As part of its film series DOUBLE FEATURE, in March the SCHIRN is presenting a selection of works by the French artist Neil Beloufa. This will be followed by the screening of his favorite film, “Muriel,” by the late director Alain Resnais.

People easily lose track of things—in particular in times of globalization, difficult political conflict situations, and a prevailing sense of crisis—and perhaps for this very reason think they know what makes the world go round and, moreover, how politics is done. The extent to which those ideas can easily overtake reality in terms of pragmatic viciousness and cruelty is demonstrated in Neil Beloufa’s “La Domination du Monde” (World Domination) from 2012. In the nearly thirty-minute film, the protagonists appear to go through Hegel’s analysis that “nations that are involved in civil quarrels win repose at home by means of war abroad” in every way imaginable.

For “La Domination du Monde,” the artist (*1985 in Paris) had lay actors slip into the roles of leading personalities (presidents, interior and foreign ministers) of various nations and subsequently discuss political and geostrategic problems. Each team actually finds a promising solution, although doubt can be cast on whether it is in everyone’s interest. The solution to overpopulation or youth unemployment is war; the participants in the discussions even want to revive the economy or regulate the financial markets by means of war. While the identification of these solutions proceeds swiftly in the initial rounds of discussion, disputes keeps taking place over whether one should wage war against North or South America, Europe, Asia, or Africa.

Beloufa keeps us in the dark about whether the lay actors are following a script or improvising; what is apparent is the delight and the seriousness with which the actors decide on their solutions in the back rooms of power. What is evidently fictional thus creates its own reality. The artist time and again examines the relationship of tension between narrative and documentation and the blending of these opposites in his works, which is also the case in “Untitled” (2010). This work is based on the anecdote according to which terrorists hid themselves in a modern mansion near Algiers made completely out of glass that had been abandoned by its owner in the turmoil of the Algerian civil war in the 1990s. The terrorists hid there for three years, but against all presumptions left the mansion behind in perfect condition.

Beloufa was fascinated by this story, and so he traveled to Algeria to interview the homeowner, the terrorists’ staff, and local residents of the mansion. In “Untitled,” Beloufa has lay actors play the interviewees in a reproduction of the mansion made out of cardboard and photographic wallpaper, and speculate about why the terrorists sought out, of all things, a mansion made entirely out of glass as their hiding place, and how they spent their time there. The statements are in part contradictory, and for want of an actual witness do not serve for one second to discover the truth; rather, they give some indication of how myth formation continues to work in the modern world. The obvious film sets go a step further by creating the suitable setting in which conjectures and assumptions can develop a kind of independent reality.

Alain Resnais’s “Muriel,” which won the Sutherland Trophy of the British Film Institute in 1963, takes the involvement with fiction and reality even further by interviewing its protagonists with respect to the authenticity of their own lives. In what seems like an avant-garde montage, “Muriel” relates the story of the alienation of three individuals—Hélène, her stepson Bernard, and her early love Alphonse—from one another. Hélène wants to revive the relationship with Alphonse; however, within the scope of their renewed meeting both of them see themselves confronted with their self-delusion, illusions, and false memories, which makes any relationship between the two impossible. Due to the traumata he experienced during the war in Algeria, to the stepson, Bernard, the future as well as any genuine bond to others seems to be distorted, and thus any attempts by the three to begin to approach one another as individuals with their own past gradually fail.

Both the films by Alain Resnais as well as the works by Neil Beloufa communicate how a fictional narrative rises to become a reality in the everyday reality of an individual, and how such processes become possible in the first place.

Vestiges of the Past in the Present

For decades now, Anita di Bianco has been exploring corrections and rectifications in international newspapers. In the next DOUBLE FEATURE she will be...

Following Yaarborley Domeï

Belinda Kazeem-Kamínski’s video piece is dedicated to a letter written by Yaarborley Domeï. This rare testimony to a past time describes not only...

A Symphony of Transformation, Decay and Regeneration

Hybrid creatures with prostheses or organic forms jutting out of their bodies – in the upcoming DOUBLE FEATURE artist Eglė Budvytytė turns her...

Just What is a Patriarchy?

Can women help men to articulate their emotions? And what is the response to feminist statements in patriarchal structures? Julika Rudelius looks into...

