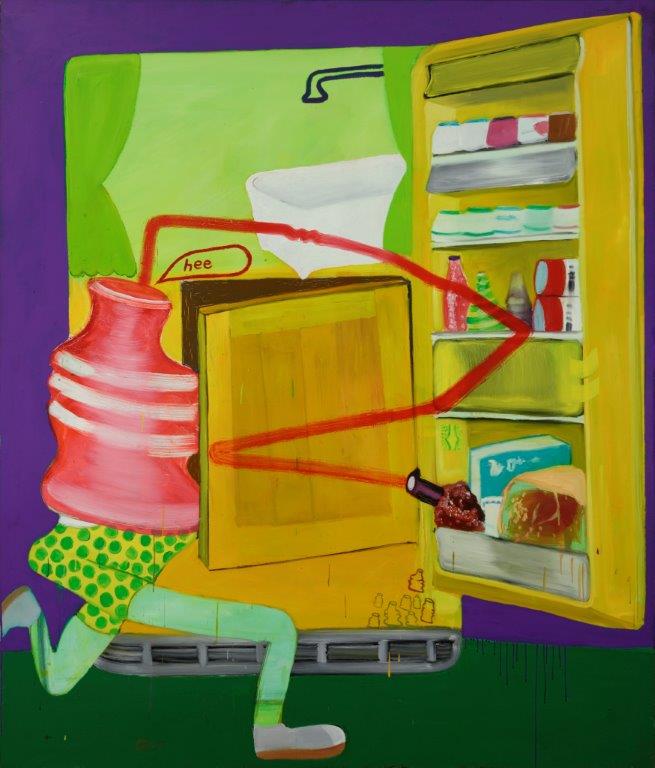

Deformed bodies and faces, irreverent themes, kitsch, consumerism and criticism. The paintings that are generally deemed “bad painting” are as diverse as the artists responsible for them.

Great was the indignation when, in 1948, Belgian artist René Magritte painted a series of pictures for his first solo show in Paris, paintings quite unlike his previous output. However, with his “periode vache”, provoking his viewers was not his only consideration. He also intended to call into question both his own work and painting in general – a subject also taken to task less than 30 years later by the “bad painter” of the United States.

The term “bad painting” was coined by US curator and critic Marcia Tucker at the end of the 1970s, when she used it for an exhibition of figurative painting. A style of painting that differed considerably from those known previously. It is simultaneously amusing and scandalous in its cynical worldview and its pitiless scorn of the conventions of art – it is a criticism of painting using the painter’s tools.

The limitations of painting

By opting for the kind of painting that is not “correct”, that is even “bad”, these artists challenge the tried-and-tested medium, questioning its boundaries and attacking its principles. And indeed, what can painting still achieve in the debates conducted by modern society? Where do its boundaries lie? The “bad painter” ignored these boundaries with raised brushes and a twinkle in their eyes – they are at once passionate champions of painting and its greatest critics. By including all kinds of “sources of irritation” in their pictures, overloading them with motifs, distorting faces and working with thick, dirty brushes, they reference the shortcomings of the medium.

Two decades before art critics started to include the term “bad painting” in their canon, Peter Saul had cheerfully explored the boundaries of good taste by mixing elements of Surrealism, comics and Abstract Expression into his pictures. Pop Art and Funk Art, the latter a type of art to be found principally in late-1960s San Francisco, also served as the inspiration for his work, illustrating his criticism of the consumer society in the United States and of the ostensible “purity of art”.

Go with the flow

However, the “bad painter” are not only to be found in the United States. At around the same time as Saul, Danish artist Asger Jorn produced his “modifications” by painting on top of pictures from flea markets (principally corny images of a stag at bay) with thick brushstrokes in primary colors, but without completely masking the actual subjects of the paintings. In this way he lends a familiar motif beloved of the kitsch-loving bourgeoisie a contemporary touch. “Why reject the old if it can be modernized with a few brushstrokes? This lends a hint of topicality to their old culture. Move with the times and, at the same time, be distinctive. Painting is finished. All we now need to do now is to deliver it the coup de grace. Redirect it. Long live painting,” he wrote with a twinkle in his eye in the introduction to an exhibition catalogue in 1959.

Asger Jorn via Public Domain derstandard.at

Germany, too, witnessed a series of “bad painter” at the beginning of the 1960s – Jörg Immendorf, A.R. Penck, Sigmar Polke and Georg Baselitz who, with their raw, awkward-looking paintings, turned the art world of the time upside down. Baselitz, who had escaped from East Germany in 1958 and had no desire to submit to new and restricting rules, painted himself his own freedom with mud, dark colors and obscene motifs – a freedom for which he had to pay when a number of his works were impounded.

Vulgar and impious

It is this cheerful cross between kitsch and serious themes, archetypes, the traditions of the history of art and that which is anything but art, the vulgar and impious which characterizes most of the pictures by the “bad painter”. After all, the word “bad” does not refer solely to the poor quality of the relevant artists’ painting styles but also includes the element of “terrible”, “rude” and “ugly” in their choice of motifs – however, not in the sense of the kind of “aesthetics of the ugly” which looks for an inherent beauty even in repugnant objects, but in its blunt, pure form. That pristine form which, right up until the present day, artists repeatedly search for, hunt down, reject and redefine – but without their fascination ever diminishing.

5 questions for Mary Messhausen and proddy produzentin

With the performance "Thonk piece: Hungry for Stains", drag queens Mary Messhausen and proddy produzentin will open the exhibition COSIMA VON BONIN....

