Peter Doig draws inspiration from the Group of Seven and creates unique, almost eerie paintings. But what makes the art of the Canadian landscape painters so fascinating?

After a prolonged period of time spent in the city, if you head for the country – or even better the wilderness, such as a lake surrounded by steep banks and pine forests – then after a short time you notice the absence of sounds. Then, generally a little later, as if your ears first had to tune in, you start to hear things again: the birds, the wind, perhaps the waves across the lake. Nevertheless, a feeling of emptiness remains which can become a little eerie. This Twin-Peaks-like eeriness is captured by the painter Peter Doig, who likes to look for themes in the environment of the Group of Seven.

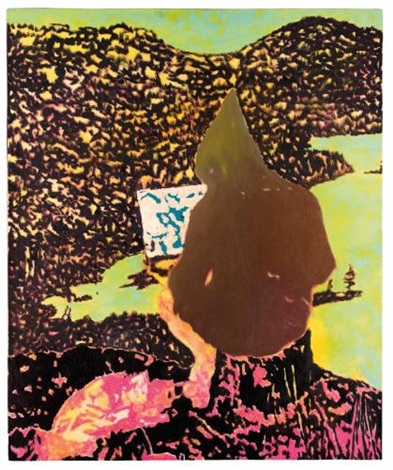

An example of this approach is a photograph by Joachim Gauthier, himself a painter who occasionally exhibited with the Group of Seven, from 1934. It shows a person squatting on a rock with his back straight, a dark, pointed hood over his head, beside him an open backpack. On his knees – we know that the figure in the picture is the Group of Seven painter Franklin Carmichael – he balances a small canvas, or perhaps a drawing board. In the background, the landscape opens up just as landscape vistas open out in paintings: a large lake, framed by mountains. The photo was taken on Manitoulin Island, an island on Lake Huron, and it looks as if it had already been painted. The artist can be seen as a figure viewed from the back; the hill delimits the pictorial space which opens up sublimely to the horizon. Gauthier’s photo follows the conventions of landscape painting. From the lower left, a pine branch juts out into the image. You can almost feel the breeze in which the tree gently sways, yet your gaze invariably lingers on the strangely dark figure that so dominates the photograph.

The figure remains enigmatic

If you didn’t know that this was Carmichael, he would be hard to identify. The figure remains enigmatic. Perhaps this is the reason why painter Peter Doig – born in Scotland in 1959, raised in Canada – finds it so interesting. So much so that at the end of the 1990s he tackled this photograph – or, more precisely, reproduced it – in a series of works. The most uncanny of these is the painting that Doig calls “Figure in a Mountain Landscape” (1997), as if here one painter wants to make the other painter anonymous. Doig paints the figure, mirrored, against a psychedelic explosion of color as if in a grossly overexposed photograph. In other versions the artist produced during the 1990s, the crouching Carmichael is depicted as a dark silhouette against a monochrome sky, the landscape reduced to a few rudimentary elements, namely the chain of mountains in the background, and a hard horizontal line, the lake.

Peter Doig, Figure in a Mountain Landscape, 1997,

Courtesy the artist, Image via www.artnet.com

When you’re exposed to the empty Canadian landscape, wrote Northrop Frye, it’s like being a child who has eaten too much cake. You have bad dreams, at some point something unknown and potentially terrible peers out at you from the darkness: the nightmare. Even if the land has been mapped and is crossed by trade routes, a residue of emptiness remains. The imagination has not yet absorbed it, wrote the critic in an essay in 1940. This nightmare passes from the explorers to the artists; from then on they have to come to terms with the emptiness and solve its riddles. This is the task confronting the painters of the Group of Seven, wrote Frye. Certainly, the void is one of the most enduring narratives employed to justify colonial expansion, yet North America was not empty, and perhaps that’s precisely where the eeriness lies. In the paintings by the Group of Seven, people are absent, yet paradoxically their presence is felt. In this instance, the myth of emptiness is a welcome tool for suppressing violence against the Indigenous population.

In the paintings of the Group of Seven people are absent

Emptiness and eeriness, according to Frye, are hidden in the paintings by Tom Thomson in their twisted branches and scattered boulders, among the bright colors. Thomson was the member of the Group of Seven who drowned in mysterious circumstances in 1917 during a canoe trip. Thus, he provided the tragic myth at the beginning of the group of artists that is so powerful that even now, in the district of Muskoka, Ontario, you can book Tom Thomson Getaways complete with a final canoe trip.

