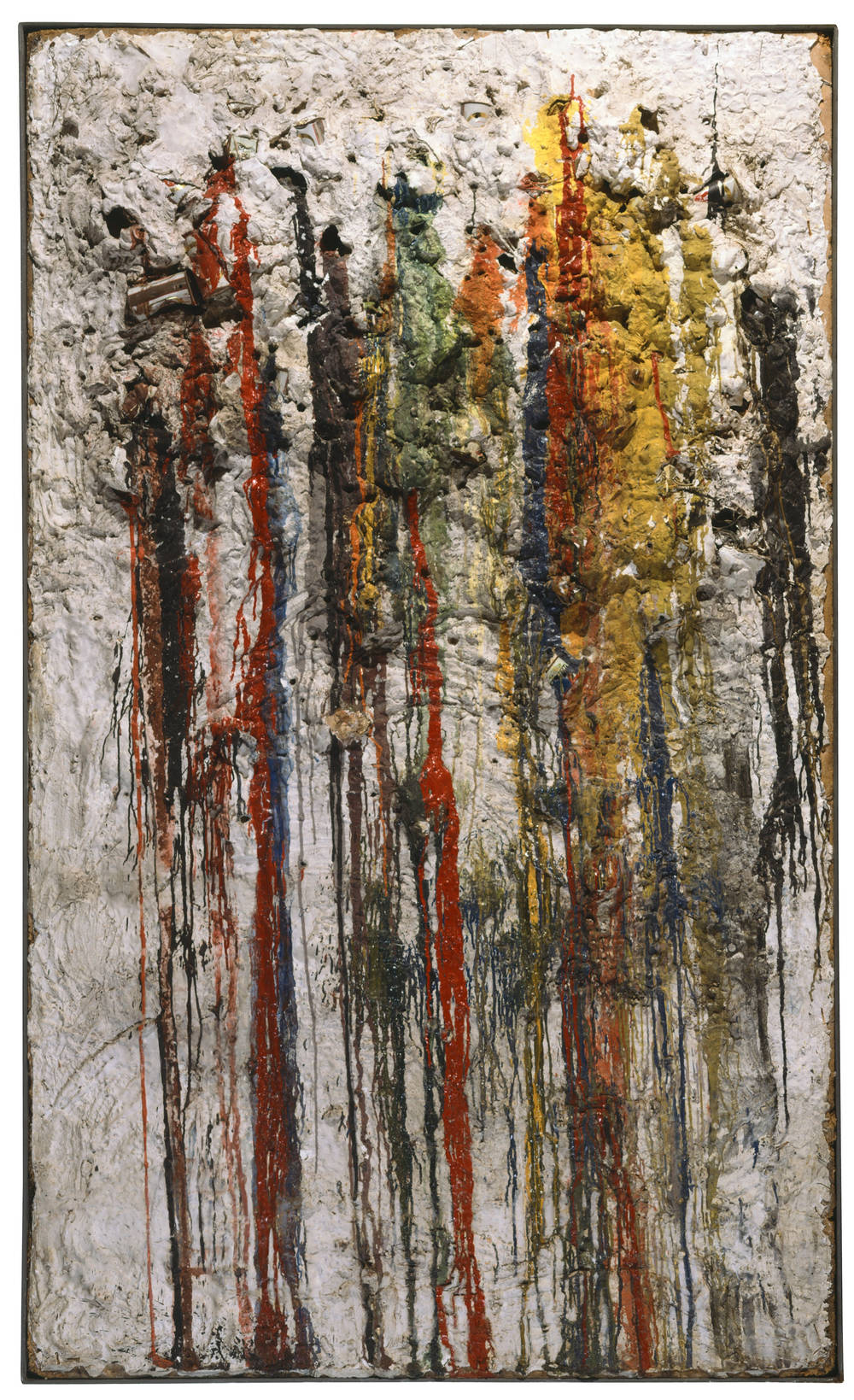

What is that anyway, a “shooting painting”? The “shooting paintings” (French: “Tirs”) are assemblages of objects that are mounted on wood or are freestanding and which Niki de Saint Phalle covered with a layer of white plaster. Among these objects she also included bags filled with liquid paint, as well as spray cans. The artist then blasted these initially pristine white works with firearms. The hidden reservoirs of paint exploded, and the colorful paint splattered, dripped, and poured across the works.

These works continue to enthrall audiences to this day. This is probably attributable to their radicality, but also the fact that they are so open to interpretation. Interpretations often take a psychologizing slant, viewing the paintings as outlets for pent-up aggressions, as the rebellion of a strong female artist personality against the patriarchal society and its rigid gender roles. In various texts and remarks she made Niki de Saint Phalle herself fueled to such a reading. At the same time the paintings were interpreted as acts of violence or, in the spirit of Surrealism, as an expression of sexual ecstasy. Pierre Restany, chief theorist of the Nouveaux Réalistes, enthusiastically emphasized the “cloudburst-like” aspect of Saint Phalle’s work. The ambivalence between emancipatory gesture and artistic showmanship innate in these pieces was also rightly underscored, along with the explosive mix of creation, destruction, and. However, the many different “crime scenes” at which the acts themselves took place have so far received little attention. What can they tell us about the artist and her work?

