In Double Feature, British artist Beatrice Gibson addresses the value of money.

How did it go again in the song by critical Pop band Ja, Panik? “Nothing’s about me or you honey, it’s all about the angst and the money.” Apart from the obvious implications of these lines they also refer above all to value as a property of money, which assigns value to things and people, making everything comparable in figures.

But what exactly should a value be? How exactly do you ascribe a value to something, no matter what it is? What form of abstraction does this require? Economists have forever racked their brains about this topic and posited various theories on value, with that by Karl Marx remaining one of the best known.

Solo for a rich man

In her video piece “Crippled Symmetries” (2015) British artist Beatrice Gibson (b. 1980) addresses all of this: money, abstraction, music. Music? Initially, you hear cellist Anton Lukoszevieze relating an anecdote: Lithuanian artist and co-founder of the Fluxus movement, George Maciunas, went to America to try and make money with art – and he failed.

Afterwards we hear a composition by Maciunas: “Solo for a rich man.” Here, in place of classic music notes the artist noted abstract directions: shaking coins, dropping coins, striking coins, wrinkling paper money, fast ripping of paper money, slow ripping of paper money, striking paper.

Greed, hope, desire, trust

“Crippled Symmetries” interweaves various strands of the plot with one another. Like Gibson’s previous works “Solo for a rich man” (2015) and “F for Fibonacci" (2014), it is inspired by William Gaddi’s book “JR,” a satire in which a young man and a composer build up a financial imperium. In “Crippled Symmetries” the cellist Anton Lukoszevieze and a nameless young man seem to represent the characters of the book – the camera accompanies them driving round in a limousine, shopping in a supermarket, making music – and we also see recordings of a music workshop lasting several days, which the musician had organized for children.

Finally, we see Lukoszevieze in downtown London talking in recurrent scenes with a banker (Oliver Botes) about money, music and naturally value per se. What is the defining property of money? Exchanging, says the musician – trading, swapping. But music is something different, something abstract. The banker guides the discussion to the value of money: Basically, money is something very vague and essentially merely represents something very human, namely greed, hope, desire, trust. Just like music, adds the financial expert.

In these late-capitalist times

And indeed, money is not only paper; it has an ascribed value, which seems to be transferred to the goods we pay for with money. The invisible, in other words concealed value, alters its manifestation at will. You could apply the same principle to art, and to music in particular, for in composition the artist’s thoughts and sensations are transformed into notations, and for the performer these represent instructions relating to his instrument, which in turn through the performance create a materialization of the composer’s original intention.

In times in which everyone is talking about late capitalism and neoliberalism Gibson seemingly refers in “Crippled Symmetries” to the basic requirements of modern life, to something that is also deeply anchored in the cultural output of humanity: abstraction, as the transfer and communication of specific content from one level of meaning to another.

The project is a catastrophe

As her favorite film, Beatrice Gibson chose “Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One” (1968) by American documentary film director William Greaves. Superficially, the experimental film seems to document actors during rehearsals. However, “Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One” quickly turns out to be a meta-documentation in which Greaves introduces various narrative levels with the help of three cameras. One camera films the interaction of the actors, the second camera includes shots documenting the instructions by the director and the first camera crew, while the third camera captures the second film crew and the surrounding hullabaloo, in other words the set as a whole and onlookers.

