Just what constitutes a sculpture? Inspired by Gilbert & George, who first became “Living Sculpture” in 1969: 10 sculptures that are only recognizable as such at second glance.

1. A very warm Welcome: Gilbert & George, Magazine Sculpture, 2021

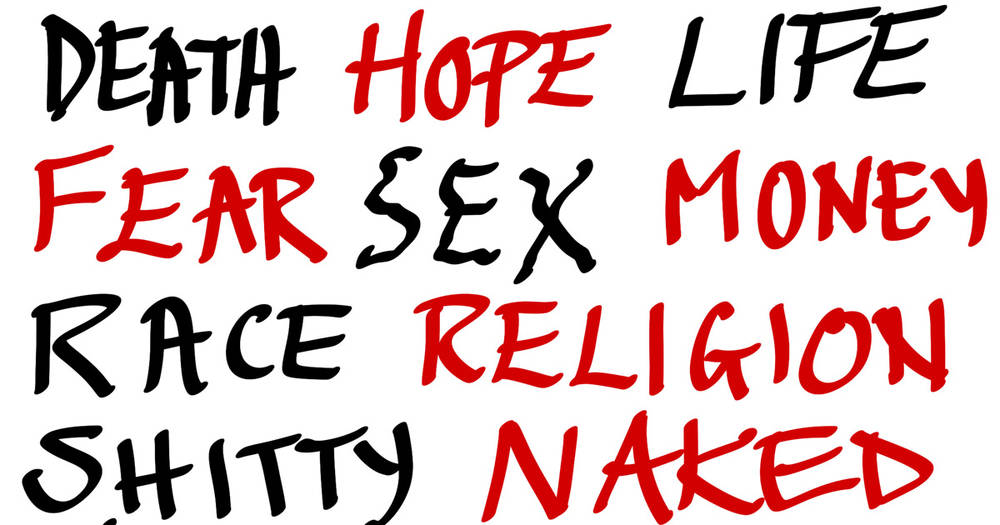

Since the very first time they met Gilbert & George have been questioning (artistic) conventions. While, in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the art world around them was largely preoccupied with Pop Art, Minimalism, and Concept Art, Gilbert & George developed their own idiosyncratic vision. For them, what was most interesting was not the objects themselves, but the way they themselves as a duo function as “living sculptures”. Although their art occurs in a large number of media, they perceive everything that they do as a sculpture. Post sculptures, charcoal-on-paper sculptures, drinking sculptures, video sculptures and magazine sculptures. For (virtual) visitors to the SCHIRN there is a special magazine sculpture for 2021 – to look at, read, print out, throw away, as a screensaver or postcard.

2. Enchanted Colossus: Giambologna, Colosso Dell'Appennino, 1570s

In the magical Villa Demidoff in Pratolino near Florence, even now, more than 500 years after it was produced, the gigantic “Colosso Dell’Appennino” by Giambologna continues to astonish visitors. Almost 11m in height, this colossus appears to rise up out of the waters of a small lake, its stone presence towering over the park laid out by Francesco I de Medici in the 1570s. At the time, countless sculptures and water features, known as meraviglie (miracles) adorned the grand duke’s love nest; today the Appenino is one of the few preserved and still extant artworks in the park. However, the colossus has a number of secrets and surprises hidden within it! Its corpus has a many hidden chambers, water features and grottoes which were once richly and intricately decorated. Its complex hydraulic system even meant that at one time water flowed out of the giant’s eyes.

Giambologna, Gigante dell'Appenino, firenzealchemica.eu

3. Palace of Memories: Es Devlin, Memory Palace, 2019

In her “Memory Palace” installation Es Devlin materializes key moments in history. Inspired by the ancient mnemonic technique which linked memories to familiar places, this British artist creates a space-consuming sculpture that is 18 meters wide. Providing a unique perspective on the last 75,000 years, it allows for a reinterpretation of time and space. Large-format mirrors reflect the sweeping diorama, creating an immersive environment. Within this three-dimensional historical map Devlin presents identifiable fragments of cities and buildings, producing a personal atlas of the evolution of thinking – for instance, the sacred fig tree under which Siddharta had his epiphany stands next to the Acropolis in Athens, the first known drawings in the history of man are immortalized, as are the steps of the Swedish Parliament on which Greta Thunberg started her “Skolstreijk för Klimatet”. This selection of events invites viewers to immerse themselves in the landscape and to think about the unpredictable nature of human history and about our place in it.

