Our community is based on constant giving and taking. But where does art fit into this social framework?

“To refuse to give, or to fail to invite, is – like refusing to accept – the equivalent of a declaration of war; it is a refusal of friendship and intercourse.” Thus writes French sociologist and ethnologist Marcel Mauss in the introduction to his classic work “The Gift. Forms and functions of exchange in archaic societies” written in 1950. The giving and receiving of gifts, which can have material or symbolic value, is fundamental to coexistence as a community.

Marcel Mauss, Image via alchetron.com

What’s more: the systems of exchange that Mauss examined can be considered pre-monetary forms of trade, which were subject to specific moral and economic conditions and whose main features retain their validity even in our present-day societies. The most important finding is that a gift received must, under all circumstances, be reciprocated. After all: “It follows clearly […] that in this system of ideas one gives away what is in reality a part of one’s nature and substance, while to receive something is to receive a part of someone’s spiritual essence.” And: “Hence it follows that to give something is to give a part of oneself.”

Gifting attention

A song as a gift – in Lee Mingwei’s performance “Sonic Blossom”, opera singers approach individual museum visitors and dedicate to them a “moving song”, as the artist calls them, by Franz Schubert. The singers ask, “May I give you a gift?”, and if the visitor agrees then he or she is guided to a chair in the exhibition space to sit back and enjoy the performance. For Lee Mingwei, this is about participation, but also about sharing a fleeting moment and the gift-giver and the receiver enter into a fleeting relationship, with the receiver reciprocating the gift by giving his or her time and attention.

Schirn Interview. Lee Mingwei

For each gift that artist Micol Hebron distributed to participants at her lecture performance “Petting Zoo” at the Armory Show 2013 in New York, she requested something in return, for example a self-painted picture of a cute animal. While visitors caress ducks or sheep, Hebron gives a presentation on the concept of “cute”, and hands out presents – a total of 60 items during the 60-minute performance. Here, Hebron is investigating the potential for shared activities as much as the economy of giving.

Art, market, donated

“Take Me I’m Yours” is the name of the exhibition in which museum visitors can try out, use, buy or simply take away the exhibited works to their hearts’ content. In 1995, the show, curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist, was held for the first time in London, and in recent years it has been recreated in Paris and New York. The artist duo Gilbert & George donated badges, Hans-Peter Feldmann brought a collection of pin-up photographs from the 1940s, and visitors could help themselves to Felix-Gonzalez-Torres’ foil-wrapped peppermint sweets.

Félix González-Torres, Take Me I’m Yours, Image via thejewishmuseum.org

When the art show was held for the first time in 1995, the art market was in a slump. In “Take Me I’m Yours”, with a thoroughly critical gesture, the status of art is shifted away from sacred object towards mass product. Now the situation looks different, and record sums are once again being recorded on the art market. Nevertheless, the pressing question remains: How does our approach to art change when it is presented as merchandise, a souvenir, a gift? And how do we give back?

Giving and taking

When Marcel Mauss examined the function of giving, he identified that in archaic societies exchange took place not necessarily between individuals, but primarily between clans, tribes or families. Anything could be exchanged, not only goods and riches, but also courtesies, food, rituals, dances or festivals. The mutual giving and taking therefore does not only include moral and economic components, but also an aesthetic one.

Hans-Peter Feldmann, Take Me (I'm Yours), Image via socialmediafeed.me

Applying this to our present-day societies, Mauss identified that a large proportion of our morality still lies in that atmosphere of the obligation to give. We compete with one another with Christmas gifts, wedding celebrations or invitations, and feel obliged to “return the favor”. Yet what likewise remains is the feeling of pleasure in giving, in passing on something nice –in the hope that reward will come sooner or later.

5 questions for Mary Messhausen and proddy produzentin

With the performance "Thonk piece: Hungry for Stains", drag queens Mary Messhausen and proddy produzentin will open the exhibition COSIMA VON BONIN....

You Get the Picture: On Movement and Substitution in the Work of Lena Henke

The artist LENA HENKE already exhibited in the SCHIRN Rotunda in 2017. What are the secrets of her practice and where can you find her art today?

Lyonel Feininger and the Harvard Art Museums. Part 2

The Harvard Art Museums host the largest Lyonel Feininger collection in the world. The directors Lynette Roth and Laura Muir chat about Feininger’s...

Lyonel Feininger and the Harvard Art Museums. Part 1

The Harvard Art Museums host the largest Lyonel Feininger collection in the world. How did that happen and how was the relationship between the artist...

'Have yourself an experimental Christmas'

Bored of watching the same old Christmas films over and over again? Here are some of our favourite experimental films for the festive season.

Empathy, but how? Julia Grosse talks to Elisabeth Wellershaus

What role do empathy and emotions play in the cultural world of today and tomorrow? In the first part of the interview series, curator Julia Grosse...

