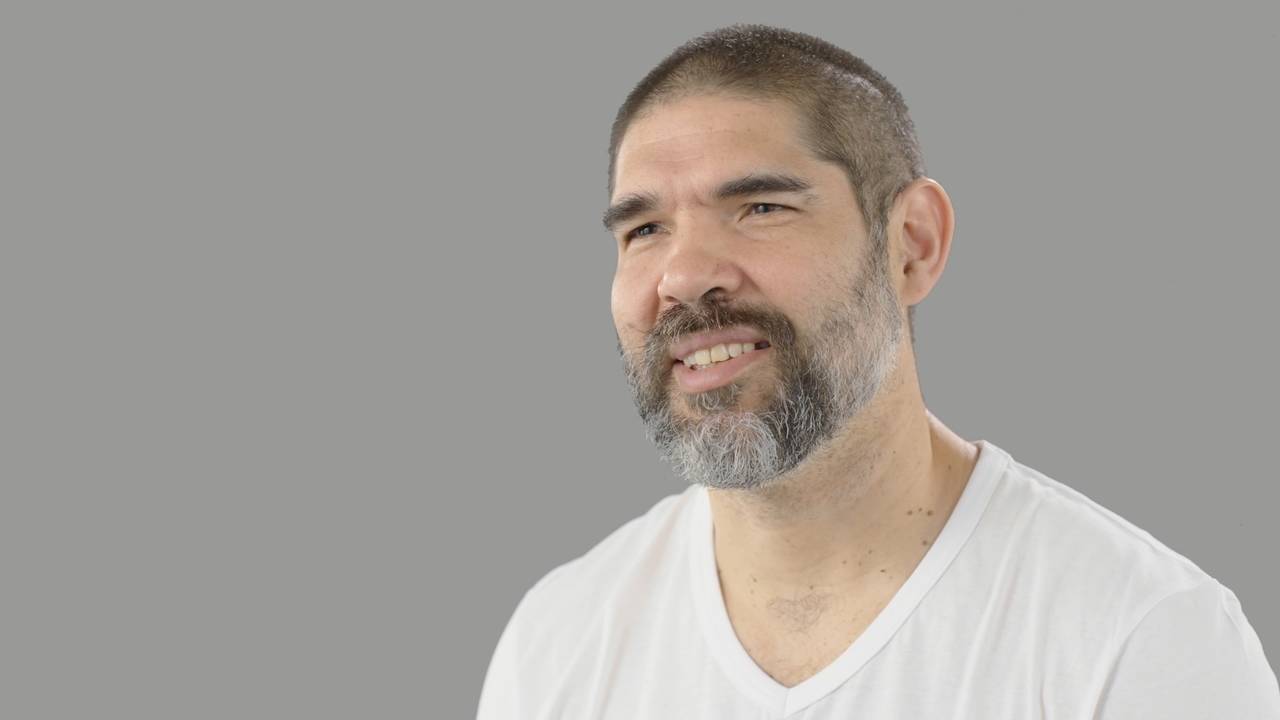

Together with deaf students, artist Tarek Atoui created new instruments – in search of a universal perception of sound.

There are instruments that are so rare that even regular concert-goers would need a bit of luck to hear them. The Ondes Martenot is one of them: Since 1928 this marvelous device has been a talking point as one of the first electronic musical instruments in the world – although to a layperson it initially just looks like a kind of organ. The instrument uses a wire, however, to produce swirling, unpredictable, ghostly sounds similar to those, incidentally, of the Theremin – a much more widely known instrument invented in Russia that same year (which many will know, for example, from the Beach Boys’ song “Good Vibrations”).

To this day, the Ondes Martenot remains a popular yet rare exotic item among musical instruments. French composer Olivier Messiaen wrote an entire piece for the instrument, “Radiohead” guitarist Johnny Greenwood loves the instrument deafly, and even Daft Punk like using the extraordinary sounds of the Ondes Martenot for their recordings.

Instruments galore from all over the world formed part of the museum collections

That said, among the more exotic instruments the Ondes Martenot is at least relatively well known. So, what must all the musical equipment have been like that artist Tarek Atoui was able to discover a few years ago at Berlin’s Dahlem Museums? Instruments galore from all over the world formed part of the museum collections, not one of which the sound artist was familiar with. And not one of which came with instructions on how to play – a few brief notes had to suffice by way of indications. Atoui invited several musicians to his rehearsal and recorded the sessions. In a second stage, he then played these recordings to instrument-makers and asked them to build devices that would make the same kind of music – a principle that’s familiar from reverse engineering, i.e. the construction of equipment and machines based on existing models.