Es Devlin, Memory Palace, Image via pitzhanger.org

4. A Pyramid Made of Beer: Cyprien Gaillard, The Recovery of Discovery, 2011

Let’s linger for another moment in ancient Greece. While it was presumably wine that was served in that city, in Cyprien Gaillard’s “The Recovery of Discovery” we are talking about is beer. To put it more precisely, about the crates used by Turkish beer brand ‘Efes’ – the Turkish name for the ancient Greek city of Ephesus. In 2011, in the exhibition hall at Berlin’s Kunst-Werke, Gaillard constructed a staggered, accessible and usable pyramid made of assembled crates of beer containing 72,000 bottles of beer which visitors were then allowed to drink. As the visitors drank this beer the pyramid became increasingly unstable, something that was, of course, factored in – this can be interpreted as an allegory for the destruction of historical monuments by mass tourism. Suddenly, experienced connoisseurs of art are equated with the kind of loutish tourists with whom they would normally hope to have so little in common. Boozy jollity meets art for all!

Cyprien Gaillard, Recovery of discovery, 2011, KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, Image via www.artberlin.de

5. Space in space: Monica Bonvicini, Passing, 2017

For years now, Monica Bonvicini has been investigating the complex relationships between space and content. In 2017, in the form of her extensive intervention “Passing,” standalone scaffolding blocked the entrance to the exhibition gallery behind it at Berlinische Galerie. With its open structure, the scaffolding wall resembled a set, thus acting as an anonymous sculptural element. Visitors were able to pass through a door to gain access to the other side, presented as a wall made up of aluminum panels. The silvery, slightly reflective metal interacted with the artist’s other works and simultaneously led to a reflection on space itself.

Monica Bonvicini, Passing, 2017 (c) Monica Bonvicini und VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2017, Image via monicabonvicini.net

6. The Box Man from London: Gustav Metzger’s Auto-Destructive Art

In 1959, Gustav Metzger, also known as the ‘Box Man’, published his first manifesto. This advocated the kind of works that “contain an element that automatically leads to their own destruction within a maximum of 20 years” so that they can simply be removed from the location of their genesis and in this way eliminated. Throughout his life, Metzger remained on the fringes of the art world, his “first public demonstrations of auto-destructive art” on London’s South Bank are nonetheless legendary. It was here, for example, that he covered a pane of glass with a nylon fabric which he had previously, away from the eyes of his audience, submerged in hydrochloric acid solution. The nylon had accordingly started to gradually dissolve during the course of the performance. One of these “demonstrations” was observed by Pete Townshend, the guitarist of The Who, who subsequently started smashing up his guitars on stage, inspired by Metzger.

Gustav Metzger, First Public Demonstrations of Auto-Destructive Art, Presented by the artist 2006 © Gustav Metzger, image via tate.org

