On December 16, Canadian artist Melanie Gilligan will guest in the last DOUBLE FEATURE of the year.

Capitalism, that awkward and yet so signifier-laden Something, has in recent times managed the almost impossible: From the anarcho-capitalists of the Tea Party through to the middle classes that feel somehow betrayed by it, to the Social Democrats, who try to tame it, and the autonomous extreme Leftists who wish to overcome it: All of them call it by its name and try in the one or other way to use it to interpret the world – either for or against it.

While the one camp considers it a problem that we overly curb capitalism and believe the solution would be to give it complete free rein, the other thinks this would dissolve society. They are at most in agreement that the problem has in any case to be tackled at the global level, as the world of the 21st century is simply above all a capitalist one.

In “Self-Capital” (2009), a tripartite video piece made by Toronto native Melanie Gilligan (born in 1979), the issue is explored from a different angle. Here, the focus is not on human suffering within capitalist society, but the suffering of the global economy itself. The part of the latter is played by Penelope McGhie, who is sent as a particularly difficult case from one psychiatrist to the next owing to her post-traumatic stress disorder caused by a severe crisis.

The global economy permeates everything

In fade-backs we watch the personified global economy in a book store, joyously reading out economic terms: “industry clusters”, “chambers of commerce”, “creative industry”, “commercial”, “emerging markets” – the words “migrant workers” especially seem to trigger joy. Symptomatically, the crisis itself appears when words such as “workers”, “casual labor” or “wages” cause her to vomit rather than experience libidinous joy. In “Self-Capital”, the global economy simply pervades everything and in this way Gilligan has Penelope McGhie also play the roles of patient and psychiatrist, seller and buyer, and the sorely tormented psyche treated by a kind of body therapy.

In previous works, consisting of videos and installations, Melanie Gilligan has repeatedly addressed capitalist exploitation and the related social problems. Her attention was drawn to the roots this form of economy has in crisis in a Marx reading circle in 2005, and three years later, in the year of the major financial and subprime crisis, she brought out her video series “Crisis in the Credit System”, where she presented her conclusions from interviews she conducted in London’s banking world –in the form of a fictitious story. “Popular Unrest” (2010) amounts to a kind of sci-fi/horror TV series, again subdivided into five episodes. “Popular Unrest” takes place in a version of our world in which a global system – “The Spirit” – structures all personal and all economic interactions between humans.

The compulsion to ascribe a value to everything

One part of the plot revolves around a series of murders where people are stabbed to death by a knife that appears out of nowhere. At the same time, an inexplicable social phenomenon occurs, whereby people who do not know one another at all gather in smaller or larger groups and out of nowhere forge a strong emotional bond. A research group then tries to establish a link between such a group, the murder series and the quasi-entity “The Spirit”.

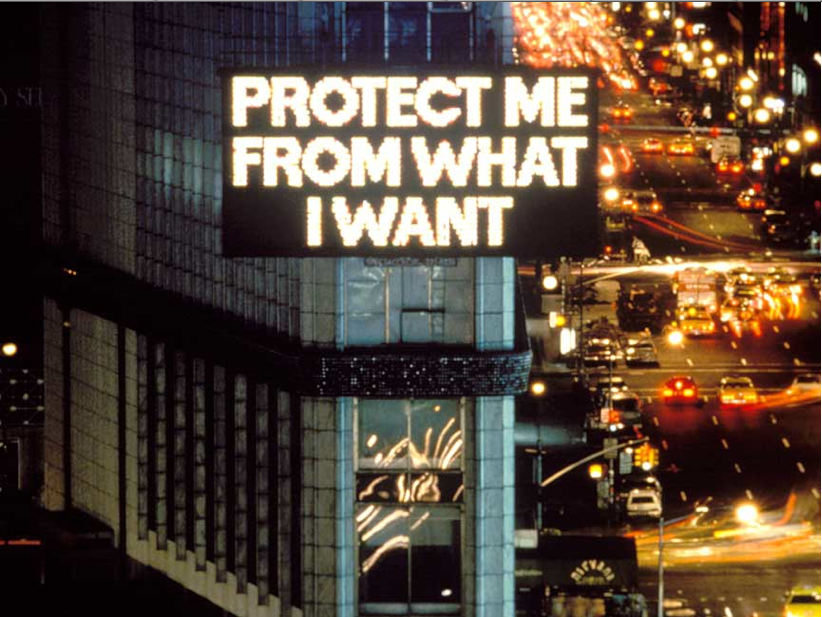

As in other pieces Gilligan also makes use of the currently very popular narrative format of series episodes, in “Popular Unrest” she combines the aesthetic of typical US TV crime formats, such as the CSI series, with elements of so-called “body horror”, the best-known proponent of which is US director David Cronenberg. Key to “body horror” is the representation of violent and painful changes to the body (usually through metamorphoses, maiming or mutation) that as a rule culminate in the body morphing into a new shape. The “Spirit” in “Popular Unrest” is described in terms generally used today to describe capitalist exploitation: it pervades everything, has the compulsion to compare each thing with everything else in order to ascribe a value to it, and in this way establish a certain order, or, as some would say, form of domination.

Psychological suffering turns into the terror of physical violence

The label “body horror” is also very applicable to Andrzej Żuławski’s film “Possession”, which came out in 1981. Shot in West Berlin, until it came out on VHS in 1999 it was only available in the US version, which had been cut by 45 minutes; in Germany it originally was not screened in movie theaters at all. The film describes the separation and bitter relationship struggle between Anna (Isabelle Adjani) and Mark (Sam Neill). At the beginning of the film, Anna leaves Mark and their small son in order (or so Mark believes) to live with another man. This is just the start of a story that becomes ever more bizarre and brutal, and the violence of the images is only topped by the grueling and incredibly impressive performances by both protagonists, especially by Isabelle Adjani. Or, as “Lexikon des internationalen Films” puts it poignantly: Żuławski succeeds in “turning an absurd theater of violence into emphatically moving arthouse cinema”.

Żuławski, who wrote the script during a painful separation, translates the private battlefield that the rupture of a relationship constitutes into the genre of horror film and in that setting transforms the psychological suffering into the terror of physical violence. This externalization of inner states is repeatedly to be encountered in Gilligan’s oeuvre, as her protagonists are always forced to experience physically the psychological effects of capitalist exploitation – be it in the form of psychological or physical dysfunctions or in the form of death.

Sigrid Hjertén: Radically Modern

She alternates seemingly casually between the role of mother and that of artist and is considered the pioneer of Swedish Expressionism: STORM artist...

Why revolution is no longer possible today

Why is the neoliberal system of rule so stable? Why is there hardly any opposition to it? Despite the ever greater divide between rich and poor?

Dinner is served: Daniel Richter as chef de cuisine

Artist Daniel Richter likes to use metaphors from the kitchen – SCHIRN MAGAZIN explains why he has prepared his new series of pictures at the SCHIRN...