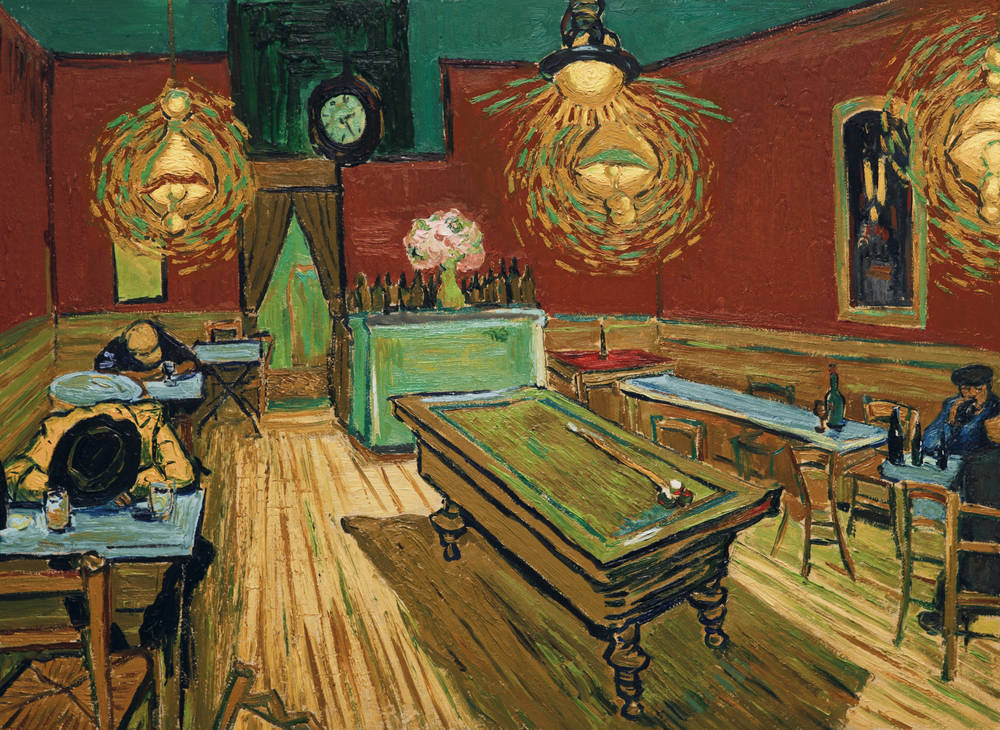

“Loving Vincent” is no art movie, nor does it aim to be: It is a film about the not fully clarified death of Vincent van Gogh, that draws on the artist own signature style.

“There’s something about the story that’s not right,” says the protagonist at one point, and in doing so he summarizes that unease which is actually sparked by all good theories relating to conspiracies and guarded secrets. With a now iconic artist like Vincent van Gogh, this is the case even 130 years on: The circumstances surrounding his death in 1890 have still not been fully clarified, and it is this that is explored by the young Armand Roulin in the film “Loving Vincent”.

Van Gogh died as a result of a shot to the stomach, which he is supposed to have fired himself – yet experts in gunshot injuries say the wound proves this impossible. What’s more, the painter, as a final letter written by his own pen suggests, is supposed to have been thoroughly content shortly before his possible suicide in the French town of Auvers-sur-Oise. But what does that really mean in the case of a chronic melancolic?

Animation with 1,001 brushstrokes

In a slightly broader sense too, however, there is something about this film that’s odd: In this biopic the narration and narrative form, the dramatic composition and the visuals do not appear in God-given unity – which they after all never really constitute. At least not in the first quarter of an hour, or perhaps even a bit longer, before the viewer becomes accustomed to the unusual animation of 1,001 brushstrokes. “Loving Vincent” – and this is of course the unique selling point of this biopic, which has already been awarded a number of prizes for the extraordinary way in which it was made – aims for nothing less than to put Van Gogh’s famous paintings into motion.

With around 800 themes, all painted by the Dutch artist in just eight creative years, the filmmakers had a potential treasure trove on which to draw. From them, Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman chose famous scenes and figures to serve as backdrops and protagonists, which were staged for the film by more than 100 painters all working by hand.

Whodunnit?