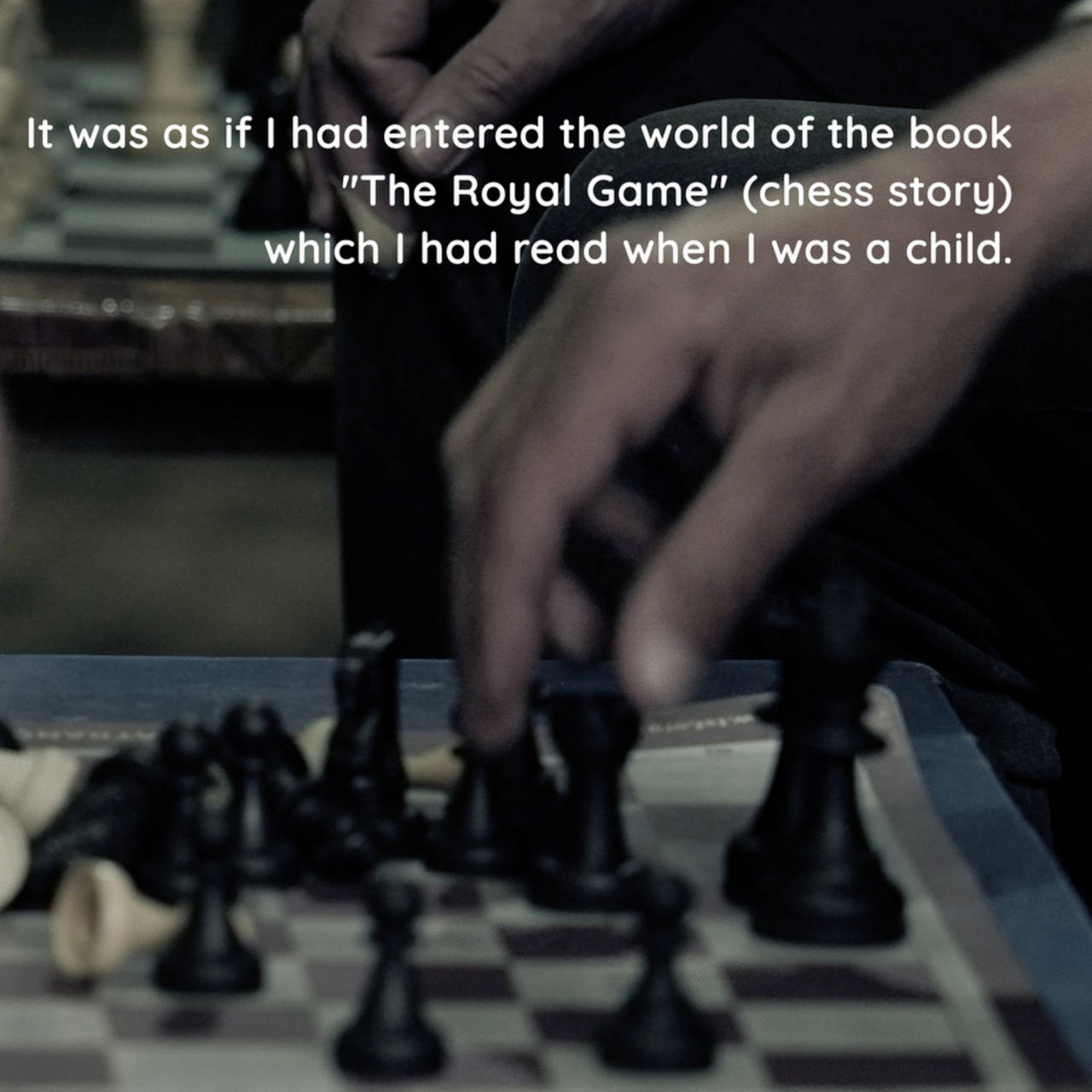

Chess Stands for Survival and Prison

In the upcoming DOUBLE FEATURE artist Pınar Öğrenci is screening her video “Aşît”, which was inspired by Stefan Zweig’s “The Royal Game”. She finds...

A poetic approach to the world

Solitude, subjective feelings, ineffability, desire, a poetic approach to the world and our surroundings – these themes were typical for the Romantic...

The Fabulously Strange World of Marianna Simnett

A maltreated piglet runs into a pond before finding itself in a surreal underworld and encountering dogs in latex costumes. In the DOUBLE FEATURE with...

