In the exhibition “Diorama. Inventing Illusion” artists question staged visions and reconstructed realities. In modern everyday culture, this phenomenon is already reflected in “reality TV”.

We’re all familiar with those scenes in reality TV: artificial dialogue, staged moments amid antiquated interiors made up of plush beige sofas and fake-wooden Ikea furniture. TV papers and remote control placed neatly on the coffee table. As the camera pans to the right, it shows the wall unit, bulky and in bright wood. Small decorative articles fill its compartments, framing the 49” LED television set. The protagonists are draped on the sofa; tired, empty gazes staring towards it. Their bodies are limp and frozen in place. They appear lifeless, as deliberately arranged as objects on show in a display window. As if looking into a peep box in the form of our TV set, we see our own living rooms in these real-life situations. The diorama of exhibited realities.

The exhibition „Dioramas“ recently opened at Palais de Tokyo, Paris, is shining a light on a cultural history of vision with the Diorama in its centre. From October 6 onwards the exhibition will be presented at the Schirn in changed shape. The first diorama opened under Charles M. Bouton and Louis J. M. Daguerre in 1822 in Paris. At that time, dioramas were large-format, up to 22 x 14 meters, with canvas backdrops painted as landscapes. These were translucent, so that they could be illuminated from behind. Using elaborate light effects, these dioramas shed light on scenarios of a romanticized, generally picturesque idyll. Visitors sat in a darkened room, and every 20 minutes the landscape theme changed to the sounds of orchestral music, similarly to the first silent film presentations.

Raoring stags in the museum

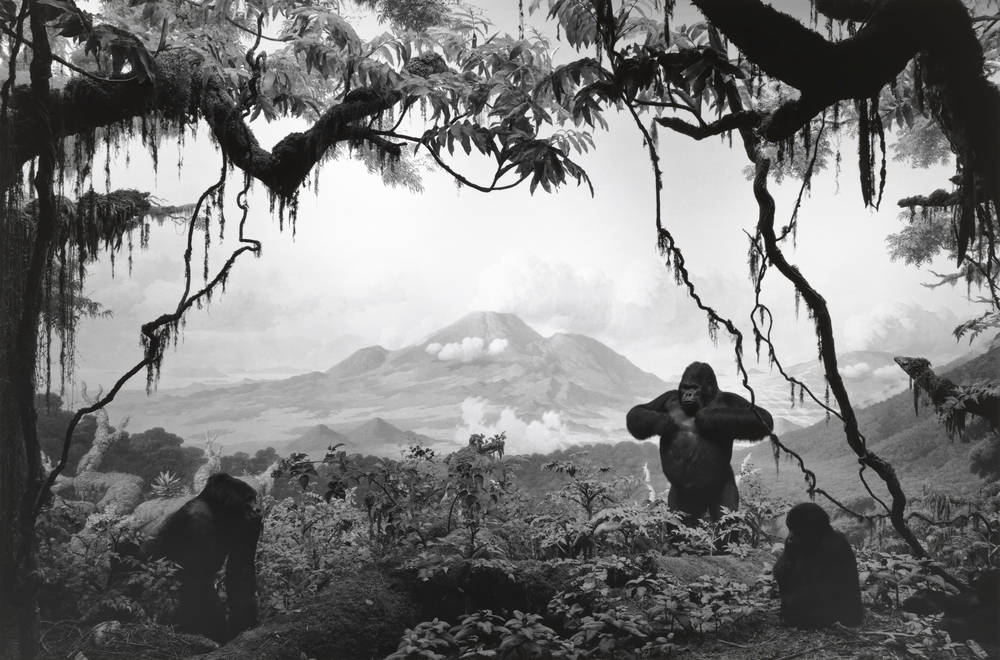

It was only later that the diorama came to refer to large display windows in which the “natural” habitat of animals was recreated in model form. The stuffed animals are positioned as if performing their “typical” actions: a bear going after a fish, a roaring stag, a polar bear greedily eyeing up a seal. The exhibition space of natural history museums was generally darkened as visitors wandered from one window on the world to the next.

Staged and constructed realities similar to those of a diorama are reflected in modern everyday culture in so-called “reality TV”: In the case of both media, the observer looks into a box, which is illuminated from the inside out as the sole light source. The time of day and location in the peep boxes break with that of the outside world. Within a diorama situations appear romanticized; in reality TV, the recipients experience strong feelings, for example by sharing vicariously in the lives of the protagonists.

