Letter by Helene Schjerfbeck to the artist Maria Wiik, August 1916

In Finland, Schjerfbeck is venerated as a national heroine. On the occasion of her 150th birthday, in 2012 a two-euro commemorative coin was issued embossed with a self-portrait of the celebrated artist.

Helene Schjerfbeck’s career began in a time of a turbulence in her home country. The neighboring countries of Sweden and Russia had battled for centuries over rule in Finland. After the Russo-Swedish War of 1808–09, Finland became an autonomous grand duchy and part of the Russian Empire. It was not until much later that the Finnish national movement won Finland’s independence: on December 6, 1917, the Russian parliament declared Finland to be an independent democracy.

Women ordinarily did not have access to higher education until well into the 20th century. This also applied to art academies. Women were not thought capable of having the perseverance for a course of studies, nor where they believed to possess the required creative ingenuity. The only alternatives to an academy were private art schools, whose quality, however, fell way short of that of an academy. In addition, nude studies, an essential foundation of artistic training, were prohibited for women. Female artists could only acquire this knowledge second-hand, based on busts, or by copying works produced by other artists.

Finland introduced the vote for women in 1906, and in doing so assumed a leading role in Europe. Helene Schjerfbeck did not see herself as a feminist. Yet the nascent women’s movement also influenced her artistic career. In this progressive climate, one of the rights women won was to do nude studies.

In the late 19th century, Paris succeeded in superseding Rome as the capital of the arts. Those who wanted to advance their careers went to Paris. This is where the European art scene met; this is where new art currents were born. The ultimate goal of aspiring artists was to exhibit at the Paris Salon. This art exhibition, which was initiated in 1663, was initially open only to members of the academy. It was not until the late 17th century that the public was admitted. The Salon quickly developed into one of the most important artistic events of the year. Those who succeeded in convincing the harsh jury were almost sure to attract public interest and achieve financial success.

Among the various genres in painting, history paintings enjoyed the greatest status. Artists who were successful in this genre had a major career ahead of them. History paintings feature religious, mythic, or historical scenes. Pictorial themes are staged in a dramatic way and are intended to arouse grand emotions and convey high morals. The human figure plays a principal role in history painting. Anatomic knowledge and motion studies were therefore an important basis for artistic success.

Dust glistens in the air. Warm sunlight pours through the cracks in the black door into the shadowy room. Although there is apparently nothing happening in the painting, Helene Schjerfbeck, who was twenty-one at the time, succeeded in generating tension. The surface of the floor dissolves in chaotic brushstrokes and contrasts with what are otherwise clear surfaces with reduced coloration. In some places, the paint is applied vigorously, while in others the canvas shimmers through. By dissolving the spatial depth in color fields, the artist created a concentrated atmosphere using subtle means. Schjerfbeck demonstrates striking artistic independence in “The Door”.

Schjerfbeck’s painting “The Convalescent” was presented at the Paris Salon in 1888 and received a bronze medal at the World’s Fair in Paris in 1889. For an artist—and for a woman from Finland at that—this was an incredible achievement. However, in the late 19th century criticism of the Salon’s selection criteria began to grow. Those who were rejected started to create their own forums in counter-exhibitions. Schjerfbeck also began to free herself from traditional precepts in some of her works.

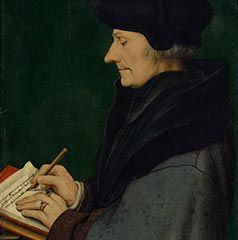

Hans Holbein the Younger, Portrait of Erasmus of Rotterdam writing, 1523

The portrait in the background features Erasmus of Rotterdam, a humanist and scholar from the 15th century. It repeats a painting by Hans Holbein the Younger that Schjerfbeck incorporates into her composition. She had previously studied the original at the Louvre in Paris.

Both women have a posture that is similar to that of the man in the portrait on the wall. Thus the motif is again taken up from two different perspectives.

In painterly terms, the women’s bodies are barely modeled. They appear to be as two-dimensional as the picture on the wall. Schjerfbeck could not have more clearly expressed the fact that for her, composition has priority—and not the persons themselves.

Both women are lost in thought in their reading. This lowered gaze occurs in many of Schjerfbeck’s portraits. The faces of her figures often have unnaturally light complexions and are mask-like. Thus the painterly aspect takes priority over realistic depiction.

