Else Lasker-Schueler appears to have distinguished less clearly between her own fantasy world and mundane reality than did many other artists of her time. An attempted biographical profile.

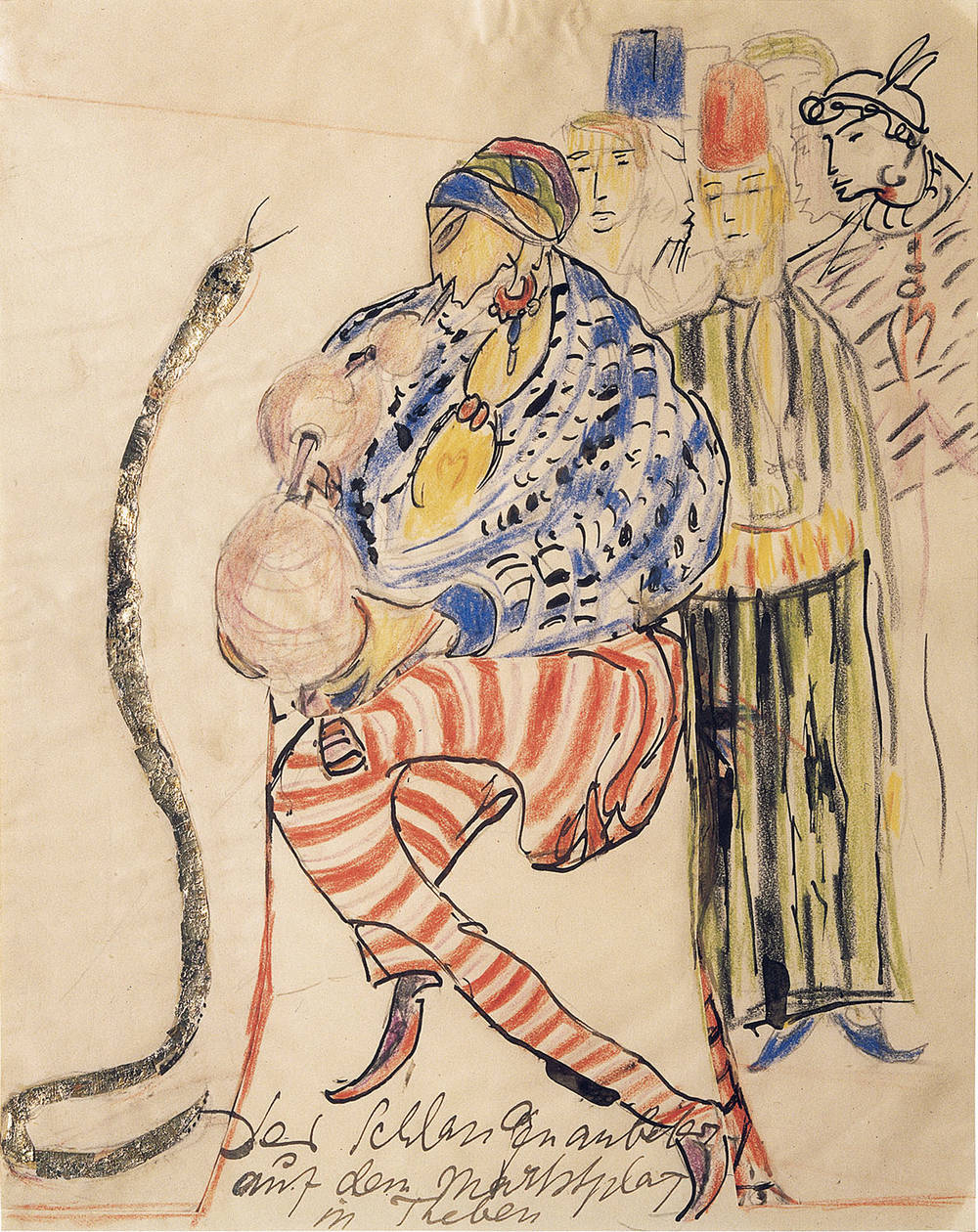

There are many anecdotes to relate about Else Lasker-Schueler, the famous German poet and artist, painter and self-proclaimed “Prince of Thebes”. This was a celebrity who was already able to read and write at the age of four, who gave all her lovers and companions imagined names, who was a permanent fixture in the “Café des Westens” during her time in Berlin, and who liked to play the flute in harem pants as a protagonist in her own Oriental cosmos.