Shots fired in the backyard – the Impasse Ronsin

The first documented acts of shooting took place in February 1961 in Paris. To be more precise: in a backyard in the Impasse Ronsin on Montparnasse. At first glance the location appears rather mundane: A relatively small open space hemmed in by a somewhat dilapidated back wall and a board fence. Yet this “crime scene” was certainly not just any old backyard. And neither was the Impasse Ronsin any old cul-de-sac, but in fact an epicenter of artistic life in Paris at the time. The Basel-based Museum Tinguely even dedicated an entire exhibition with the eye-catching title of “Murder, Love, and Art in the Heart of Paris” to the location. It familiarized visitors with the fact that the place gained notoriety in the early 20th century as the scene of a double murder before, some decades later, it became home to a lively artist colony. No less a figure than Constantin Brancusi worked here until his death in 1957 and it was also here that Jean Tinguely had his apartment and studio, which from 1960 onwards he shared with Niki de Saint Phalle. The backyard in question often served de Saint Phalle as a shooting range or open-air studio in subsequent years.

Postcard of Impasse Ronsin, end of 19th century, Image via tinguely.ch

Going Public – visiting museums and galleries

The first two actions were followed that very same year by a further 13 acts of shooting. Many formed part of exhibitions or festivals. This also made the “crime scenes” more visible to the public. Just a few weeks after the first shots were fired in the Impasse Ronsin, Niki de Saint Phalle visited the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. On the occasion of the exhibition “Bewogen Beweging” she carried out a shooting action there on March 12, 1961. This time, she chose the grassy bank of a canal or pond as the location. Removed from the bustle of metropolitan life, here she created five comparatively small paintings, one of which was round like a target. She attached the latter to a tree before the shooting began.

At the exhibition’s second stop at Moderna Museet in Stockholm she realized not one but two shooting actions. The first took place in a backyard on May 14, 1961. The aesthetic similarity of the location to Impasse Ronin may have been intentional, as the action was an enactment for Swedish television. Further actions for film would soon follow. For the second Stockholm action de Saint Phalle took a trip with friends to the island of Värmdö off the Stockholm coast, where she used a sand pit as her shooting range. One of the “Tirs” created there is on view in the SCHIRN exhibition. Safety considerations (the place was private grounds) presumably played an important role in her choice of location. In Sweden as in most European countries the possession and use of firearms is strictly regulated and does not fall within the scope of artistic freedom.

Up until that point the shooting actions had taken place in a relatively private context. Soon however, de Saint Phalle expanded the visibility and scope of her actions. A particularly curious “crime scene” for a shooting action carried out on June 10, 1961, was the auditorium of the American embassy in Paris. Niki de Saint Phalle and Jean Tinguely had been invited to participate in a performance of “Variations II” (1961) by John Cage. While avant-garde musician David Tudor provided the musical part, visual artists – including Robert Rauschenberg – showed their work on stage. Niki de Saint Phalle caused a stir with a “shooting painting”. It is said that due to the safety concerns for the viewers, the services of a sharpshooter had to be engaged. The resulting piece is now part of the MoMA collection.

It was at about the same time that Niki de Saint Phalle prepared her first gallery exhibition. She developed a new series of works for it which she called the “Old Masters”. These are small format “shooting paintings” in opulent gold frames. The exhibition with the title “Feu à volonté” (English: open fire) was held at Galerie J, a small avant-garde gallery whose premises were located in a former motorcycle garage at 8 Rue de Montfaucon. The first shooting action open to the public too place here on the occasion of the opening on June 30, 1961. Jean Tinguely had designed a shooting booth of sorts especially for the action in order to ensure the safety of the visitors.

Invitation to the exhibition, Gallery J, Paris, June 30 - July 12. 1961, Image via stsenzatitolo.com

On the other side of the Pond – shooting actions in California and New York

News of the shooting female artist evidently spread like wildfire. It was not long before Niki de Saint Phalle was invited to show her work in the US, too. In March 1962, with the support of local galleries she staged her first shooting action in Los Angeles. This time, the “crime scene” was a parking lot located on a side alley and belonging to the Renaissance Club, a Jazz club on Sunset Boulevard. From this point onwards, Niki de Saint Phalle always wore her iconic white shooting suit for the occasion. This made her appear like a mix between a supermodel and a superhero. A photograph shows her standing on a ladder in this suit, aiming a rifle at an enormous tableau. The background shows the typical backyard walls of American timber houses. Perhaps it is the proximity to Hollywood that causes the location to appear like the film set of a Surreal gangster movie.

Image via telegraph.co.uk

A second action that took place just a few days later in glorious sunshine in the Malibu Hills, a residential and recreational district for the rich and beautiful, appears similarly staged but now reflects Hollywood’s glamorous side.