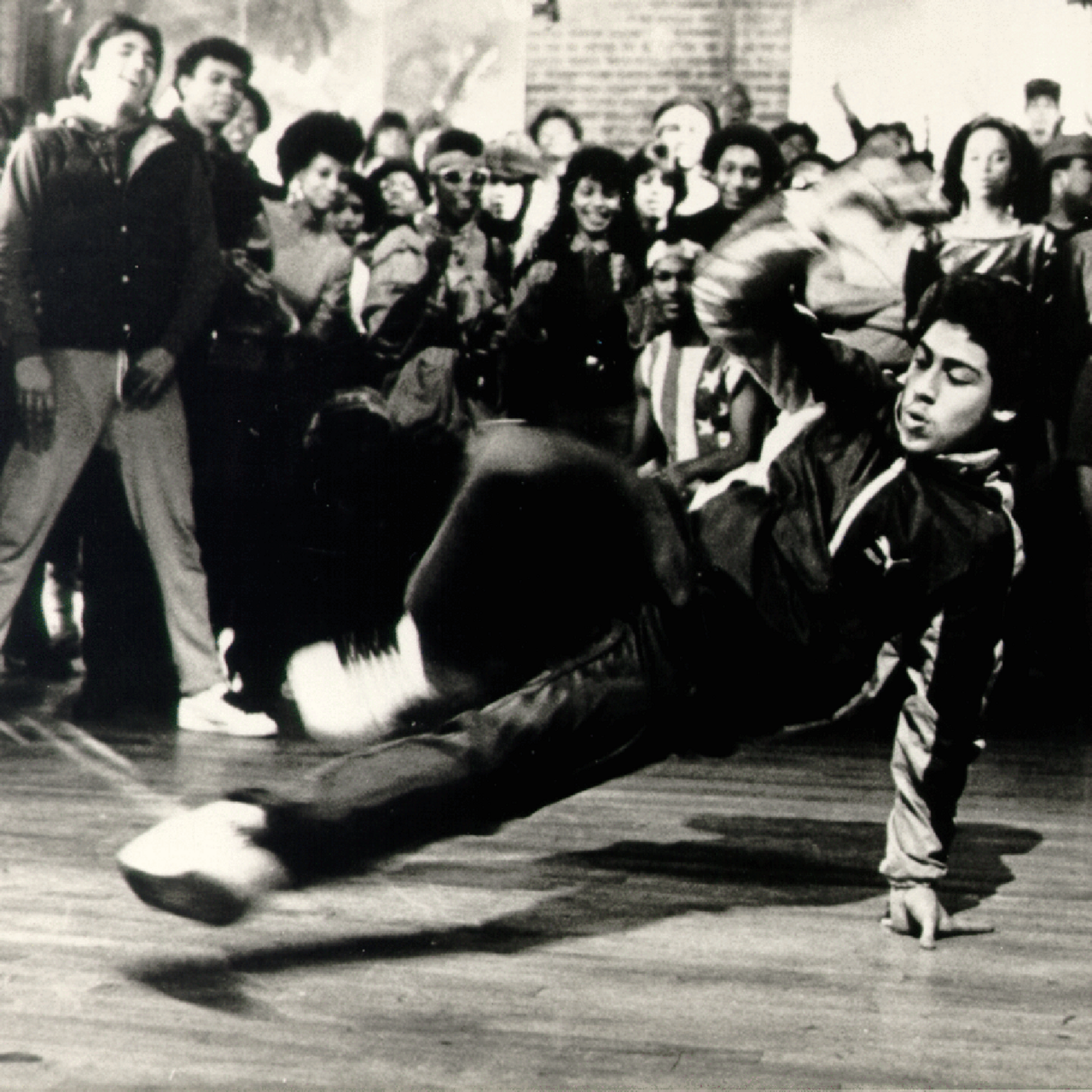

HIP HOP IS BLACK CULTURE – NOT THE OTHER WAY AROUND

Hip hop’s 50th birthday is an occasion for us to listen to some old records and mixed tapes and to look back at the most important hip hop films of...

Now at the SCHIRN:COSIMA VON BONIN

The SCHIRN is showing a unique presentation of new and well-known works by COSIMA VON BONIN until June 9.

SHALLOW LAKES – plumbing the depths

In the SCHIRN’s rotunda, MELIKE KARA is presenting a series of sculptures that are reminiscent of bodies of water or small lakes. So, what’s this...

When subculture becomes mainstream – a balancing act

Regardless of whether it is hip hop, techno, or the queer scene: It is not unusual for the aesthetics of countercultures and subcultures to morph into...

Now at the SCHIRN: THE CULTURE: HIP HOP AND CONTEMPORARY ART IN THE 21ST CENTURY

Coinciding with the 50th anniversary of the birth of hip hop, the SCHIRN dedicates a major interdisciplinary exhibition to hip hop’s profound...

Julia Feininger – Artist, Caricaturist, and Manager

Art historians can tell us a lot about LYONEL FEININGER, but who was Julia Feininger and what legacy did she bequeath to the world of art?

Lyonel Feininger and the Harvard Art Museums. Part 2

The Harvard Art Museums host the largest Lyonel Feininger collection in the world. The directors Lynette Roth and Laura Muir chat about Feininger’s...

Five good reasons to view Melike Kara in the SCHIRN

From February 15, the SCHIRN presents a new site-specific installation by Melike Kara in its public rotunda. Here are five good reasons why it's worth...

Lyonel Feininger and the Harvard Art Museums. Part 1

The Harvard Art Museums host the largest Lyonel Feininger collection in the world. How did that happen and how was the relationship between the artist...