All the above is probably true or in fact known fact, but it does not make the approach any easier. The nicely vibrant anecdotes are deceptive, pretend knowledge and insights, but cannot necessarily come good on this. At best, many of them together provide a framework but are less suitable as a comprehensive explanation. So if one initially sticks to the basic facts, then this is roughly the biography that emerges: Else Schueler was born in 1869, in what today is Wuppertal, the daughter of a Jewish banker. She was exceptionally intelligent and talented, dropped out of school at her own request, and was tutored at home from that point onwards. In 1894, she married physician Jonathan Berthold Lasker and moved to Berlin with him. The bond to her family must have been strong: When her mother died shortly before her wedding and her father followed a few years later, this amounted to “Expulsion from paradise” for Lasker-Schueler. She published her first poems at the age of 30, four years later she married her second husband Georg Lewin, upon whom she bestowed a new name: Herwarth Walden.

The world of her own imagination: Thebes in Berlin

In Berlin, Else Lasker-Schueler liked to frequent the “Café des Westens”, dreamed of herself in Oriental fairytale worlds and recorded them in vivid poems and later in small illustrations, which over time she expanded into large drawings. To pigeonhole Lasker-Schueler as belonging to a single movement, to attribute her work to a single school, must fail: Although she had numerous close artist friends, with whom she shared much, the world of her own imagination, however, seemed to exist autonomously from that of her outside world. No less than myriads lay between them. “Nothing remotely rational connected her to her surroundings and, in particular, to the masterminds of Dadaist iconoclasm; it was only the complete lack of bourgeois trappings that she shared with them, and not as an ideology, but rather as a natural impulse,” Walter Abendroth stated in 1966 in “Die Zeit”. Here again we find the stuff of legend and anecdote: Else Lasker-Schueler as a rebel, as a fantasty-bound poet, as an outsider, as a denier of pragmatic art and cultural politics.

“An old Tibetan rug” is probably considered one of her most famous poems, which was first published in Walden’s “Der Sturm” magazine and later, following an enthusiastic reception, again in Karl Kraus’ “Die Fackel”. There, Lasker-Schueler describes a love affair, tells of souls who are “woven together in the Tibetan rug”, and idolises the “lama-son on his musk-plant throne”.

