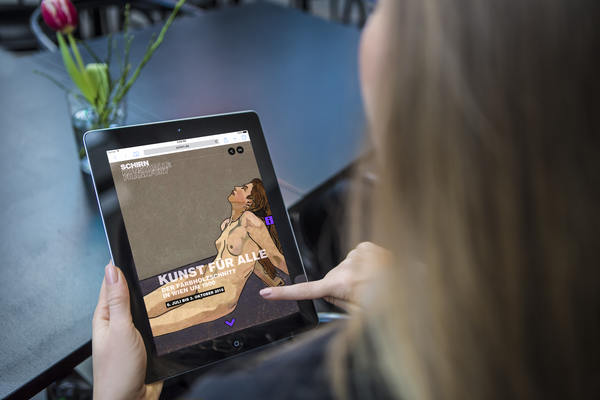

The SCHIRN presents for the first time an overview of the color woodcut in Vienna at the beginning of the 20th century.

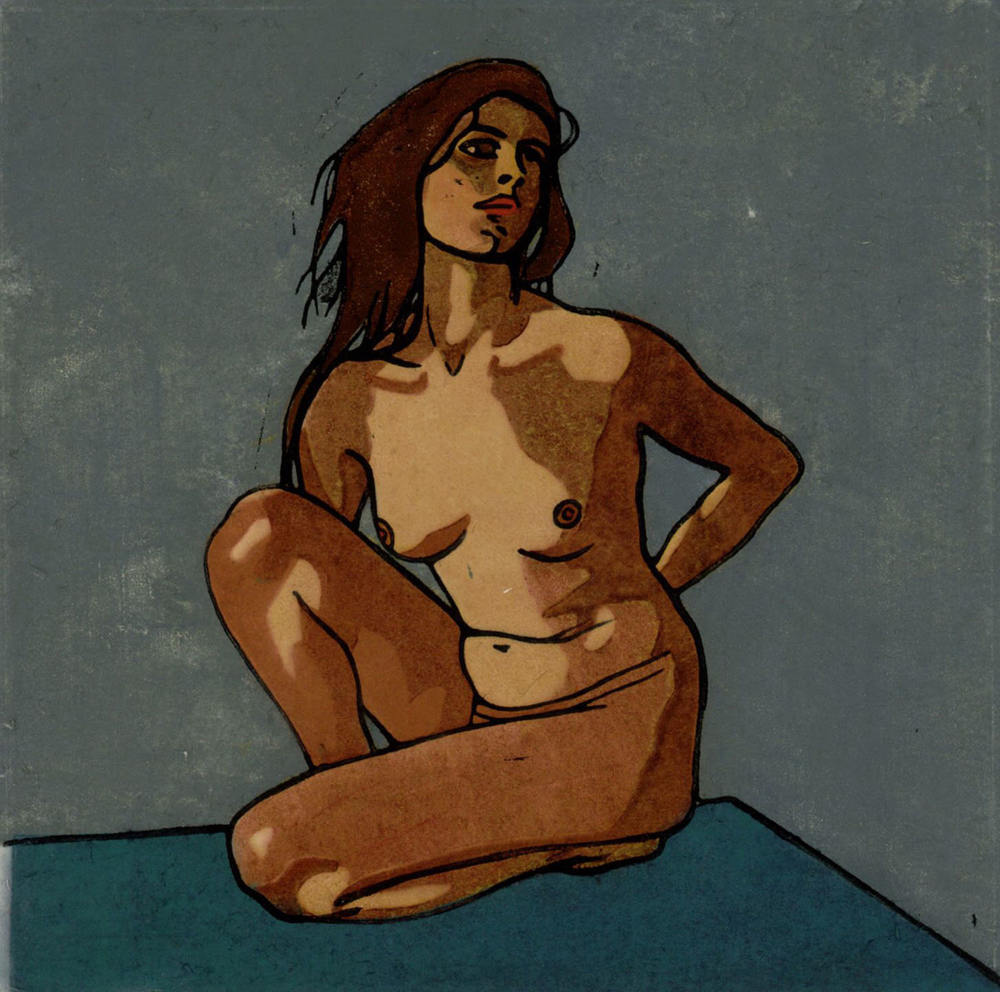

This exhibition is a first. The woodcut is one of the oldest printing techniques known and reached its zenith during the Middle Ages with Albrecht Dürer. Over the centuries the technique was increasingly forgotten, only to be rediscovered quite suddenly throughout Europe in a trend-setting development at the beginning of the 20th century. This was also the case in Vienna, where numerous artists, including a remarkable number of women, breathed new life into the color woodcut. From July 6 to October 3, 2016 the SCHIRN is dedicating a major, long overdue exhibition to this previously largely neglected phenomenon. Some 240 works by over 40 artists – also employing related techniques such as linocut and block printing – give an impressive overview of the subject and demonstrate for the first time the full extent of the aesthetic and social achievements of the color woodcut in Vienna around the turn of the last century.

