During her life-time US artist Channa Horwitz was hardly noticed in an art world dominated by men. Yet her tender and precise pieces were well ahead of their day.

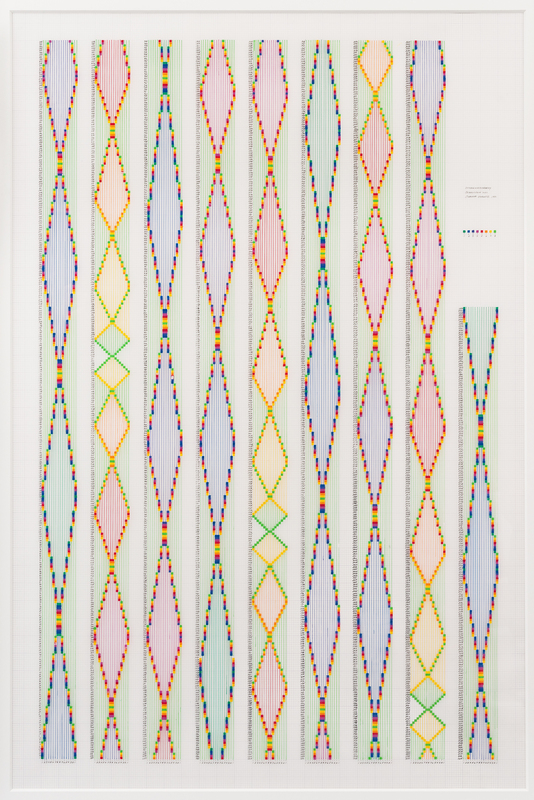

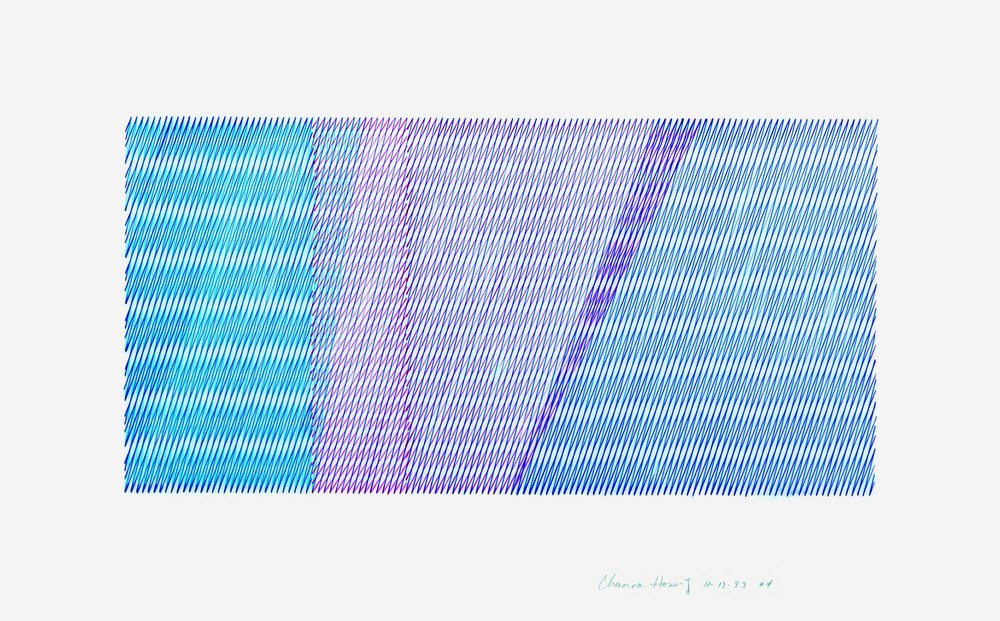

Small, colored squares dance as if on the vertical drawn lines of a musical score, giving rise to patterns and sequences of color. Tiny numerals are to be seen next to them. A key on the edge of the picture offers hints on how to decipher the composition. In her series entitled “Sonakinatography”, Channa Horwitz (1932-2013) made use of a notation system she had devised herself and which used graphs, figures and color to represent motion, sound and rhythm under spatio-temporal conditions. One inch stands for a heartbeat or “beat” for short – one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight. Each numeral is assigned to a specific color. Using this deductive logic, which she calls her “visual philosophy”, Horwitz created numerous works that are astonishing in their precision and possess a quite unique aesthetic appeal of their own.

Channa Horwitz, who studied at the California Institute of the Arts, among others under Allan Kaprow, submitted a project she entitled “Suspension of Vertical Beams Moving in Space” in 1968 to participate in the “Art & Technology” exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. She produced a sketch for a kinetic sculpture consisting of eight vertical Perspex elements that were attracted by magnets and each accompanied by four cones of light – moving between two horizontal platforms. The piece was as technical as it was poetic, but neither did it go on show nor was it ever realized, which is hardly surprising as both the technology world and the art scene in Los Angeles were absolute male domains. However, what it did do was prompt Horwitz to start developing her Sonakinatography series.