Parody of reality

Worlds in miniature. Realities that accumulate the attributes and gestures of the physical world. A perception of reality based on interpersonal interaction. The protagonists of the milieu behave according to expectations of their roles. Here, the framework conditions construct a reality that is so perfectly coherent that it is already another parody of the physical reality.

Canadian photo artist Jeff Wall has long been included in the canon of contemporary photography. He became known for his large-format back-lit photos that permit his photographs to be illuminated in a similar way to the dioramas of Daguerre and Bouton, whose meticulous staging is also referenced in the painstaking composition of his worlds within the world. Wall, who is an art historian, is inspired by everyday life and then reconstructs these impressions subsequently for his photo tableaus. Hence these supposedly chance excerpts of reality are actually planned and realized down to the smallest detail: Light, individual gestures, clothing, even the natural environment become part of his formational act. When Wall builds his photographed worlds himself, he is addressing the deliberate construction of these realities.

Complete deception

For over 20 years artist Hiroshi Sugimoto, who was born in Tokyo in 1948 and lives in the USA, has been photographing dioramas. The motionless scenes permitted a long exposure time so that razor-sharp shots could be created. In his “Dioramas” series, the image section corresponds to the borders of the photographed display window, hence observers would struggle to identify in which museums Sugimoto found and photographed the dioramas. Through the delineation of the photographed section and the omission of the surroundings, the deception is complete: The photographed ensembles could be mistaken for snapshots of real nature – but then they wouldn’t have that clear, rigid lifelessness, the moments presented would not be staged quite so perfectly. In his works, Sugimoto addresses constructions of reality and in doing so raises questions about the formation of reality and illusion, authenticity and apparent reality.

Jeff Wall via Public Domain Dsign-magazin

Be it in the diorama, in reality TV or in the Jeff Wall photographs– the protagonists repeatedly make an indispensable contribution to the brief narrative of the ensemble. Since these compositions merely offer information about what is shown and the stories end precisely where the framework of these worlds cuts them off, it is only through the recipients that stories can be attributed to them. And, are the filmed milieus of reality TV not also simply a product of a prop master or screenwriter?

Revealing constructs

Alongside the aforementioned artists, the SCHIRN’s “Diorama” exhibition includes works by Mark Dion and Isa Genzken. Countless artists of the 20th and 21st centuries address questions of staged vision, illusion and reality in their works. They thus move within the current discourses surrounding constructions of life-realities and hold up a constructed, artificial reality against one that is fixed – a reality that is so similar to ours that it reveals our supposedly firm regularities as a social construct.

How Hip Hop sings about its dead

Death plays a large part in Hip Hop. The tragic early passing of legends such as Biggie Smalls and Tupac, not to mention rising superstars like...

5 questions for Mary Messhausen and proddy produzentin

With the performance "Thonk piece: Hungry for Stains", drag queens Mary Messhausen and proddy produzentin will open the exhibition COSIMA VON BONIN....