Today either acclaimed or rejected

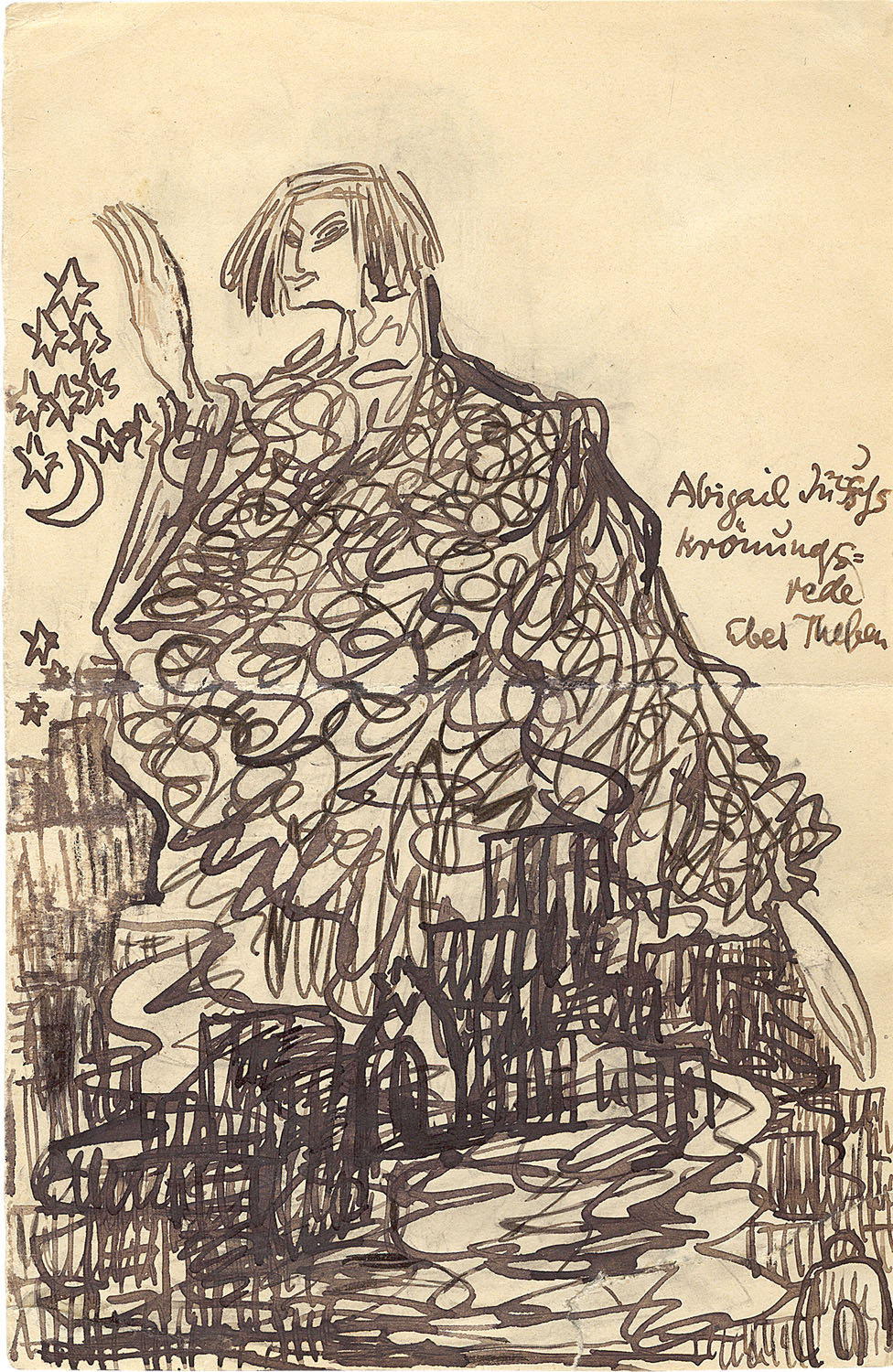

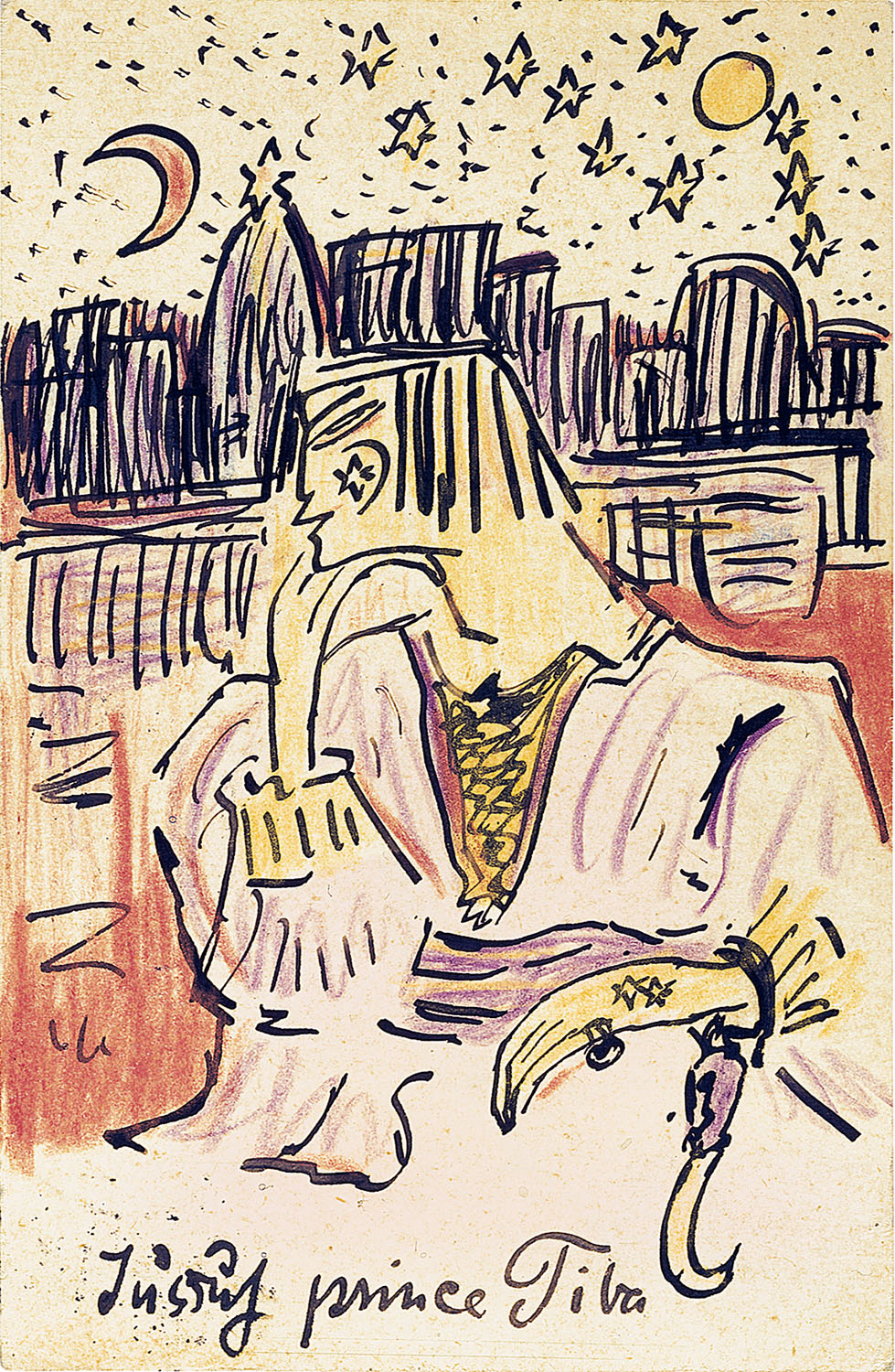

Drawing and painting was initially more of an accessory for Lasker-Schueler, illustration for her poems. She soon began to enjoy imbuing her literary cosmos with drawings: she brought Tibetan bridal couples, holding a monkey by the hand, to paper; in another illustration Prince Jussuff is riding through the desert on a camel. It is no coincidence that the prince resembles her, with his dark bob and harem pants, he is Else Lasker-Schueler’s alter ego and yet at the same time in a double meaning still also prince charming.

This demonstrative refusal to draw a line between private and artistic cosmos, between fantasy world and tedious reality, has been readily construed as showing Else Lasker-Schueler’s naivety, and and equally it has been either acclaimed or rejected. Instead of refuting this, one can understand the artist in precisely this deliberately chosen tradition: Literary scholar, Magnus Klaue, for example, has quite carefully identified kitsch and naivety as being characteristics of Lasker-Schueler’s poems in his essay “Poetischer Enthusiasmus: Else Lasker-Schülers Ästhetik der Kolportage“ – and uses these attributes to describe how seriously one should take the radical revolutionary content of her work, which sounds out the possibilities of art in a way that that many other barely dared.

Reality of life falls away behind the poetic