In the center of the painting there is an orange dot. Its warmly radiating color forms a contrast to the cool tones of the background. The woman with pinned-up hair has folded her hands loosely on her lap. Although she is facing the viewer, her face remains anonymous. The extensive surfaces, the reduced formal language, and the clear contours are reminiscent of the Japanese art of woodcutting. Even her hairstyle and the kimono-like garment have something Asian about them. At the time, Japanese art was a source of inspiration for numerous artists. Schjerfbeck had been introduced to it by fellow artists in Pont-Aven who experimented with the stylistic means of the Japanese color woodcut.

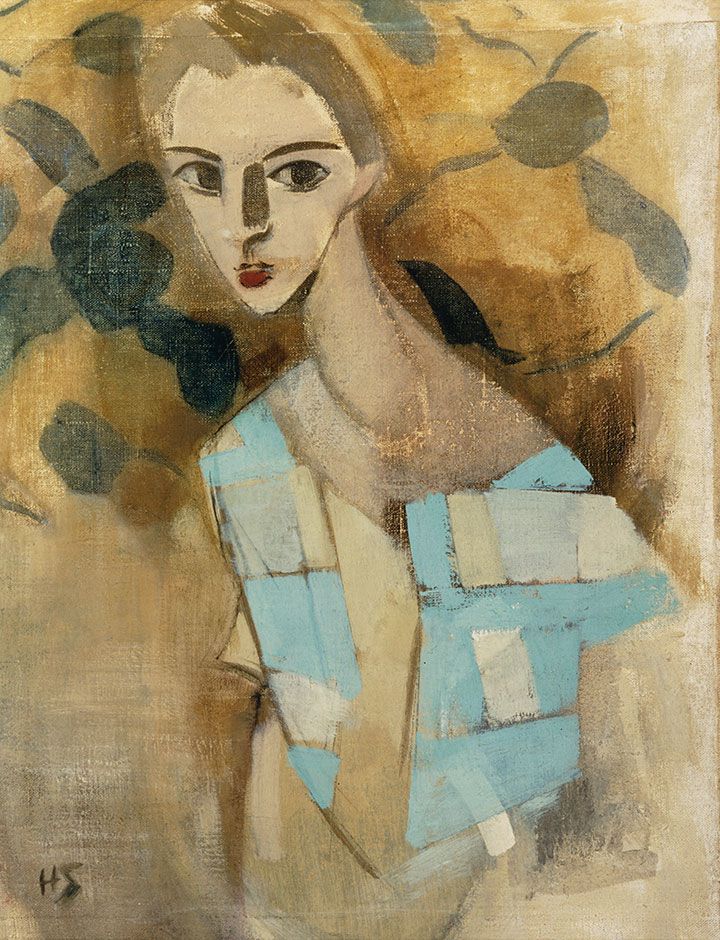

Red lips, slender limbs, a long neck, ever-shorter skirts, and a youthful silhouette: at the time, all of this corresponded with the image of a modern woman. Schjerfbeck was essentially a modern woman as well: she earned her own living, and she was one of the few female artists to operate outside of the prevailing social norms.

In Schjerfbeck’s portraits, the outlines of the women’s faces are often wraithlike. Their expressions alternate between dreamery, sadness, arrogance, and boredom, which was regarded as a phenomenon of modernity.

