With her radical “shooting paintings” Niki de Saint Phalle took the art world by storm. However, seldom did she realize these works on her own. Who helped her? We cast a glance at her networks in the art scene and the accomplices behind the shooting actions.

Although they are not among the earliest works Niki de Saint Phalle made, there is a Big Bang aspect to the “shooting paintings” (French: “Tirs”) in the context of her complete oeuvre. After all, they made the artist famous overnight. As such it’s not surprising that the SCHIRN exhibition begins with an insight into this body of works created between 1961 and 1964.

The “shooting paintings” are assemblages of objects that Saint Phalle blasted apart using firearms. This made the hidden reservoirs of paint explode, which then splattered and poured across the works. In art historical terms the works can be read as conceptual paintings and precursors of the happenings and performance art. They are an expression of the complex blurring of the boundaries in art at that time. It was a time when groups of artists like the French Nouveaux Réalistes, whose only female member was de Saint Phalle, were working on reuniting art and the reality of life. One aspect of this hinged on the view that works of art should no longer be revered as the brilliant creations of lone artistic geniuses but should become visible as an integral part of reality. Thus, a new role was assigned to one’s artistic environment and the public with the latter sometimes being directly involved in the process of creation. This was also the case for the “shooting paintings” that were often the result of collaborative processes. So, who were Niki de Saint Phalle’s accomplices who then joined her in committing radical “assaults” on art? And what do they tell us about the artist’s methods of working and networks?

In the Circle of the Nouveaux Réalistes

The first known shooting action took place on February 12, 1961 in a backyard of Impasse Ronsin in Paris. This was where Niki de Saint Phalle and Jean Tinguely, her partner in art as in life, had their studio. A photograph of the action shows a small group of people. In the foreground a man in a black coat aims a pistol at a work of art that is not visible in the picture. The shooter is none other than Pierre Restany, co-founder and “chief theorist” of the Nouveaux Réalistes. Behind him stand his then partner Jeannine de Goldschmidt, owner of Galerie J, and the artist Daniel Spoerri. The other people present were Jean Tinguely and the man who made then gun available, the operator of a rifle range. Harry Shunk took the photograph. He together with his partner János Kender, numbered among the most important chroniclers of the European and American avant-garde in art.

Niki de Saint Phalle and Jean Tinguely at Impasse Ronsin, 1962, photo: Vera Mercer; © Vera Mercer/courtesy °CLAIR Galerie, Image via tinguely.ch

Evidently, this action was neither spontaneous, nor was it public but was more of an insider event in the art world. Pierre Restany later recalled that Tinguely had invited him and Jeannine de Goldschmidt to the action. It would seem that Tinguely used his contacts so that de Saint Phalle was not only seen merely as his glamourous companion – as the daughter of a banker and “Vogue” cover girl she was already a familiar figure in the scene – but was also perceived as an artist to be taken seriously. And he was successful: Restany was thrilled with de Saint Phalle’s art, which in his eyes “breathed the authentic reality of its time to the full”. Without further ado he declared the artist a member of the Nouveaux Réalistes.

Here she was in excellent company. Members included Yves Klein and Daniel Spoerri, with whom she shared an interest in action painting and the medium of assemblage. That said, her most important artist collaborator and sparring partner remained Jean Tinguely. He was directly involved in the creation of almost all of the “shooting paintings”. He helped make the picture backings of wood, wire, objects and plaster. For the shooting of larger tableaus he built small cannons with various special effects in terms of the bang and/or the smoke. And for an exhibition in Jeannine de Goldschmidt’s Galerie J he designed a shooting range that the audience could fire from. Moreover, he took part in almost all the shooting actions, often actively as a shooter, but also as a passive onlooker.

A Lifelong Friendship – Pontus Hultén

Swedish museum professional and curator Pontus Hultén was above all important for the international spread of Niki de Saint Phalle’s works. The artist had met him back in 1959 and he became one of her most valued supporters. A few weeks after the first shots were fired at Impasse Ronsin, Hultén invited her to take part in his exhibition “Bewogen Beweging” in Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum. As the title suggests, the topic of the exhibition was Kinetic Art, in other words art in motion. In connection with this on March 12, 1961, she arranged a small shooting event, too. In addition to Hultén and Tinguely, others present included Niki de Saint Phalle’s sister Elisabeth, MoMA curator William Seitz, artist Per Olof Ultvedt, and photographer János Kender. As part of the second stage of the exhibition, which then took place under the title “Rörelske i konsten“ (Eng: Movement in Art) in Stockholm in Moderna Museet (Hultén was its director), two shooting actions were presented. One was organized for television, the other took place in a nearby sand pit. Artist Robert Rauschenberg who was himself involved in the exhibition and was currently in Europe also participated in this latter action.