Structure as the basis for freedom

From then on Horwitz developed over 20 compositions that functioned not only as drawn systems but could just as well be understood and realized as musical scores, performances or installations. She also devised performances and dance pieces, but repeatedly invited others to interpret her notational scores. The stringent, close-meshed system actually allowed innumerable variations and possibilities. And this was what Horwitz had in mind: “I gain freedom from the restrictions and structure that I impose on my works. Because only on the surface are limitation and structure the opposite of freedom. I have come to a point where I grasp them as synonyms and the very basis for freedom.”

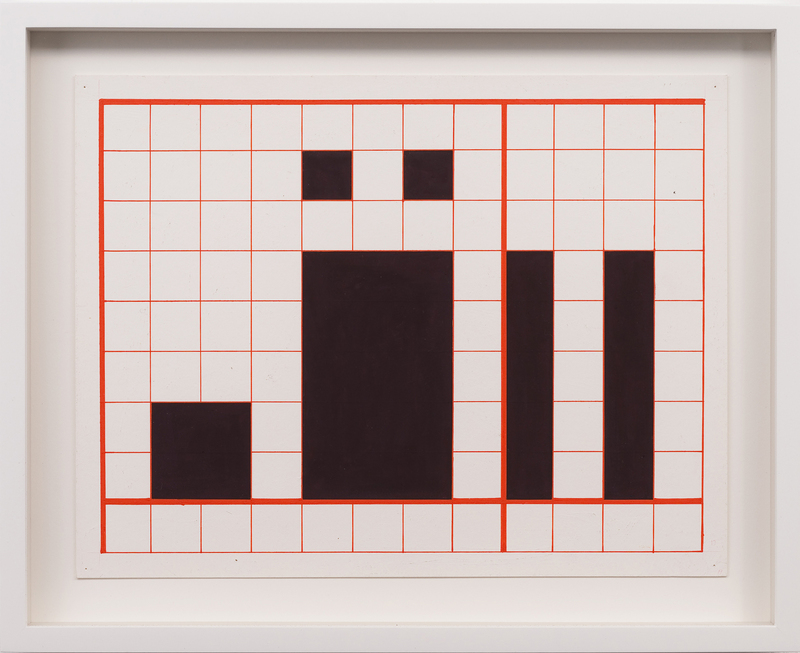

In her “Language Series” (which she started in 1964 but did not in fact realize until the Noughties) or “Circle and Square” (1966) Horwitz consciously limited her options: “I resolved to use circles and squares to represent all shapes, and black and white to represent all colors.” In her “Language Series” she either used American graph paper with its typical orange-colored grid or drew a grid herself, in which she then arranged squares and circles. She grouped the shapes, tried out shifts and overlaps, and played through countless constellations. Here, too, there was a numeral system based on the eight that set the parameters of the structure: eight times eight small boxes engender one a large one, and so one. When making her 16 “Circle and Square” pieces Channa Horwitz obeyed very clear instructions she gave herself:

1. Place two rectangles (one large and one small) on a broad field at random.

2. Draw one circle each round each of the rectangles.

3. Draw a circle round the center of the overall frame

4. Paint that part of each rectangle that lies outside circle no. 3 in a darker color.

Linguistically, these steps may read like instructions from a mathematics textbook, but for Channa Horwitz such instructions were simply part of a system that repeatedly gave her an opportunity to experiment and explore the most elementary of forms that surround us and define our perception – What happens if …? Chance was not something that interested her. Or rather she did not believe there was such a thing. “My work is based on the theory that the structure must only take effect for long enough to seemingly become chance. It does not actually become chance, it just seems to be.”

For decades, Horwitz developed her pieces almost completely out of the public eye, and with no active ties to the art scene. Over a period of 30 years her work went on show in not more than a dozen exhibitions. Although her interest in reduction and minimal aesthetics was definitely shared by her (male) contemporaries, and in the reception of her work today parallels are often drawn to artists such as Hanne Darboven, time was to pass before her oeuvre was accepted in the official art discourse. It was this year that KW Institute for Contemporary Art in Berlin hosted the first Horwitz solo show, titled “Counting in Eight, Moving by Color”. Major events such as the 55th Venice Biennale 2013 and the Whitney Biennale 2014 first brought Horwitz’ oeuvre to the attention of an international audience.

Despite or perhaps precisely because of this quasi-isolation Channa Horwitz chiseled tenaciously away at refining her universal language. Today, she shows us the world in all its complex simplicity.

STORM SALON FEAT. MINT CLUB NIGHT: Soumaya Phéline

As part of the exhibition STORM WOMEN SCHIRN is, together with MINT Berlin, hosting the STORM SALON at SCHIRN Café. Guesting December 10: Soumaya...

STORM SALON FEAT. MINT CLUB NIGHT: DJ rRoxymore

As part of the exhibition STORM WOMEN SCHIRN is, together with Mint Berlin, a network of women active in electronic music, hosting the STORM SALON at...