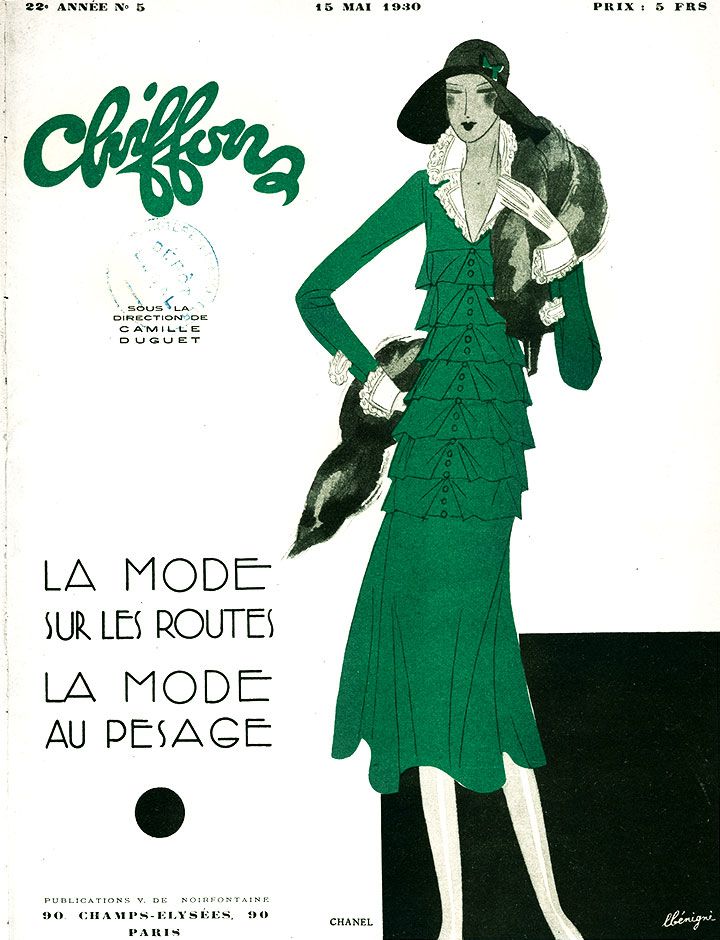

Schjerfbeck had a friend of hers send her fashion magazines; she made her clothes herself according to the latest patterns. Her involvement with French fashion magazines brought back ardent memories of her stay in Paris.

“Le Chiffon” was a French fashion magazine from the 1930s that Schjerfbeck regularly had sent to her in Finland. The French magazines that Schjerfbeck read did not contain haute couture but instead were modest, practical publications that primarily catered to middle-class women.

In 2012, Helene Schjerfbeck was the source of inspiration for the fall/winter collection of MES DAMES. The Swedish fashion label makes historical women the theme of its collections on a regular basis.

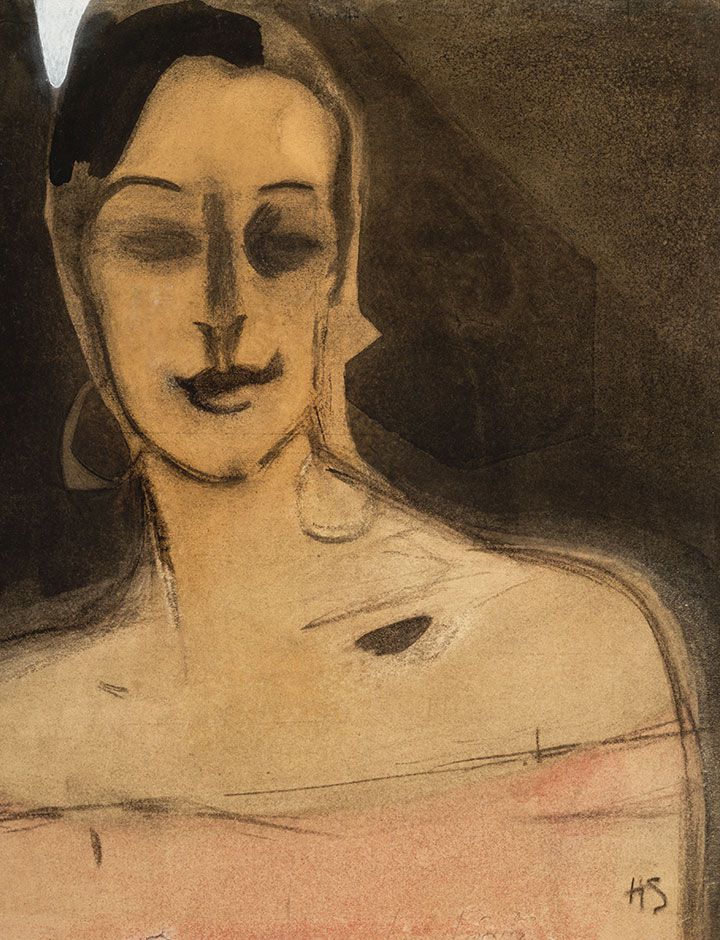

Schjerfbeck painted the striking face of her dear friend Einar Reuter with the use of crude brushstrokes and few lines. She heightens his high forehead, cheekbones, and ear with white. An ochre-colored stroke in the background highlights the slant of his elongated neck. She sketches his body with sweeping lines and almost abstract areas of color. To contrast the latter, she emphasizes his face by coloring his cheeks and neck red. This causes it to seem more vibrant than the body, which in painterly terms dissolves toward the lower edge of the painting.