That the seemingly anecdotal side to her art should not actually be confused with real life or rather that art can never be completely reduced to tedious reality, is demonstrated by Else Lasker-Schueler’s escape into exile. In 1927, her beloved son Paul dies, a few years later she has to leave Berlin: in 1933, the artist emigrated to Zurich, since she had to fear for her life under the Third Reich. From there she undertook journeys to Jerusalem, which appears in her poems as a magical place quite out of this world. In 1939, on her third trip to Palestine, she was unable to return to Switzerland and remained there. She continued to write and speak of her (compulsory) homeland in picturesque images, yet the reality of life fell far short of the poetic.

What remains: a non-tangible moment, a lot of blanks. The readers must fill in the gaps themselves if they wish to follow the trail of Else Lasker-Schueler, Prince of Thebes and fantastic narrator. The great fascination of Else Lasker-Schueler’s poems and drawings, which can be understood as a gesamtkunstwerk, lie precisely in their readily allowing us to conquer them subjectively: She makes the viewer, the reader, her confidante, yet we must acquire this knowledge ourselves. Where the journey is headed is unclear, and it quite certainly won’t end up in the actual Orient, which, for all her ardent love, ultimately disappointed the fantastical imaginings of the involuntary expatriate.

Between life crisis and world war

Owner of the STURM gallery Herwarth Walden recognized her genius at an early date: Artist Marianne von Werefkin had a firm hold on the reins of the...

The gender question

The long road to equality: Do we need exhibitions like that of the STORM women to clarify the importance of women in art? An investigation in the...

Eyes front – the avant-garde

These days, the term “avant-garde” is applied to many things - SCHIRN MAGAZINE explains where it comes from and how it has changed down through the...