Since the early twentieth century, the manifesto has played, and continues to play, an important role in art. The catalogue accompanying the exhibition Infinite Jest presents several manifestos—between pious austerity and pure absurdity.

Who invented Britpop and Punk? When is a movie a film d’auteur? From music and the cinema to the visual arts – the attribution of a specific style, membership in a genre or a scene can occur in two ways: externally in retrospect, or self-defined in advance. In its rigorous form, the manifesto provides a particularly welcome medium for exploring the possibilities of delimitation.

Rien, rien, rien

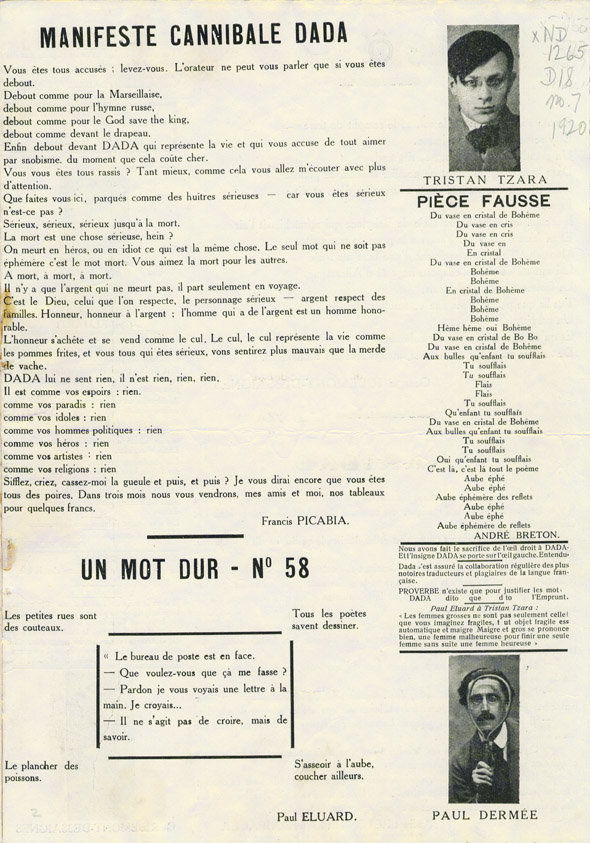

It is simply impossible to assign Francis Picabia to any one style: the painter, born in 1879 in Paris, experimented with a wide range of elements all his life – he initially engaged in Impressionism, was inspired by Cubism and Fauvism, and later discovered a brief passion for Surrealism. Picabia loved playing with ambiguity and did not think much of conventions. He was especially impressed by ideas of the Zurich-based Dadaists with their negation of existing ideals in art and society. In 1920, Francis Picabia had André Breton read his “Manifeste Cannibale Dada” at a Dada evening at the Théatre de la Maison de l’Oeuvre in Paris: after the speaker asks those in attendance to rise as if for the arrival of a king or the singing of the national anthem, he later solemnly states perhaps the most important core message of the manifesto:

“DADA lui ne sent rien, il n'est rien, rien, rien” [DADA doesn't smell like anything, it is nothing, nothing, nothing.]

What follows is a list of things that are likewise nothing: religion and hopes, paradises and idols, politicians and heroes. A nihilistic farewell to hierarchies, in its impish earnest an almost touching act of liberation for all of those who may have actually believed that this art current would represent only a new catalogue of rules and directives.

Political, Artistic, Very Personal

Just eleven years prior to that, someone else introduced the proclamation of manifestos: the French newspaper Le Figaro published Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’s “Futurist Manifesto,” which at first glance may resemble the Dadaist “God is dead” approach but which adopts a completely different tone in its politically biased pathos. Revolution, destruction, and violence: Marinetti’s Futurism plots the absolute. To the unsuspecting reader, his first manifesto could have definitely come across as a completely non-ironic proclamation of war – and yet Futurism would not smash and windows or set any buildings on fire but utterly without bloodshed break with social and artistic conventions. Yet a radically political claim nonetheless always pulsates in the background in all of the numerous manifestos later put forward. Whereby Marinetti chose the fitting audience in order to be able to cause an uproar in the nineteen-tens: he organized evenings in the provincial theaters of his home country during which he initially verbally abused the audience, so to speak – only afterwards were new Futurist manifestos read and did performances and art exhibitions take place.

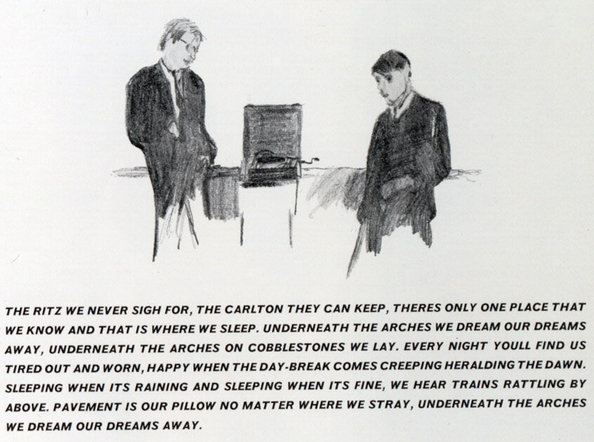

Futurism, Dada, later Fluxus – manifestos often served to define more or less loosely connected groups of artists. Contrary to their pious austerity, however, the solemn proclamations did not function as a restriction but opened up new space of creativity for individuals – not lastly thanks to the opportunities for (again) transgressing boundaries. In contrast, the artist duo Gilbert & George drafted what was almost a personal manifesto that defined the two Brits as a “living sculpture” but of course extends far into the public realm, where it develops its impact in the first place. The first and most well known of the smugly formulated “Laws of Sculptors” reads: “Always be smartly dressed, well groomed relaxed friendly polite and in complete control.”

The Attempt to Redefine Oneself

Of course, in none of the cases is the manifesto randomly chosen as a strictly formal matter. The outer corset is what allows dealing with a supposedly boundless world in the first place – or at least one experienced as such. Because although there were definitely still outer conventions to break for the Futurists and the Dada movement, the all-embracing upheaval was already clearly looming on the horizon: the new century, in which everything would change. The manifesto counters it with new rules – even if they only read not accepting any more rules in the future. Even the apparently most absurd among them is a kind of self-empowerment, an attempt to regain power over one's own self. Like children in fanciful role-plays who let on that the world operates just the same and not differently, the manifesto also opens its away into vile reality in what is almost nothing less than a magical way.