Tinguely, de Saint Phalle and Rauschenberg,1961,Shunk-Kender © Roy Lichtenstein Foundation, Image via art-folio.ch

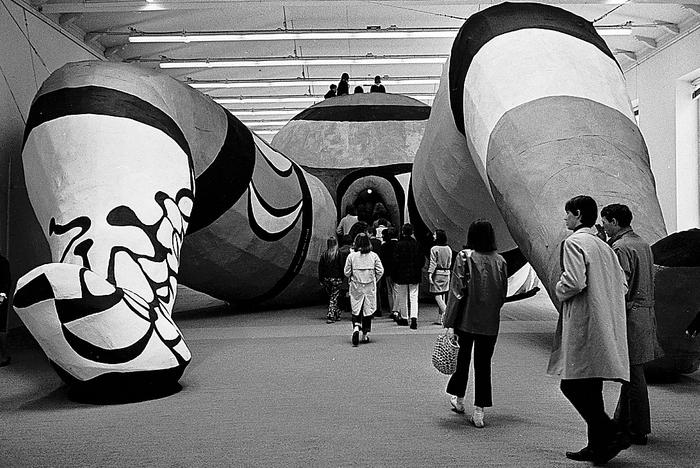

Back in Paris there was a renewed collaboration with Rauschenberg but also with the artist Jasper Johns – first as part of an experimental music performance in the theater of the American Embassy in Paris, during which a shooting painting was also created. As the two famous fellow artists from New York were now also in town, Niki de Saint Phalle had them shoot at two more of her pictures. While Rauschenberg fired wildly and shouted: “Red! Red! I want more red!” de Saint Phalle later remembered how Johns deliberated over the situation for several hours before completing the work assigned to him with a few precise shots. The resulting picture ended up in the private collection of Pontus Hultén, who donated it along with some 700 works by renowned artists to the Moderna Museet in 2005. Hultén continued to be an advocate of Niki de Saint Phalle long after her first artistic works. Apart from the exhibitions “DYLABY” (1962) (also with shooting actions) and Hon (1966), in the 1990s he also organized large retrospectives of her work and was actively involved in her catalog raisonée.

Niki de Saint Phalle, Hon en Katedral, 1966, photo: TT, Image via aftonbladet.se

Networks in the US Art Scene

On the back of the contacts she had made to the American art world in spring 1962, de Saint Phalle was invited to produce shooting actions in the United States. On March 4, 1962, she staged one such action in Los Angeles. The host was Everett Ellin Gallery, though it was gallerist Virginia Dwan who had acted as the go-between. Now the artist not only enjoyed the hands-on support of Jean Tinguely, but also of Ed Kienholz. The assemblage artist to whose oeuvre the SCHIRN devoted a major exhibition, became a close friend of the couple. As a passionate hunter and weapons enthusiast he was particularly taken by the “shooting paintings”. He also attended the second spectacular action in California, which took place in the pretty Malibu Hills and was sponsored by the Dwan Gallery. The event was extensively photographed and filmed. The film recording shows how Kienholz hands de Saint Phalle various firearms or in a paternalist gesture that would seem irritating today uses a handkerchief to wipe paint splatters from her face. Among the spectators – and there were about 30 of them in all – were all kinds of art and Hollywood celebrities including actors Jane Fonda and John Houseman, curator Henry Geldzahler, model Peggy Moffit and her husband photographer William Claxton, who had already taken photos of the shooting action in Los Angeles. Given that both benches and a picnic set were taken along it remains uncertain whether this illustrious company was simply wanting to enjoy art or a break from the glamorous daily routine of Hollywood – probably both.