Ondes Martenot, Image via wikimedia.org

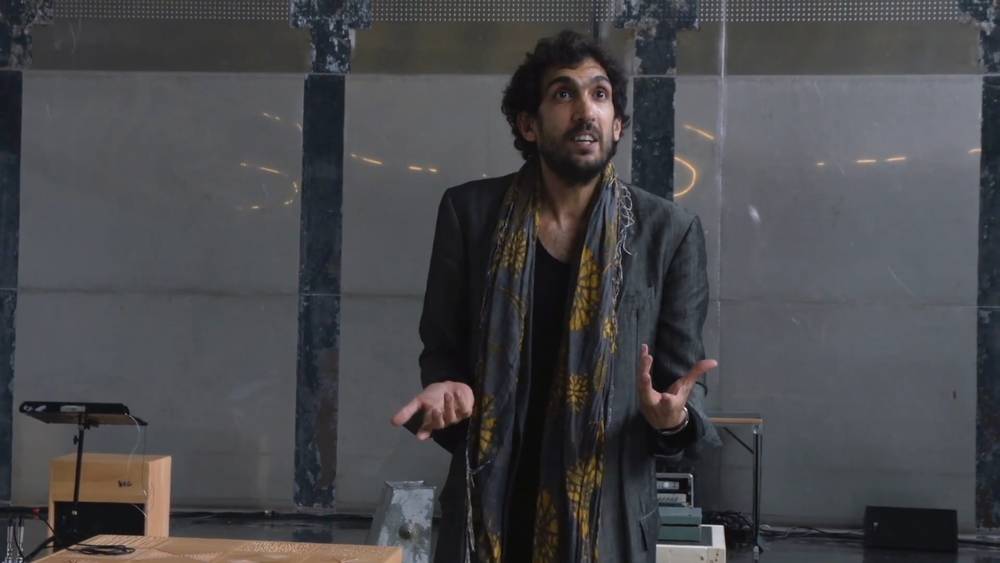

Subsequently Atoui brought each of these newly built instruments to the stage himself under the title “The Reverse Collection” – like the “Koto”, a construction made of bunched organ pipes that are connected to an air compressor via copper cables and whose sounds could be heard, for example, in the “Reverse Collection Sessions” at London’s Tate Modern.

Tautly stretched drum skins with colorful marbles and well-worn bouncy balls

A similar form of experimental instrument research is involved in the seemingly puzzling gadgets that are currently being presentedon view at the SCHIRN: tautly stretched drum skins on which, for example, brightly colored marbles and well-worn bouncy balls await an as yeta yet indeterminate purpose. They are initially merely something to look at, to be brought to life when played. Some of these instruments stem from Tarek Atoui’s collaboration with the Al Amal School for Deaf Students, where the artist first met up with deaf and hearing-impaired students in 2012 to explore the possibilities of sound creation.

As is usual for Atoui, he again worked with experts in the field, with composers or instrument-makers – or, in this case, with the designer Thierry Madiot. In playing on the resulting instruments and in the performances inevitably questions arise that no doubt interest artists and audience alike. Is there a universal reception of music and sound that goes beyond individual perception? And if so, where might we find it? In the deep bass frequencies, for example, that observers can feel at least as strongly as they can hear them?

Alongside these sorts of tactile experiences, Tarek Atoui’s works also offer very simple visual qualities, for example, which can then be perceived by both deaf and hearing people alike: Similarly to the legendary Ondes Martenot, the works of the series “Iteration(s) on Drums”, with their colorfully shimmering tops appearing like the product of a child’s playroom, also develop the allure of fantastical, carefully considered instruments – all the more so once you know they can indeed be played.

Since 2012 the artist has therefore been on a permanent mission, sometimes to expand sound perception by the most individual sensations, and at others to pinpoint it to one denominator common perhaps to all people, be they deaf or hearing. Born in 1980 in the Lebanese capital Beirut, at 18 years old Tarek Atoui moved to France to study contemporary and electronic music at the conservatory in Reims. Ten years later he became co-director of the STEIM Studio, an Amsterdam institution for electro-instrumental music. In between times, Atoui records his own tracks and designs software tools that can be used both as raw materials for his own compositions and as a tool for musical training. He is probably best described as a musician, Tarek Atoui once surmised in an interview with “Ibraaz” magazine, but he doesn’t seem to be truly happy with this self-characterization.

Likewise, Atoui does not feel himself to be part of a community of musicians. This may because of his equitable notion of authorship – or rather his rejection of any classic understanding of works or authors as such. In other words, he is very much in the spirit of the times, of course, in which even animals can be given credit for paintings and photographs and the artist or curator collective represents an increasingly popular way of creating work. Yet where there is no single author, clear definition of the artwork can sometimes be difficult: The constructed instruments are initially just extraordinary instruments, while the sound recordings are mere documentation of their being played.

Sound permeates all matter as an elemental force of nature

The common thread running through Tarek Atoui’s work is most likely the fact that his interest lies less in classic music-making or writing of song structures and more in the sound itself, which permeates all the material as an elemental force of nature. Atoui likes to talk about the resonance that the sound triggers in its environment – and that too is meant in quite elemental terms: The vibration of the sound, he explained in a video for the Tate performance, penetrates water, wood and all materials. A very particular form of resonance, one might add, is that of the human body itself, where sounds and noises may trigger not only various physical, but also the entire spectrum of emotional reactions.