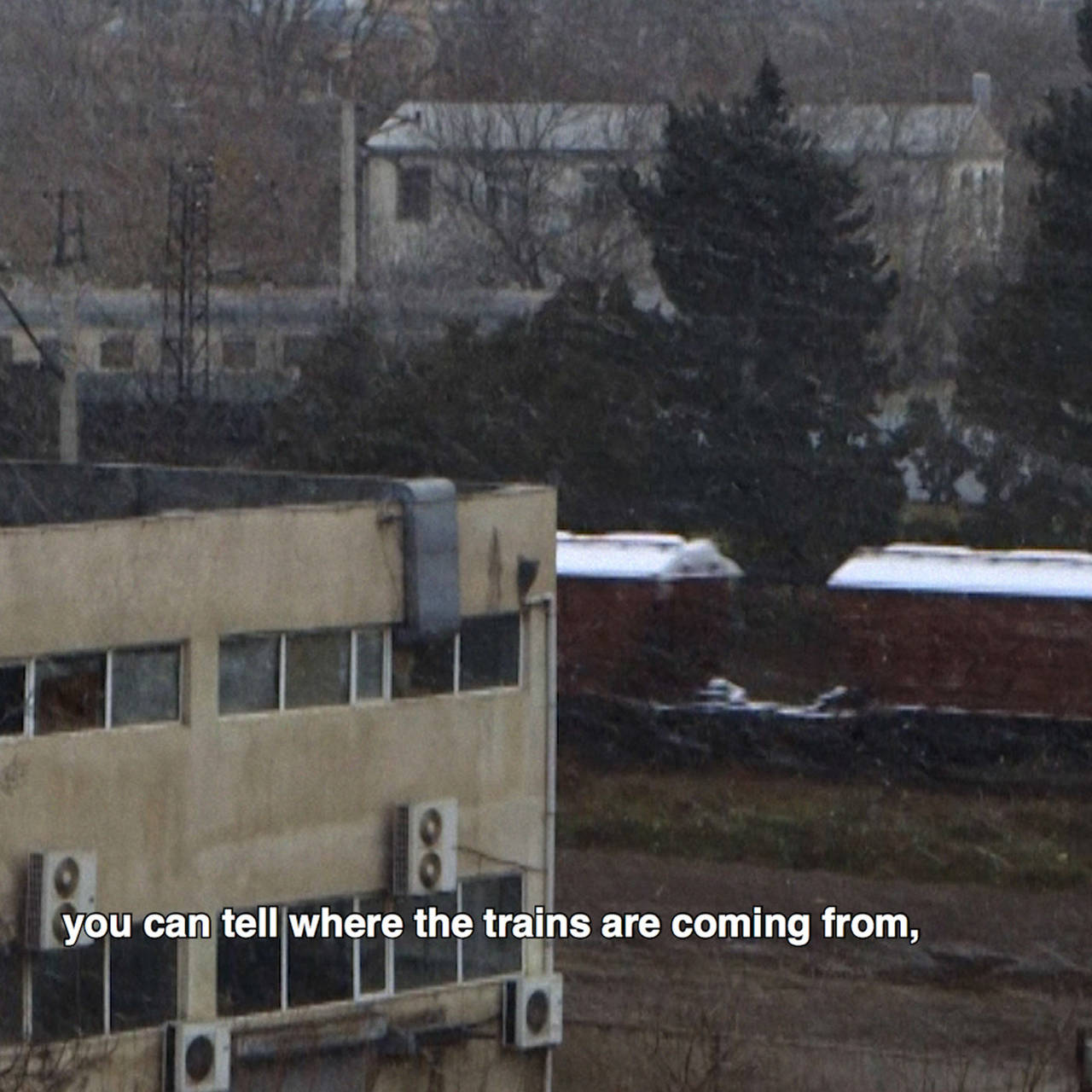

A search for traces along countless freight trains

In her video work “A State in a State” Tekla Aslanishvili addresses the simultaneity of war, political upheaval, and economic factors. The artist...

Forensic Archaeology. On Detective Work in Art

In the Geneva Freeport complex alone there are said to be round 1.2 million works of art (including Nazi looted art). The artist of the upcoming...

The blessing and curse of Nigerian tin mining

The Jos Pleateau in Nigeria was famous for its tin mining during the time of British colonial rule. In her video work “Plateau,” Karimah Ashadu...

About Pigeons and People

Yalda Afsah’s video work “SSRC” places the focus squarely on the relationship between humans and animals. For in the Secret Society Roller Club – also...

(Re-)Visiting Changsha

What if Roland Barthes had been a local tourist? In his new video piece “Sight Leak” (2022), Chinese artist Peng Zuqiang re-imagines the French...