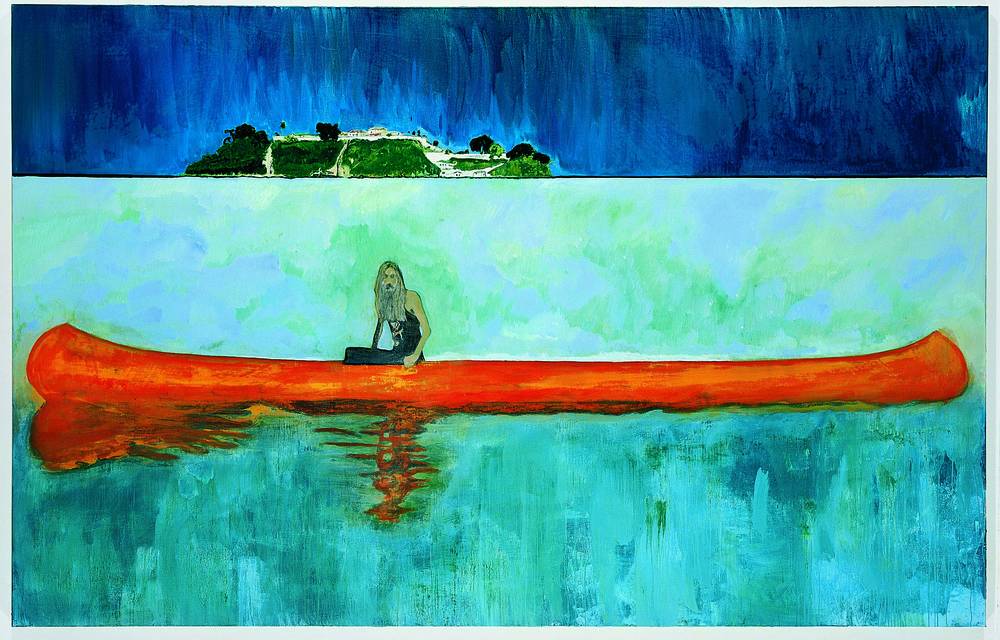

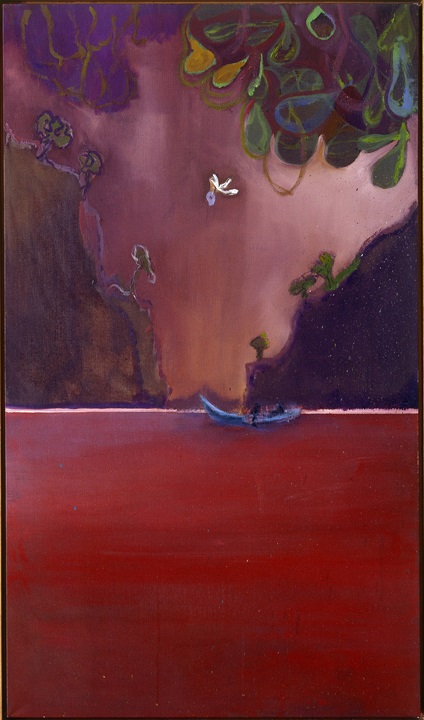

All the more eerie, therefore, is the theme Thomson repeatedly took as his subject matter: canoes, always empty canoes on the shore, depicted in the pastose paint typical of his works, with a chromatic variety that – particularly in his later works – appears almost shrill. Here, Peter Doig and the Group of Seven fit well together, since Doig, too, repeatedly represents boats on empty, motionless lakes. One example is the painting “White Canoe” from 1990-1, in which the landscape is so abstract that the trees consist of vertical white and rust-red lines against a very dark background and are reflected in the mirror-smooth surface of the water.

The colors are as intense as those of Thomson, yet Doig’s painting also gains its intensity from the nervous chiaroscuro that conjures up a hot summer day in a dark coniferous forest. Only the boat of the title is so white that one almost wants to squint when looking at it (Thomson’s own canoe, incidentally, was grey-blue, not white). And if you look very closely, then you see that there is something in the reflection which shouldn’t be there: a figure – perhaps – that is only there in the reflection, not in the boat, like a ghost.

Peter Doig, White Canoe, 1990/1, Courtesy the artist, Image via www.artlyst.com

In his last book before his suicide in 2017, “The Weird and the Eerie”, culture critic Mark Fisher developed a theory that sums up precisely this feeling of emptiness, this strange simultaneity of the present and the absent. The eerie, Fisher writes, represents a detachment from the familiar; it is actually quite a comfortable calm; it lacks any moment of shock. In this, it is very reminiscent of the Group of Seven’s desire to distance themselves from the banality of urban modernity.

The “weird”, meanwhile, is the presence of something that should not be there, as in Doig’s later paintings. In his canoes sit bearded, long-haired figures who stare blankly out from the picture. They draw from the iconography of pop culture; hence, for example, in this figure one can see the demonic Bob from David Lynch’s series “Twin Peaks” – which, not coincidentally, also plays out in the wooded mountain country of the north Pacific coast, very close to Canada, while other images take the horror film “Friday the 13th” as their model.

Doig’s images therefore do not lend themselves so easily to a colonial narrative, since he uses the Canadian landscape only indirectly as a transcendent place of longing. Since 2002 Doig has no longer lived in Canada, but rather in Trinidad, where he also spent a few years of his childhood. “I was nervous about coming here,” Doig told The New Yorker magazine, “as a white guy from the UK coming back to a former British colony, but I’ve always felt connected to this place. I believe that most of my works made in Trinidad question my being there.” He still paints canoes, albeit one that now float in tropical waters.

MAGNETIC NORTH. Imagining Canada in Painting 1910–1940

Extended until 29 August 2021!