HIP HOP IS BLACK CULTURE – NOT THE OTHER WAY AROUND

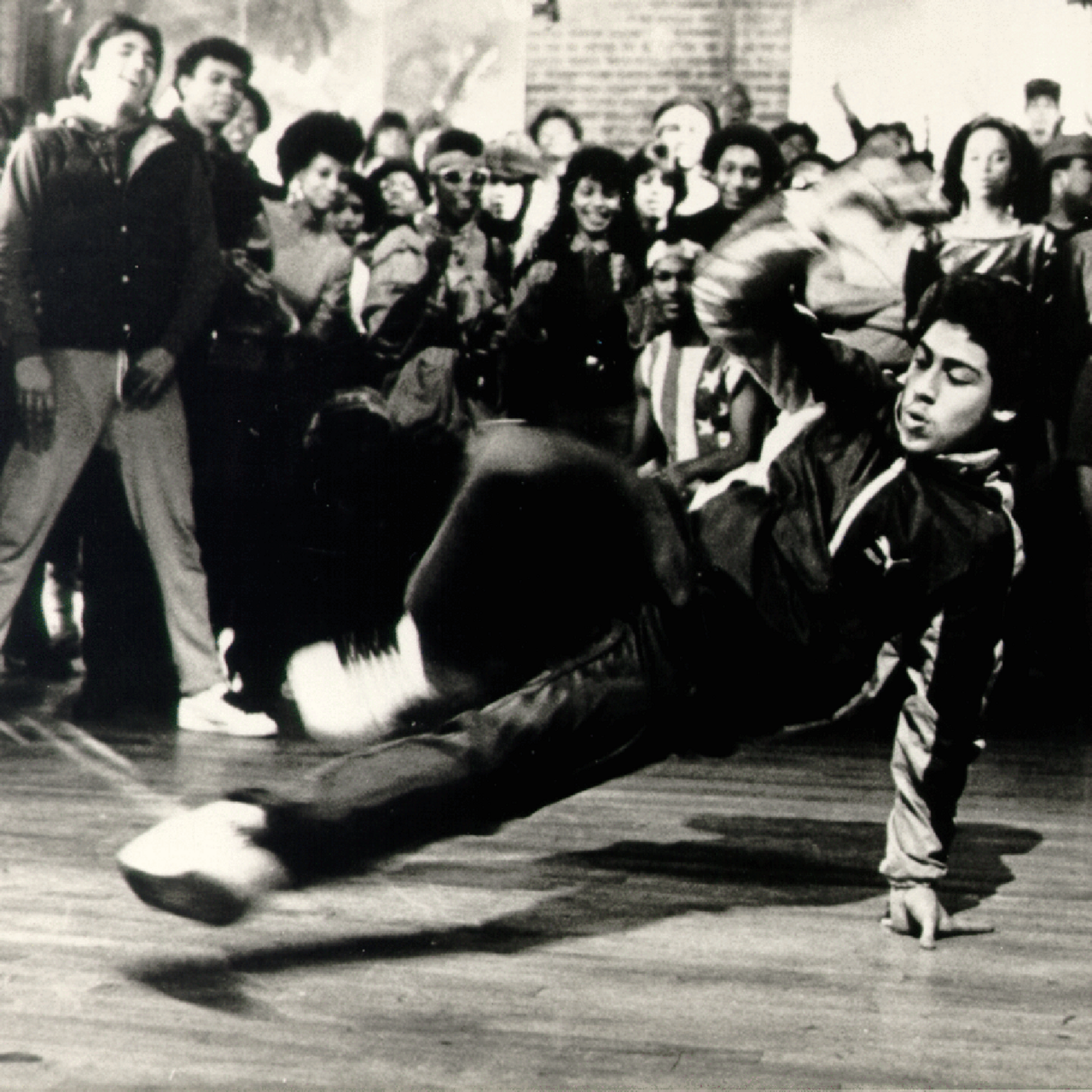

Hip hop’s 50th birthday is an occasion for us to listen to some old records and mixed tapes and to look back at the most important hip hop films of...

Now at the SCHIRN:COSIMA VON BONIN

The SCHIRN is showing a unique presentation of new and well-known works by COSIMA VON BONIN until June 9.

SHALLOW LAKES – plumbing the depths

In the SCHIRN’s rotunda, MELIKE KARA is presenting a series of sculptures that are reminiscent of bodies of water or small lakes. So, what’s this...

When subculture becomes mainstream – a balancing act

Regardless of whether it is hip hop, techno, or the queer scene: It is not unusual for the aesthetics of countercultures and subcultures to morph into...

Now at the SCHIRN: THE CULTURE: HIP HOP AND CONTEMPORARY ART IN THE 21ST CENTURY

Coinciding with the 50th anniversary of the birth of hip hop, the SCHIRN dedicates a major interdisciplinary exhibition to hip hop’s profound...

Julia Feininger – Artist, Caricaturist, and Manager

Art historians can tell us a lot about LYONEL FEININGER, but who was Julia Feininger and what legacy did she bequeath to the world of art?

Lyonel Feininger and the Harvard Art Museums. Part 2

The Harvard Art Museums host the largest Lyonel Feininger collection in the world. The directors Lynette Roth and Laura Muir chat about Feininger’s...

Five good reasons to view Melike Kara in the SCHIRN

From February 15, the SCHIRN presents a new site-specific installation by Melike Kara in its public rotunda. Here are five good reasons why it's worth...