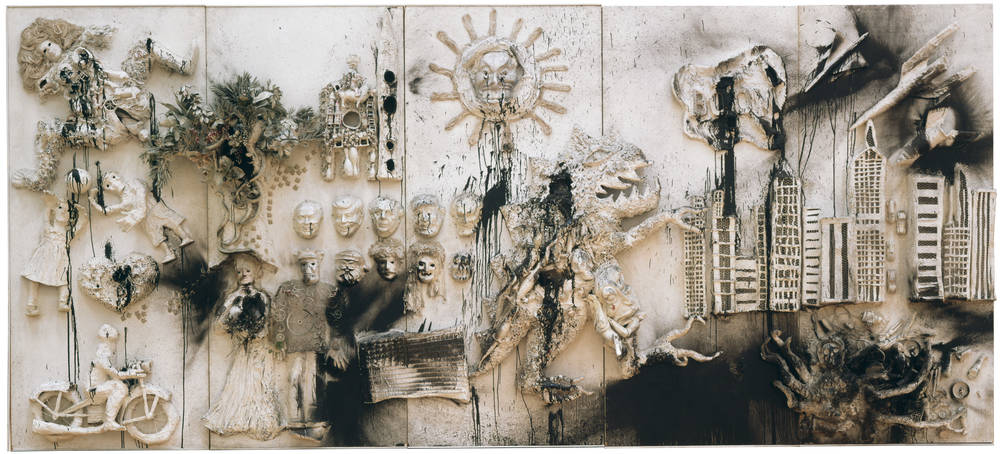

From California, and together with Tinguely de Saint Phalle travelled back to the East Coast. In New York, she produced her monumental work “Gorgo in New York” (1962). It is said to have been created in the legendary Chelsea Hotel frequented by the artistic avant-garde of the 1960s. Niki de Saint Phalle and Tinguely lived and worked there on several occasions when staying in New York. “Gorgo in New York” is one of several paintings that show American skyscrapers being attacked by one or more monsters. According to the artist, the theme arose on the one hand from her fondness for horror films and, on the other, from her preoccupation with the darker side of the American Dream and the omnipresent nuclear threat associated with the Cold War. The piece “King Kong” (1963), which is on display at the SCHIRN, draws on a very similar visual language. It was also created in the US, albeit in a Los Angeles studio for a solo exhibition at Dwan Gallery.

Niki de Saint Phalle's shoot in Malibu Hills, April 1962: pre-shoot picnic organized by Jane Fonda for John Houseman, photo:Niki de Saint Phalle, Image via dazeddigital.com

The era of the “shooting paintings” came to an end in 1964. It was not until 1970 that de Saint Phalle returned to the group of works one more time. The occasion for this was the major 10th anniversary festival held for the Nouveaux Réalistes in Milan. The spectacle presumably took place on Milan’s Piazza del Duomo. A photograph shows the artist – apparently after nightfall – aiming a rifle at a brightly lit “Tir” in the shape of a large altar. The large crowd watching in the background are kept safely at a distance by Italian carabinieri. In this instance, Niki de Saint Phalle did not don her white shooting suit but a black suit with white cuffs and a large cross around the neck. This get-up makes her look as though she were ceremoniously laying her “shooting paintings” to rest – in order to from then on devote herself to other works and new artistic strategies.

Niki de Saint Phalle, November 25.,1970, Image via pinterest.com

Secret backyard murder or staged art-execution?

What function did the “crime scenes” fulfill and what do they tell us of the “shooting paintings”? Mostly they were essentially remote spots – backyards, parking lots, or out in nature. However, sometimes they were also art institutions such as galleries, museums and even theater stages. Altogether these places can be classified as one of two types: The first, which include the Impasse Ronsin or the Chelsea Hotel, amounted to a private studio setting and served to prepare works for exhibitions. The others, which included the sand pit near Stockholm, the parking lot in Los Angeles, or the auditorium at the American embassy in Paris were by contrast action sites for public performances.

The shooting actions then turn out to only be a site-specific practice to a certain extent. The “shooting paintings” were created where the opportunity arose. We can only occasionally make out a direct connection between the places where they arose or the content of the works, for example with “Gorgo in New York” or the altar in front of the Cathedral of Milan. The “Old Masters”-series also appears predestined for a gallery exhibition. In the larger assemblages references to the place of creation seem to exist on the level of the everyday objects integrated into them. Nevertheless, in most shooting actions the choice of location appears to have been dependent primarily on pragmatic considerations, which included not only the proximity to the host institution but also legal issues and, above all, public safety.

Looking at the works created in this way today, the explosive paint marks and perforations bear witness to the intensity of the actions that brought them about. They evoke the bang of the gunshots and the violent penetration of the cartridge into the surface of the work, which can almost be experienced as physical pain. In order to feel this intensity it is not imperative to know the contexts in which they were created. However, a look at the “crime scenes” can show that the actions were not quite so spontaneous and “cloudburst-like”. Rather, they were carefully planned and staged events. They were acts of art creation that were equally controlled and rebellious, carried out in close symbiosis with the art world of their time, yet remarkably idiosyncratic.