How the technological, medial and economic conditions of the music industry have changed is particularly evident in music videos. But what if the videos themselves are works of art?

There are two songs by James Murphy’s project LCD Soundsystem with the title “Someone Great”. One appeared in 2007 on the album Sound of Silver, is around six and a half minutes long and is about how Murphy learned of the death of his therapist and his experience of grieving. The other is just under four minutes long and is the single edit of the track that was shortened for airplay on the radio or on music TV.

The accompanying video by Doug Aitken plays with a double meaning: The therapist becomes a blackened silhouette of a woman walking through New York in the summer heat. She goes into a record store, meets people at a rooftop party, and first embraces someone before she appears to leave the party and the camera zooms in on the blackness of her outline. Fin.

The video begins, however, in bed: The silhouette has sex with a man who, while she dresses and leaves the apartment, appears somewhat downcast: “Someone great” is leaving him, it seems. So it’s actually pretty easy to interpret the video and thus also the song as the story of a breakup. The combination of music and lyrics, on the one hand, and Aitken’s video on the other creates an ambivalence. The theme of abandonment can be interpreted in two different ways, however – ultimately it’s equally possible to see a deceased figure in the black silhouette, who makes one final appearance in the memories of her lover, her record dealer, and her friends. Thus, from the original work the artist Aitken has created a new one by imbuing it with additional meaning.

“Someone Great” was released in October 2007 as an enhanced CD single which also included the video. Hence, at the same time, it is part of a bundle of goods intended to promote another product, the album “Sound of Silver”. Aitken’s aesthetic engagement with the song and its theme is likewise also an expression of the media and economic conditions of his time: It is still subordinate to the logic of the television age and the sale of music in the form of a sound recording or a download. Back in 2007, YouTube was barely two and a half years old and was not nearly as popular as it is today. Aitken’s video was only uploaded on March 12, 2009. One year previously, the platform had introduced a monetization system, whereby musicians and labels uploading music videos themselves could make at least a modest profit from the format.

How YouTube replaced the television age

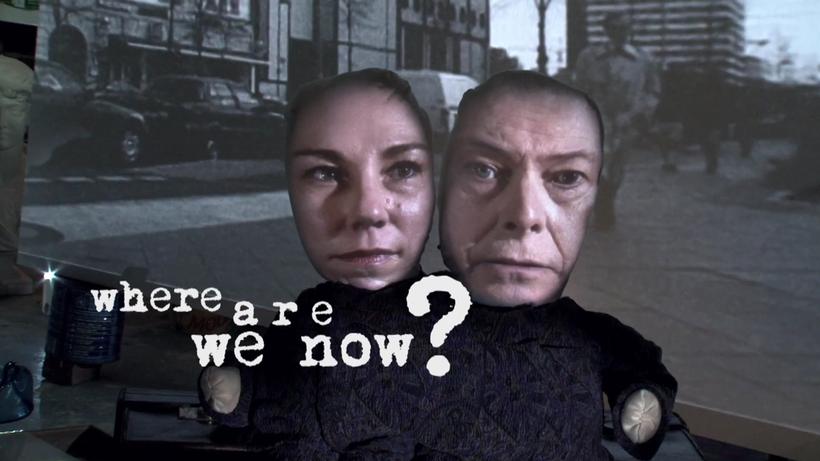

“Where Are We Now?”, a video work by the artist Tony Oursler for David Bowie’s song of the same name, shows the way the technological, media and economic conditions changed in just a few years and impacted on artistic engagement with the music and lyrics of a song. Unlike “Someone Great”, it was uploaded directly onto YouTube on the day of release – January 8, 2013, Bowie’s 66th birthday – and embedded on his website. The release, Bowie’s first in ten years, was not preceded by any kind of press release or promotional campaign. In other words, the surprise release was the PR campaign in itself. Oursler’s video is minimalist in its design and works with footage taken with a handheld camera in a dimly lit art studio, as well as archive material from West Berlin in the 1970s, which Bowie sings about in the song.

As with “Someone Great”, it expresses a melancholy, the feeling of having lost something irretrievably. Unlike Aitken, Oursler makes the singer the protagonist: Bowie’s face is projected onto the head of one of two stuffed toys, the other of which shows the face of Oursler’s wife Jacqueline Humphries. While Humphries seems to be listening intently, Bowie’s hovering face sings the song. In the background, the archive footage appears on a projection screen, while the lyrics fade in and out in the foreground.