Niki de Saint Phalles Shooting at the Malibu Hills, April 1962: Picnic before the shoot organized by Jane Fonda for John Houseman, photo:Niki de Saint Phalle, Image via dazeddigital.com

Photography as Accomplice

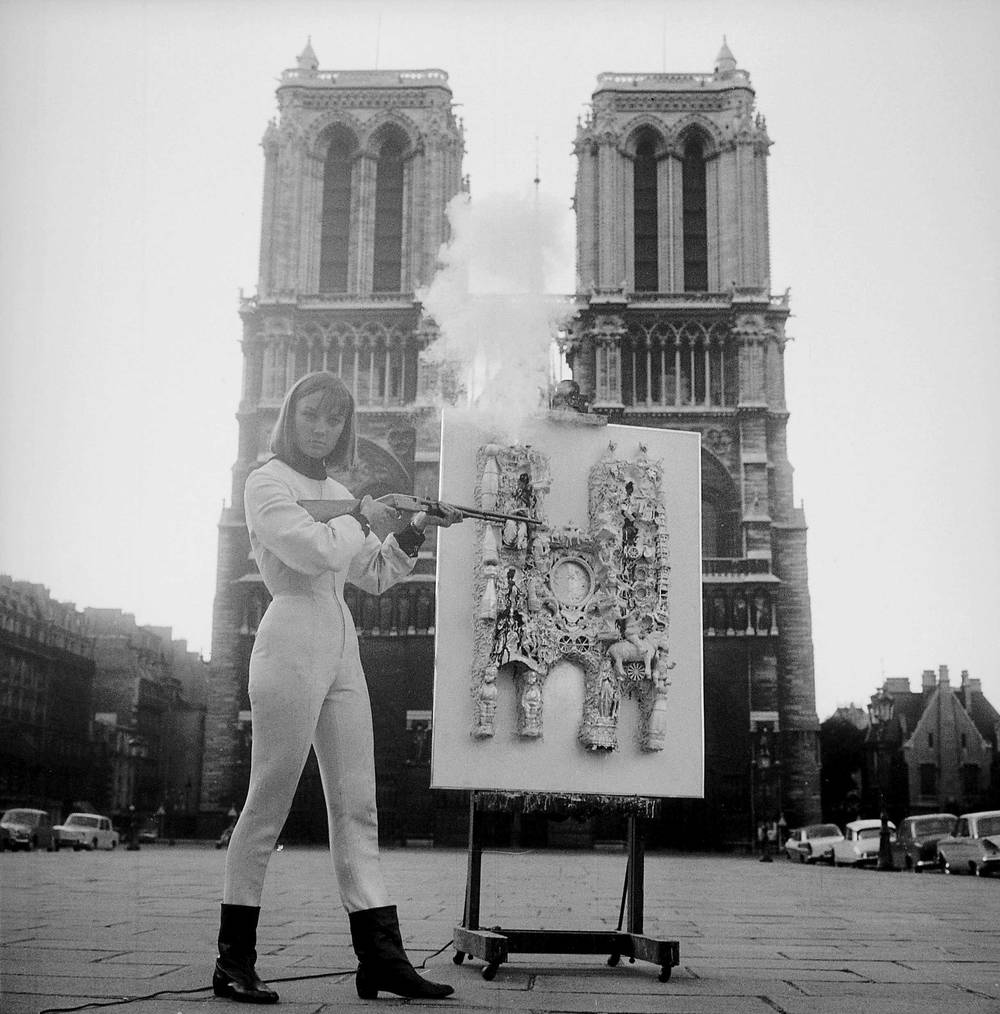

The shooting actions made for extremely attractive film and photographic themes. This is demonstrated by the almost inestimable amount of documentation material, recorded by some highly renowned photographers. Niki de Saint Phalle does not seem to have been at all averse to documenting her actions, on the contrary. The choice of locations and guests but also her striking costumes – from 1962 the artist wore her white, figure-hugging shooting suit – testify to a faible for dramatic presentation. This is especially the case for an action dating from 1963, in which there was probably no shooting at all – other than the shots by a camera. Pictures depict the artist in her shooting suit and brandishing a gun in front of Notre Dame in Paris. Next to her is a shooting picture on an easel from which wisps of smoke are rising. What at first sight looks like the documentation of a shooting action, proves on closer inspection to be a photomontage by Harry Shunk, who had already masterminded Yves Klein’s famous “Leap into the Void” (1960). In addition to illustrating de Saint Phalle’s delight in staging such shooting actions, the image once again clearly shows that photographers were among her most important allies. It was only through their images that the performative acts, which were so important for the creation of the “Tirs”, became visible for a wider audience. You might argue that photographers could be said to become co-authors of her works.