In this way, the audience is able to follow Armand Roulin, the postman’s son with a final letter to deliver, as he attempts to unravel Van Gogh’s murder in a classic whodunnit: Sometimes the summery French meadows and pathways form a two-dimensional background, while at other times the canvas meanders and swirls in the nervous flickering and shimmering of changing strokes of color. Together with Roulin, we become increasingly immersed in the contradictions surrounding Van Gogh’s final days in the company of his doctor and the doctor’s daughter, in the guesthouse with its landlord’s young daughter, and surrounded by the village idiot and cynical young people, and in flashbacks we learn about the family that shaped Vincent and his brother Theo.

Was he an eternally depressive loner or even a stealthy womanizer? Witty and spirited or awkward and far too nice? The changing perspectives towards the painter from different companions then paint a more complex picture than that which the name “Van Gogh” immediately conjures up in the mind.

Delightfully bumpy stop-motion

After the initial amazement prompted by the world-famous portraits and landscapes being suddenly brought to life, one of the following may happen: Either you start to barely notice the animation and thus become thoroughly absorbed in the stories captured in oil paint. Or you instead succumb to the flashes of what is, in its best moments, delightfully bumpy stop-motion, and thus find yourself concentrating less on the action. Perhaps even both may happen alternately, making “Loving Vincent” a sometimes exhausting watch, as it repeatedly tears its audience away from the story.

The effect of the oil-painted animation doesn’t always work, however: At times it seems as if you can actually discern the underlying motion picture, which was filmed with real actors and then basically painted over. Then it suddenly feels rather like a kind of video game, the animated aesthetic of which is placed over the original image like a filter.

Animated Van Goghs

Amid this jumble, entirely different questions and considerations then arise: The concept of animated Van Goghs certainly has a degree of charm. It’s not for nothing that the painter’s images are at least high on the hitlist of the most printed art motifs on scarfs, postcards, calendars, watches and shoulder bags. And if the artistic legacy has long been considered public property anyway, why shouldn’t it then be used to make a film?

The Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, which is cited as a sponsor in the closing credits, clearly had nothing against this. The question of “why” is then never actually addressed: Ultimately the concept of telling a story about an artist in the style of that artist, which develops as a world from him and unfolds around him, is at second glance not such a compelling idea as the understandable rapture surrounding such a cinematographic project might suggest. And in this case it is even posthumous.

65,000 individual painted frames

“Loving Vincent” is no art movie and nor does it aim to be: It is a film about an artist that draws on his own artistic signature style. The conditions of its development and the string of considerations that come with it are not reflected in the film itself – it is simply about an experience. For long stretches this functions, in fact extremely well; but is it really an entirely new form or animation simply because oil paints and brushes were used instead of a computer in this case? Can we really make such a claim when a number of the originally 65,000 individual painted frames were ultimately unusable – and the individual transitions were then merged on the computer?

The images and the film’s development are certainly impressive, and the story can be followed as a nicely calm yet captivating whodunnit. Whether the form is really as uniquely thrilling as has been claimed, and whether the film would be perceived in quite this way without the knowledge of its development are matters that can still be questioned. What’s clear – and “Loving Vincent” demonstrates this too – is that the story that can be built around the story is as important for its reception as the work itself.

Baby, you can drive my car

For many years now, the art world has had a (love) relationship with cars, be it as a way of representing speed or critical reflection on consumerism....

The film to the exhibition: Selma Selman. Flowers of Life

Only a few years ago, she boldly and confidently entered into the spotlight of the international art world. In this video interview, she talks about...

Selma Selman and the elastic fabric of the Self

SELMA SELMAN's artistic practice cannot be described as site- or situation-specific; rather, it seems to deal with the self and its constant...

Now at the SCHIRN: CASABLANCA ART SCHOOL. A POSTCOLONIAL AVANT-GARDE 1962–1987

The Moroccan “New Wave”: The SCHIRN presents the influential art scene around the CASABLANCA ART SCHOOL in a first major exhibition in Germany.

FIVE GOOD REASONS TO VIEW SELMA SELMAN IN THE SCHIRN

Poetic, confrontational, surprising: from June 20 to September 15, the SCHIRN presents two new works by the artist SELMA SELMAN in a large solo...

A Sicilian myth in a contemporary guise

What if women can resolve and heal dichotomies? In the coming DOUBLE FEATURE, Elisa Giardina Papa takes the Sicilian myth of the “donne di fora” and...