The representation of the two figures as a “face in a hole”, as Oursler dubs it, is a reference to the stands in amusement parks and tourist attractions that serve for playful photographic documentation – basically preservation of memories. Hence, the video work by the artist places itself even more clearly in the service of the actual song by visualizing its theme and making it comprehensible through the incorporation of the lyrics to accompany the song.

A scene from the music video "Where are we now?", 2013 © Screenshot Youtube, Image via www.zeit.de

“Where Are We Now?” therefore differs from “Someone Great” in its treatment of the fetish figure of the pop star and their personal emotional life, but also of the logic of a new economy of the YouTube age that had already dawned at that point. Just as the incorporation of lyrics was an added incentive for fans to watch the video repeatedly and thus promised additional income through YouTube, small, skillfully embedded details also pointed to the private mythology of David Bowie as a public figure and his time in West Berlin.

A broad frame of reference opens up, which prompted fans and the press to eagerly discuss these references following the release. The video thus promoted the song as well as itself. The extent to which this was Oursler’s intention is another matter, but in the years that followed the principle caught on ever more. It came to a head with Hiro Murai’s music video for Childish Gambino’s song “This Is America” from 2018: The high density of historical and cultural references prompted broad discussion about it, and the scavenger hunt for the discovery of this or that reference meant that the video was played ever more frequently.

In the media transformation, the music video has thus defined itself ever more as a digital commodity that can be continually re-energized, whose aesthetic design contributes significantly to its (replay) value. The question arises here of the extent to which an artistic intention such as Aitken’s reinterpretation of the source material can escape this logic at all.

The music video defines itself as a digital commodity

It is a problem that likewise characterizes Arthur Jafa’s work on Kanye West’s song “Wash Us in the Blood”. The video, released on June 30, 2020, collages shaky smartphone videos of aggressive police behavior during Black Lives Matter demonstrations with a 3D rendering of West’s face and shots of Black people in different situations: dancing and singing, fighting, rioting, playing video games, in the hospital. The thoroughly topical visual references to racially motivated police violence are largely oriented to the text – “Genocide, what it does / Slavery, what it does” – and open up dual aspects on a pictorial-thematic level in the fetishization of Black culture and the actual violence against Black people in the USA.

Jafa’s video, which in parts uses a split-screen format to juxtapose and contrast various images, is marked by a similar ambiguity to Aitken’s interpretation of “Someone Great” and yet is as rich in references and shaped by the rapper’s iconic status as Oursler’s “Where Are We Now?”. It is a postmodern work of art, both an expression of and a comment on the media overstimulation of its time.

In this way, however, it unexpectedly aligns with the same logic that was defined by “Where Are We Now?” or videos like “This is America”. After all, it could not detach its aesthetic design from the economic constraints of the YouTube age: Due to its partially graphic content, the platform imposed an age limitation on it. In the comments, users cast doubt on the number of views displayed for the video – just over 11.3 million in the first year after its publication.

“[S]o we have proof the video was at 14 million, then it got age restricted, the views magically jumped to 10 million, and now theyve stayed at this exact amount since six months ago. the industry has a personal vendetta against this man and its disgusting”, wrote one user in March 2021. The reception of video art is completely overridden by its quantifiable, mercantile character.

As music videos became ubiquitous at the end of the 1980s with the success of music television, they were still primarily an art form that promoted a product other than itself: the music it visualized, commented on, and/or interpreted. Yet with the advent of VHS releases and ultimately the enhanced CD, it became a commodity in itself, which promoted itself within the digital environment. It is a process that is inevitably reflected in the aesthetic design of directors otherwise operating outside of the music industry, such as Oursler and Jafa, or which massively influences the reception of their works: Their aesthetics become inextricably subordinated to exploitability.

so we have proof the video was at 14 million, then it got age restricted, the views magically jumped to 10 million, and now theyve stayed at this exact amount since 6 months ago. the industry has a personal vendetta against this man and its disgusting.

Clubwalk

DISTANT BODIES DANCING EYES

9 to 11 July 2021, GIBSON, HAFEN 2, LOLA MONTEZ, NACHTLEBEN, ROBERT JOHNSON, SILBERGOLD, TANZHAUS WEST und YACHTKLUB