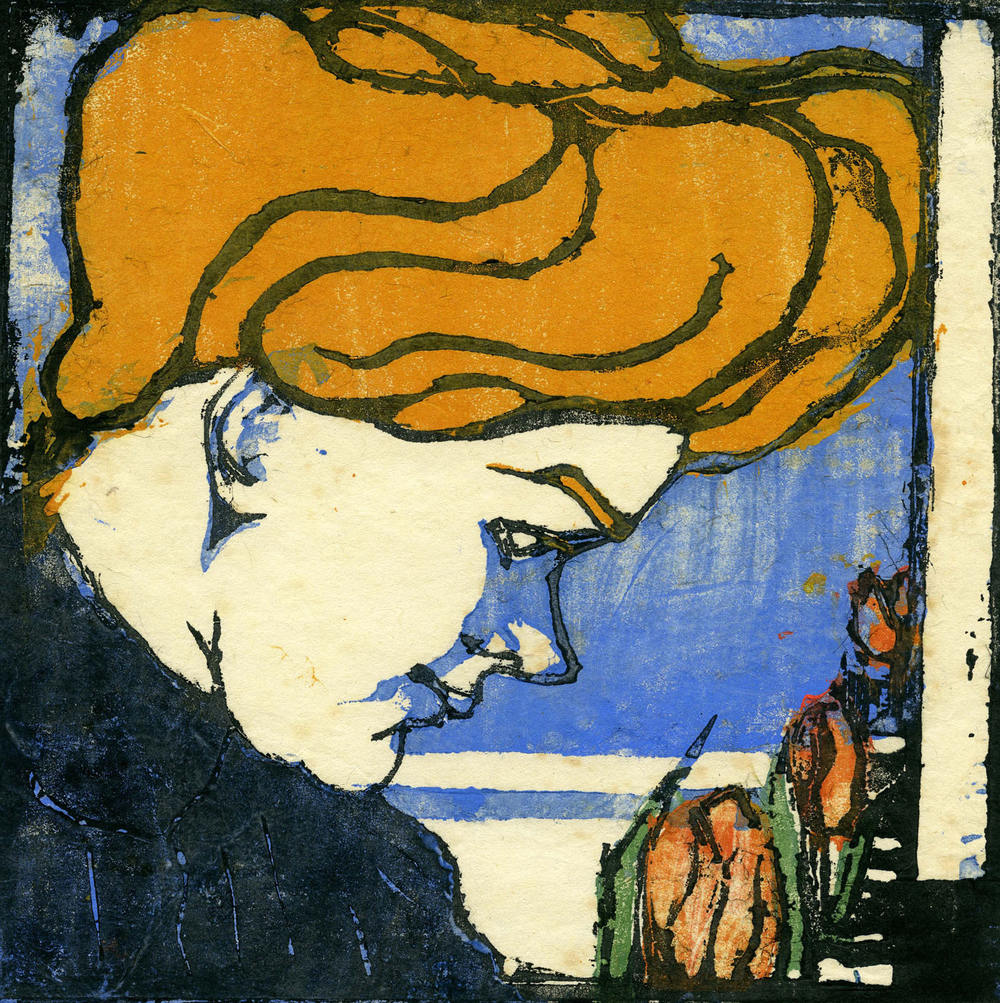

The presentation examines the remarkable enthusiasm with which not only established painters, but also newcomers devoted their attention to the color woodcut during a short but all the more intensive golden age between 1900 and 1910 in Vienna. Among them were members of the Vienna Secession whose names are still familiar today, such as Carl Moll and Emil Orlik, as well as artists who have been almost forgotten like Gustav Marisch, Jutta Sika, Viktor Schufinsky and Marie Uchatius. The latter were all students of the Wiener Kunstgewerbeschule (College of Applied Arts), which was particularly popular among talented young artists. They were fascinated by the technical and formal possibilities of the traditional printing technique, which offered the artistic imagination tremendous freedom. It considerably influenced the emergence of a modern pictorial language at the beginning of the 20th century with its characteristic outline drawings and its stylizsed planar representational style.