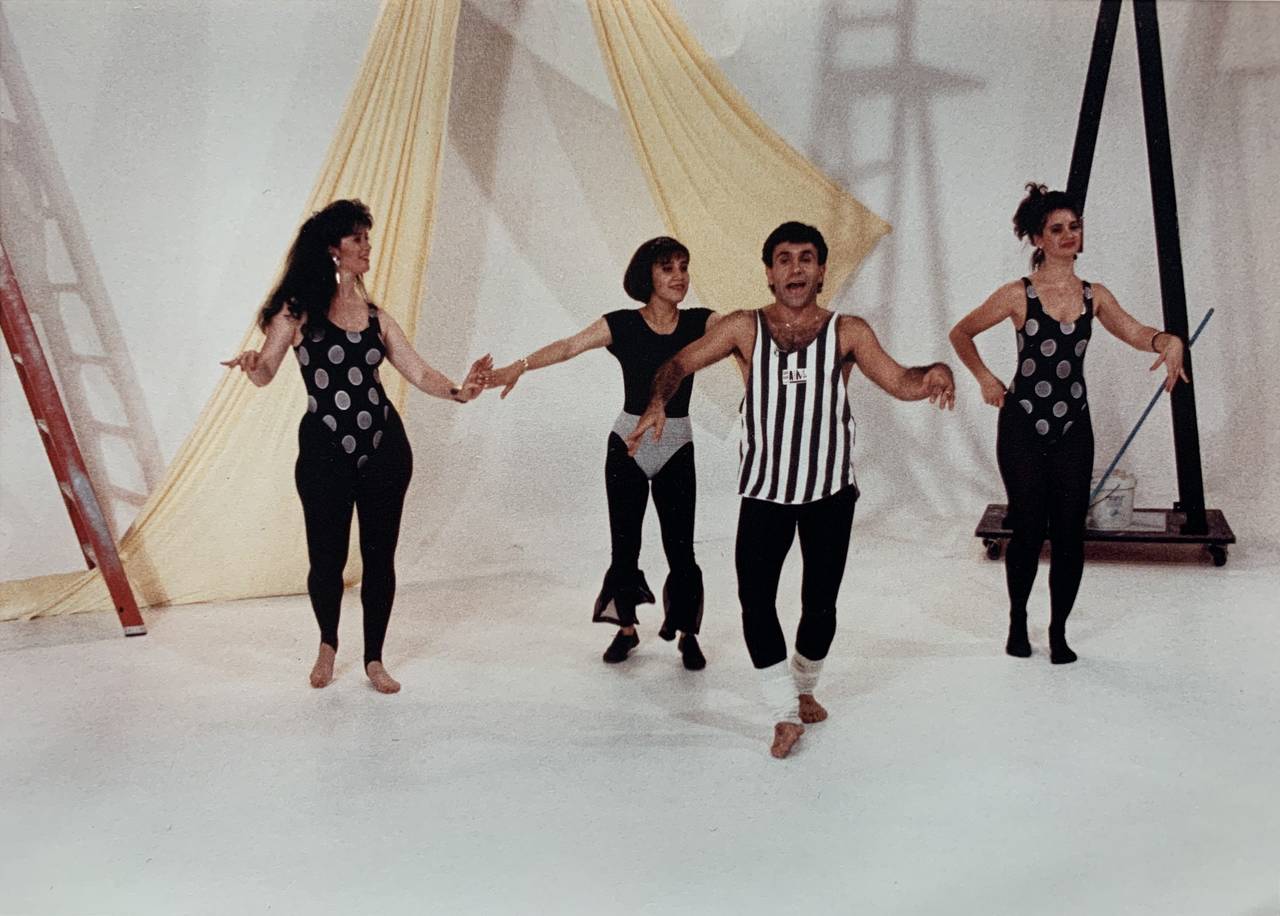

Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One, William Greaves, 1969, Image via pzwart.nl

Greaves carries to extremes his game of mixing documentation and acting by asking the film crew to record discussions in which the technicians and assistant directors argue about the directing style, content and form of the film – naturally in the director’s absence. The project is a catastrophe and Greaves is a sexist who has no idea what he is doing, we then hear from some members of the film team, while others claim to recognize a higher meaning in Greaves’ approach to work.

Acting as an everyday phenomenon

For many years the meta-documentation remained a favorite among critics, but was unknown to the public; as nobody wanted to produce the film it was only shown sporadically in museums or in screenings Greaves organized himself. In 1993, Steve Buscemi saw “Symbiopsychotaxiplasm” at the Sundance Festival and subsequently teamed up with Greaves and Steven Soderbergh to get the film released; it was even followed by a sequel in 2003. Fortunately – you want to say, for “Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One” is a fascinating document years ahead of its time and not only reflects the production conditions and possibilities of film documentation, but also acting as an everyday social phenomenon, way ahead of reality TV and the self-presentation of individuals in mass media.

Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One, William Greaves, 1969, Image via pzwart.nl

At the mercy of waiting

Artist Bani Abidi is dedicated to the dark absurdities of everyday life. In her video work "The Distance from Here" bureaucracy takes over and waiting...

“Please don’t make a film about Godard!”

A film about filmmaking sounds a bit meta. But Kristina Kilian’s video work takes us on a ghostly journey through Godard’s Germany after the fall of...

Black is not a Color

In a film series, Oliver Hardt combines the themes from Kara Walker’s work with the perspectives of Black people in Germany. In conversation with...

How do we Remember?

In which places does history become visible? And what do we remember at all? Maya Schweizer begins her search for clues in the sewers and slowly feels...

Film highlights from South and North America

How can we break with the power relations of the past and create a decolonial future? A look at the representation of Indigenous women in film.

Must See: The World of Gilbert & George

Eccentric, fascinating, repulsive, entertaining and full of symbols: “The World of Gilbert & George” is a collage about the artifice of everyday life...

Spring is coming, and so is Magnetic North

For the first time in Germany, principal works from Canada’s major collections are on view at the SCHIRN. At the same time, the exhibition examines...

A Revolution in Iranian Dance

After the Iranian Revolution a nationwide dance ban was issued. It was subverted by smuggled video cassettes of dancer-in-exile Mohammad Khordadian,...

How to perform painting

This is perhaps the best way to describe the work of video artist Angel Vergara: Art history meets pop culture, the artist himself appears as a...

About the resistance of our bodies

Hypnotic dances and hybrid beings in cyberspace: Video artist Johanna Bruckner transforms the human body into digital matter.