The eventful history of plastic in design

The collection of the Design Museum Brussels consists entirely of objects made of plastic. No wonder, that some of the works in PLASTIC WORLD, which...

What does peace mean today?

In her work MARTHA ROSLER repeatedly addresses wars and protest movements. In conversation with peace and conflict researcher Thania Paffenholz we...

MOTHER IS MOTHERING. Lesbian motherhood in art

The role of the mother is often described, but most representations are still based on a heteronormative and patriarchal understanding. What does...

5 QUESTIONS FOR SEBASTAN BADEN

Starting July 6, the SCHIRN will be hosting an exhibition focusing on concept artist and pioneer of critical feminism Martha Rosler. Director...

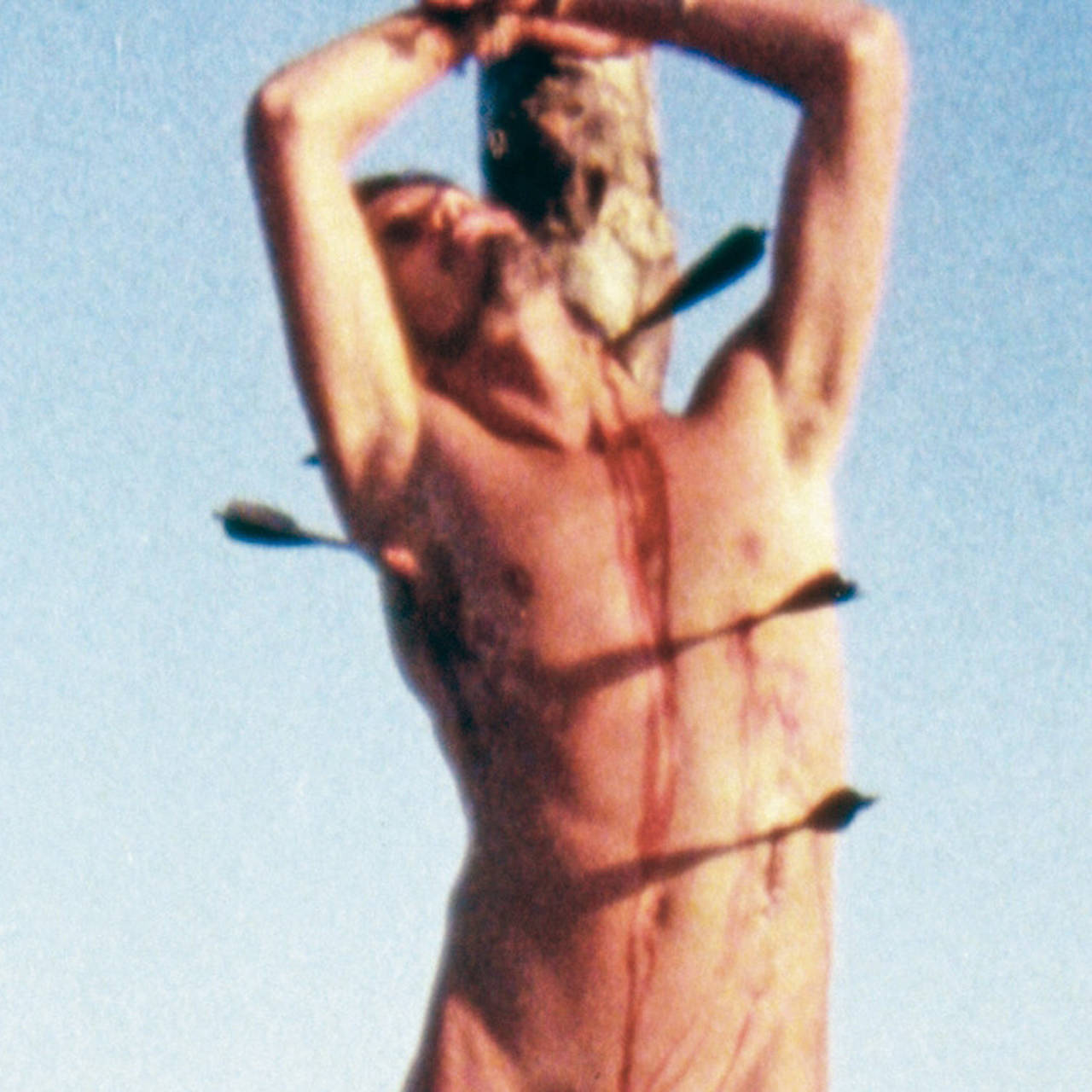

Queercoding in Art and Film: The Portrayal of St. Sebastian

While the sexualised portrayal of Saint Sebastian in Derek Jarman's feature film debut "Sebastiane" initially sparked social controversy in 1976,...

“History is not the past”: A conversation with Mirjam Wenzel and Meitar Tewel

The Judengasse in Frankfurt was once one of the most important centers of Jewish life in Europe. Today, its traces have been largely erased. The...