Moreover, thanks to its affordable prices even for original prints, the color woodcut opened up the previously elitist art market to a broad public. Within the social reformist movement “Kunst für Alle” (Art for All) it encouraged a lively discussion about authenticity and originality on the one hand as well as encouraging artistic creativity beyond the so-called “ivory tower” on the other – topics which have lost nothing of their relevance to this day. The extent to which the color woodcut contributed to a concept of art which aimed to encompass all aspects of life, can be seen in this exhibition. It is assembled in cooperation with the Albertina in Vienna and includes numerous loans from Viennese museums and institutions as well as from estates and private collections.

The golden age of the color woodcut in Vienna around 1900 was decisively influenced not only by the creative milieu, but also by social changes as a whole. This historical context forms the starting point of the exhibition. The nucleus of the rediscovery of the color woodcut lays in the Vienna Secession, a group founded in 1897 by Gustav Klimt, Koloman Moser, Max Kurzweil and others. It soon developed into the most influential association of fine artists in Vienna and represented the new artistic spirit of the age which broke with the backward-looking historicism of the era of the Vienna Ringstrasse.

In their famous association building the Secessionists presented highly acclaimed exhibitions, of which three in particular were very important for the color woodcut in Vienna: the VIth. Exhibition (1900) as a witness of the Reception of Japonism which was crucial to the development of the woodcut; the XIVth. Exhibition (1902) with its catalogue of original graphics – woodcuts printed from original plates; and the XXth. Secession Exhibition (1904), which dedicated its own room to the contemporary Viennese woodcut for the first time. A highlight of the exhibition programme in Vienna was the Kunstschau, organised by Klimt and other artists in 1908, in which almost the entire Viennese color woodcut scene was represented. Many of the works on display there are now being presented together in the Schirn for the first time.

Two magazines were equally important for the establishment of the color woodcut in Vienna. The first was the association journal published by the Secession with the programmatic title Ver Sacrum (Latin for “Sacred Spring”), in which 216 color woodcuts appeared between 1898 and 1903 in a total of six volumes. The second was the Jugendstil magazine Die Fläche (The Plane), which only published two issues, but which assembled numerous color woodcuts and examples of allied techniques such as lino cuts and stencil printing in the second issue in particular.

The publications issued by the Gesellschaft für vervielfältigende Kunst (Society for Duplicating Art) were widely circulated. The society itself was very highly regarded within the framework of the “Art for All” movement, which was gaining in importance at the time. The latter disseminated the view that art should become common property even beyond élite circles and that the distinction between “high art” and the so-called “minor arts” should no longer apply. For many supporters of the popular movement the color woodcut provided an answer to the conflict between modern art, social legitimation and general accessibility. Every year the Society distributed annual portfolios with original graphics among its members.

The woodcuts they contained – of which an important example forms part of the Schirn exhibition – were the work in most cases of artists from the Wiener Kunstgewerbeschule (Vienna College of Applied Arts). At the beginning of the 20th century, alongside the Secession, it formed the second centre of Viennese modernism and was very popular among up-and-coming talents because of its pioneer role in the support of a reformed applied arts scene. The school was especially important for women because they were admitted there to study art without restrictions; its graduates included Nora Exner, Nelly Marmorek, Jutta Sika and Marie Uchatius, amongst others. The central focus of the Secessionists, who taught here, especially the professors Koloman Moser and Josef Hoffmann, was the penetration of all aspects of everyday life with art. In this way they moved close to the increasingly important “Art for All” movement.

How Hip Hop sings about its dead

Death plays a large part in Hip Hop. The tragic early passing of legends such as Biggie Smalls and Tupac, not to mention rising superstars like...

5 questions for Mary Messhausen and proddy produzentin

With the performance "Thonk piece: Hungry for Stains", drag queens Mary Messhausen and proddy produzentin will open the exhibition COSIMA VON BONIN....