“Handing Over” the Shooting Paintings to the Public

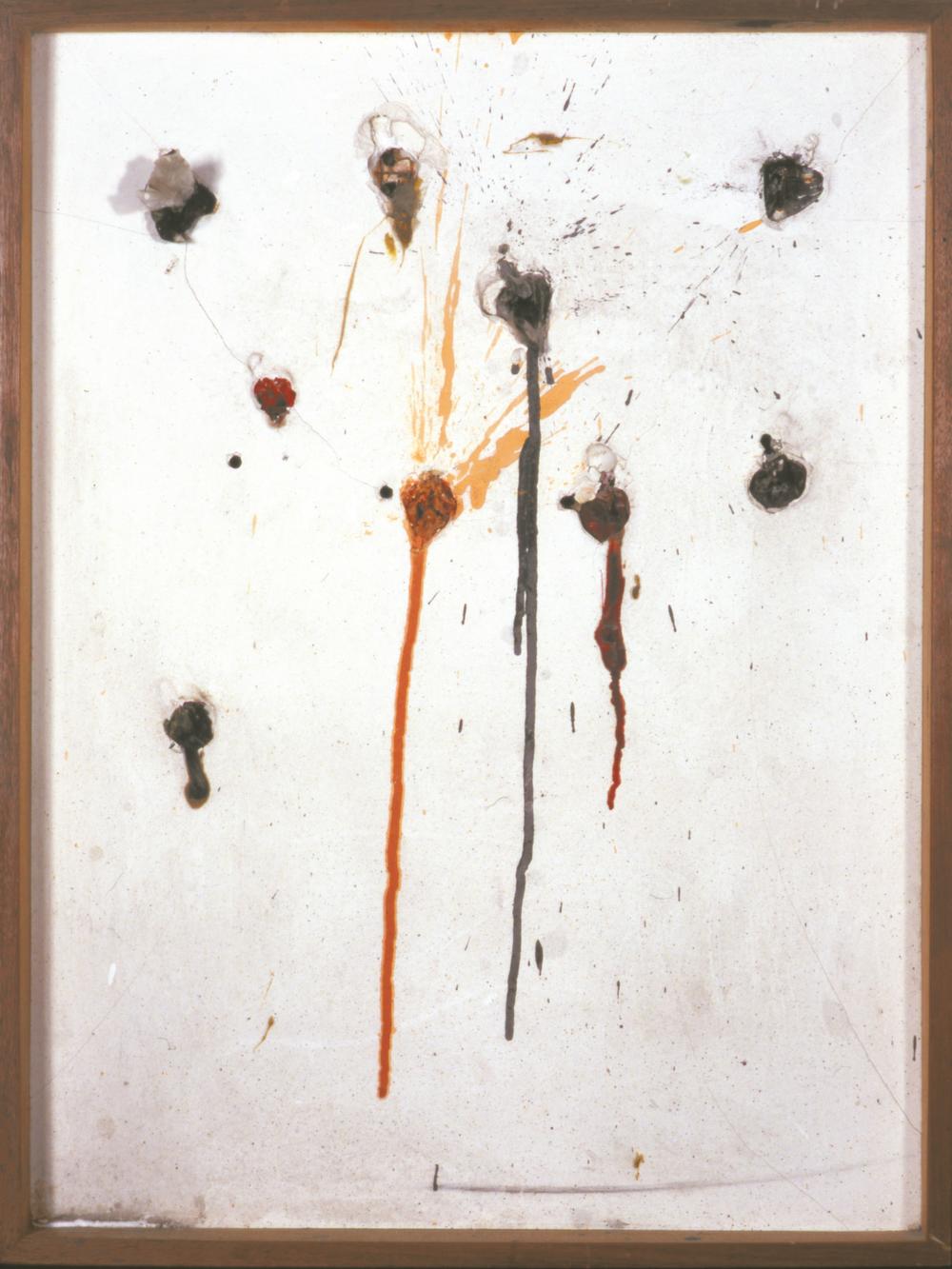

Co-authorship was also crucial for the final series of shooting paintings. In 1964, the artist participated in the Edition MAT (=Multiplication d’Art Transformable brought out by Daniel Spoerri. The MAT was designed to offer works – above all pieces by Nouveaux Réalistes – as multiples – i.e., a series of identical art objects, usually produced as a signed, limited edition. De Saint Phalle created up to a hundred framed “Tirs”. As such, though the artist creates the work, she places their “realization” entirely in the hands of the audience. Consequently, this further reinforces the open-ended nature inscribed in all “shooting paintings”. In fact, the handling of these paintings – if it was documented at all – was very different. Apparently, some buyers didn’t dare shoot and left the paintings in their original white state. Others reported that it was a challenge to fire an effective shot at the painting.

Niki de Saint Phalle, Tir neuf trous - Edition MAT, 1964, © 2021 Niki Charitable Art Foundation, Image via gpb.org