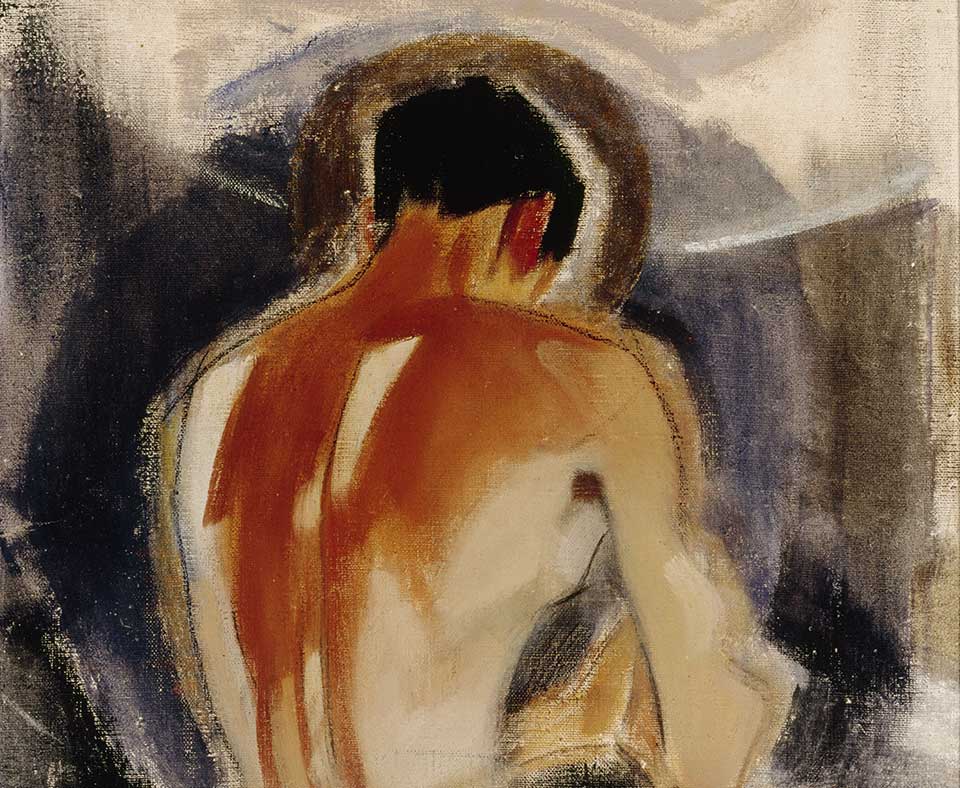

The sophisticated composition of the painting testifies to Schjerfbeck’s artistic finesse. By emphasizing the union of line, color, and form, she succeeds in communicating a great deal with a minimum of means. The man’s posture is roughly sketched. Two powerful, nearly abstract white strokes highlight his strong back muscles. The artist carefully frames the man’s body with keen, forceful lines. The pale line around his head and body contrast with the dark edging and lend the figure a radiant aura.

Stenman provided Schjerfbeck with visual material by other artists. And he asked her to reexamine the motifs of her earlier works. Stenman was convinced that these works would sell well: artists such as Pablo Picasso and Edvard Munch had also successfully taken up works by other artists and reinterpreted their own motifs. As inspiration, Stenman also gave the painter an exhibition catalogue with black-and-white illustrations of works by El Greco. In the late 16th century, El Greco, a Spanish painter of Greek origin, had developed an unusual style that inspired numerous modern artists. Helene Schjerfbeck was fascinated by his composition and the distribution of light in his paintings.

The dramatic story of the war hero Wilhelm von Schwerin is a subject that many Finnish artists took up. The writer Johan Ludvig Runeberg dealt with his heroic deeds in the poetry collection “The Tales of Ensign Stal”. The officer, just fifteen years old, was fatally wounded during the Russo-Swedish War in the Battle of Oravais in 1808 when he and his men started a counterattack against the approaching Russian enemy. The battle constituted the turning point of the war: the conflicts ultimately ended with Sweden’s defeat and the beginning of Russian rule in Finland.

Schjerfbeck produced the first version in 1879, when she was just seventeen years old. She painted the second one in 1887, shortly after beginning her studies in Paris. The final version was created nearly 40 years later. It was also to be the last history painting that the artist would produce.

An exceptional artist, an extraordinary oeuvre: In the SCHIRN you can now discover Helene Schjerfbeck. You will also find interesting details about the most important female artist of Finnish modernism in the richly illustrated catalogue accompanying the exhibition.