REVISITING DOUBLE FEATURE: FOCUS ON QUEER ART

Our DOUBLE FEATURE series presents a variety of artists who deal with queerness in their work. We have selected some of the best video interviews for...

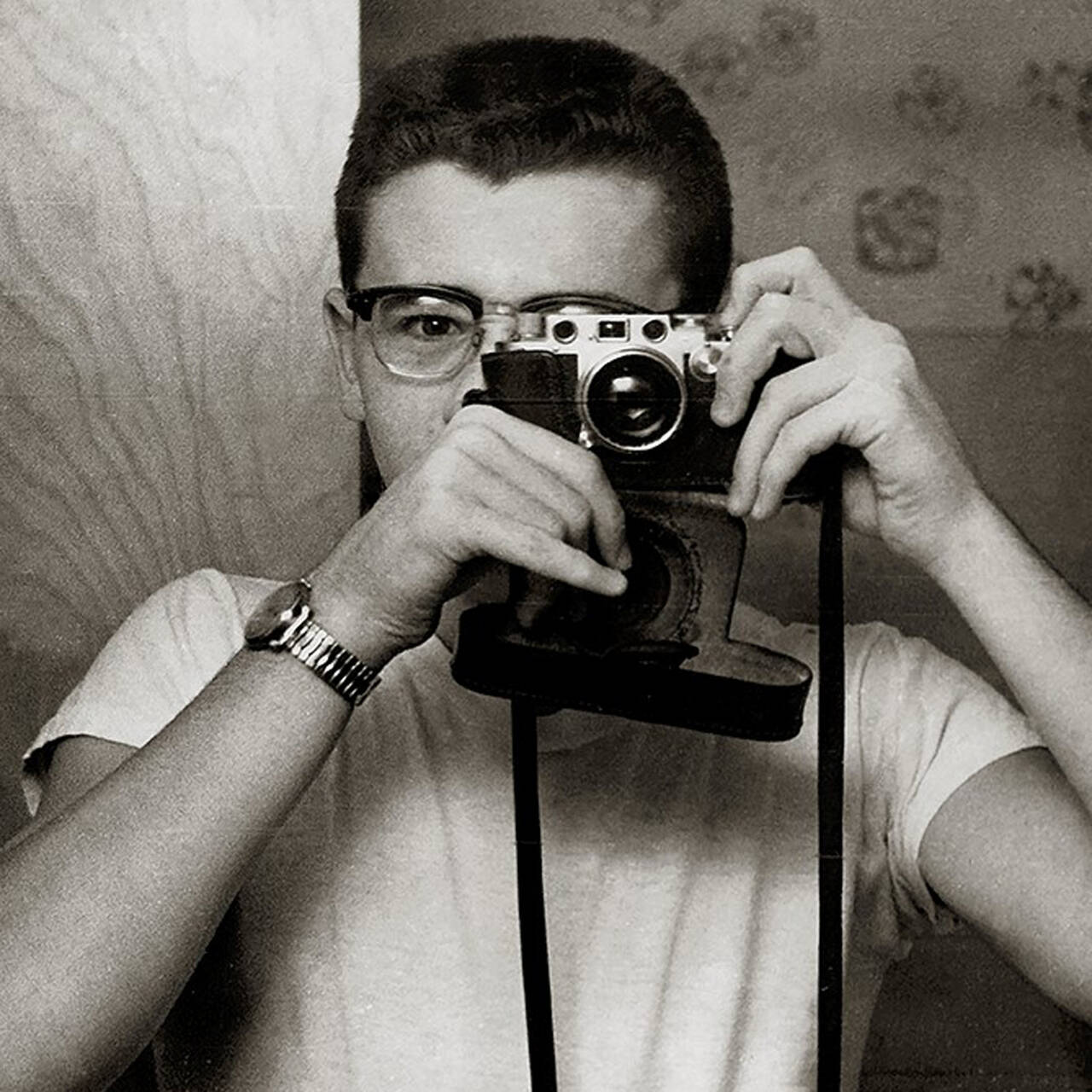

ABOUT TIME. With Abe Frajndlich

Abe Frajndlich can look back proudly on a career of over 50 years as a photographer. In conversation with us he speaks, among other things, about his...

A mix of meditation and leisure

What potential does leisure offer? What happens if nothing happens? In the form of “Untitled (Nothing Happens)” (2023), in the latest DOUBLE FEATURE...