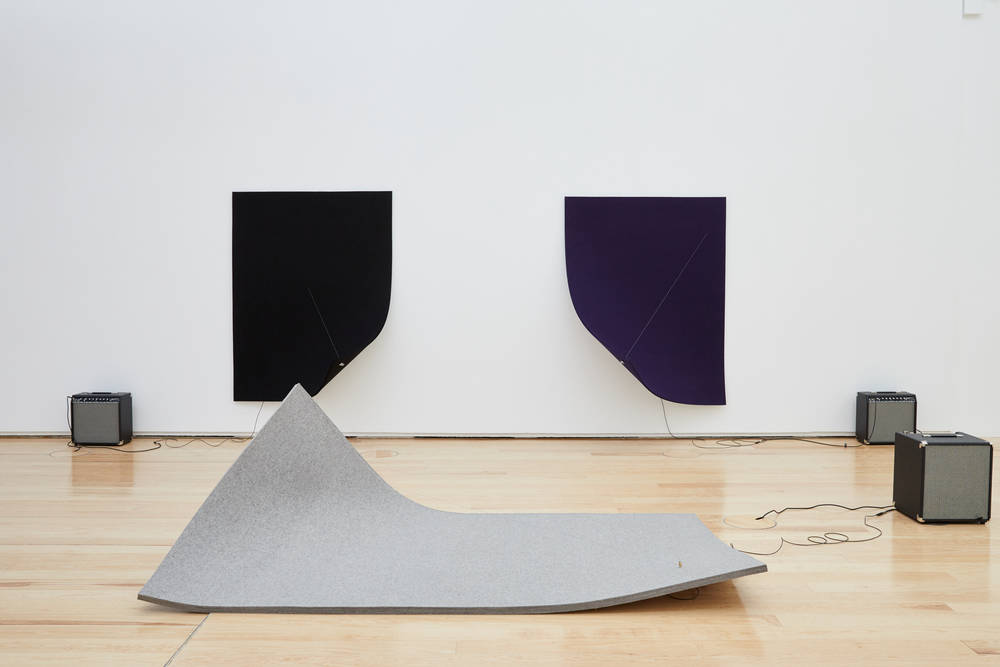

7. Between art and music: Naama Tsabar, Work on felt, 2019

Naama Tsabar is active in the areas of sculpture and performance, creating objects that function as both works of art and as musical instruments. She transforms not only broken guitars but also industrial felt into modifiable stringed instruments. The addition of piano strings and guitar tuning pegs lend these minimalistic sculptures the kind of new qualities that clash with their natural characters. The appearance of these transformative sculptures, the fact that their felt slopes or is straight, corresponds directly to the pitches that they generate. The works demand a great deal of physical effort, a willingness to commit to them, something that lends Tsabar’s performances an intense feeling of emotional tension.

8. Highly explosive: Cornelia Parker, Cold Dark Matter. An Exploded View, 1991

Cornelia Parker is well known for her processual, monumental installations. For her work. “Cold Dark Matter. An Exploded View” she blew up a garden shed in 1991. She then carefully collected up the broken pieces, bent and blackened by the force of the blast, and assembled them to make a sculpture – the moment of the explosion itself, the point when everything was rent asunder. Parker sees the explosion as the kind of archetypical image that is familiar to us from our childhoods. However, when the pieces are later reassembled, seemingly arbitrarily, a kind of metamorphosis occurs. The fragments of wood are reanimated and can be seen in a different spatial context. Contemplation replaces terror and memories of war and catastrophes.

Cornelia Parker, Cold Dark Matter: An Exploded View, 1991 © Cornelia Parker, image via tate.org

9. Art in the Middle of Nowhere. Elmgreen & Dragset, Prada Marfa, 2005

The installation “Prada Marfa” by art duo Elmgreen & Dragset has already been photographed millions of times and has long become an icon. This freestanding white building in the middle of the Texas desert is ostensibly a display window for the Italian luxury brand Prada. However, although the fashion company provided shoes and purses, the sealed display window located around 26 miles northwest of the city of Marfa is not exactly conducive to shopping. Instead, the piece relates to the artistic discourse on the white cube and the ready-made, in this case, outsourced to the empty expanses of the desert. However, this sculptural intervention can also be viewed as a criticism of consumerism – or as an intentional or unintentional way of strengthening the capitalist values criticized by it. And although initially only a few surprised cowboys were to be observed at the Prada store, only a short period of time later there were hundreds of calling cards propped up against the building’s windowsill, a way of visitors indicating that “I was here”.

ELMGREEN & DRAGSET: PRADA MARFA, Permanent Public Sculpture, Highway 90, Valentine, TX, Image via baustil.com

10. Confrontation in everyday life: Gregor Schneider. Haus u r / Totes Haus u r, 1985–ongoing

Gregor Schneider collects rooms. He has been doing so for 30 years now. He puts them together, erects them, destroys them and removes them from their contexts. Almost always, these are very ordinary rooms that act as catalysts, existentially confronting viewers with themselves. His principal work was “Haus u r” (house u r) on Unterheydener Strasse in the Rheydt district of Mönchengladbach – the “u r” stands for Unterheydener Strasse and Rheydt. A surrogate, “Totes Haus u r”, was awarded the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale. Schneider’s rooms are reconstructions of existing rooms in which viewers do not really have the opportunity to see the work in its totality. Walls are erected in front of walls, windows open up onto new windows, doors lead to bare walls or abysses. At times, rooms turn around, the roofs of rooms drop, electric fans cause curtains to flutter. Sounds like one of M.C. Escher’s impossible objects. Schneider’s rooms do not imagine anything that might have happened, instead they disturb and confront by tangibly erasing traces of use and life. What Schneider stages is something between eradication and preservation, something that even confounds our own grounding in time and space.

Gregor Schneider Haus u r, Rheydt, from April 2015 Feature, image via artreview.com