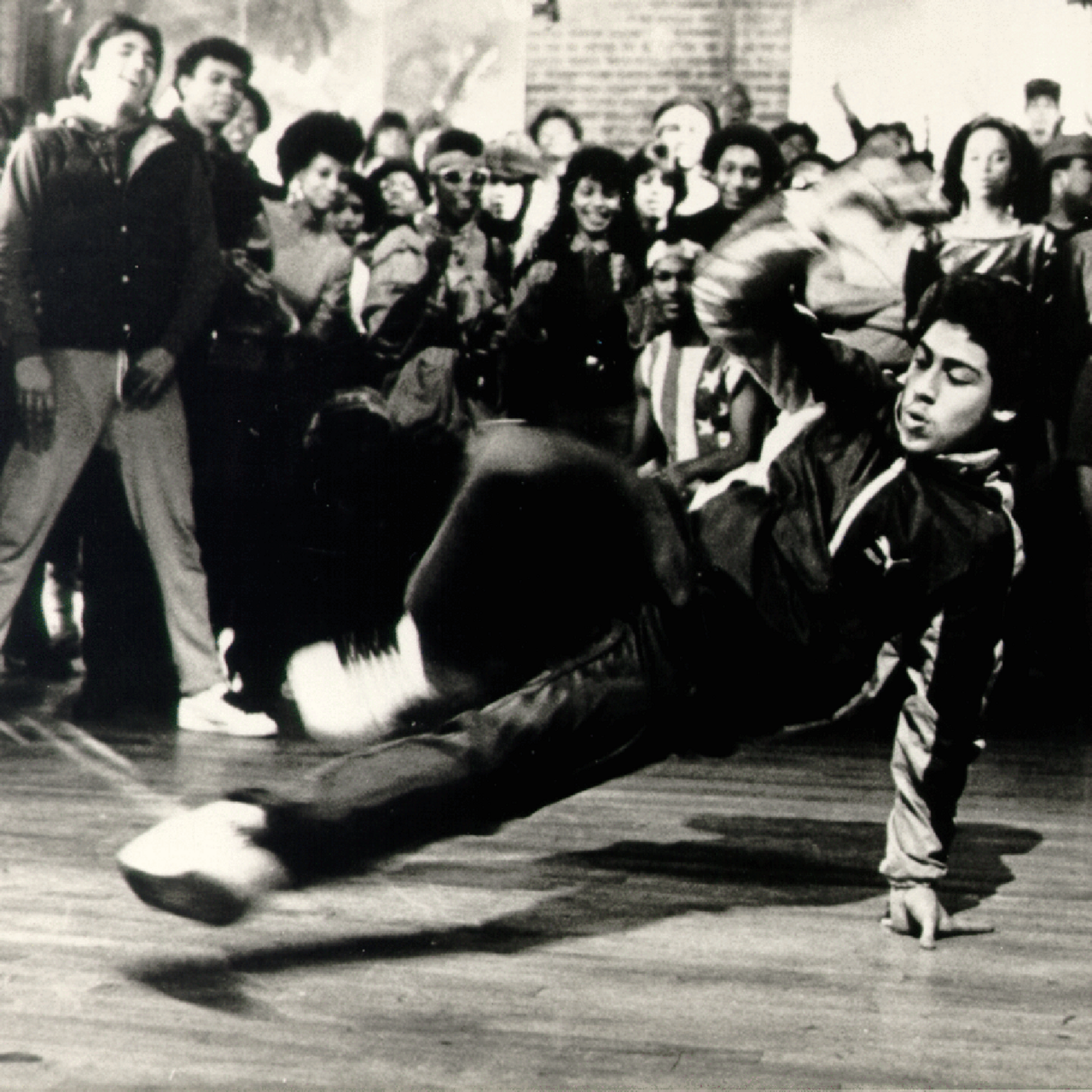

HIP HOP IS BLACK CULTURE – NOT THE OTHER WAY AROUND

Hip hop’s 50th birthday is an occasion for us to listen to some old records and mixed tapes and to look back at the most important hip hop films of...

Now at the SCHIRN:COSIMA VON BONIN

The SCHIRN is showing a unique presentation of new and well-known works by COSIMA VON BONIN until June 9.

SHALLOW LAKES – plumbing the depths

In the SCHIRN’s rotunda, MELIKE KARA is presenting a series of sculptures that are reminiscent of bodies of water or small lakes. So, what’s this...

When subculture becomes mainstream – a balancing act

Regardless of whether it is hip hop, techno, or the queer scene: It is not unusual for the aesthetics of countercultures and subcultures to morph into...