Or: What stories does a studio tell us about the artist? Artist Jeanne Mammen's apartment in Berlin is a great example of the close interweaving of art and history.

Picture this: an apartment in a historical old building with two light-flooded rooms, ceilings up to six meters high, and original wooden floors in the middle of the elegant Kurfürstendamm boulevard; in the immediate vicinity are various jewelers, expensive yoga clothing brands, an Apple flagship store and – inevitably – a branch of Deutsche Bank.

Yet what sounds like THE lucrative investment property for international real estate companies has not yet been converted into a law firm, dental practice, or a mere object of speculative investment. Rather, the home and studio of artist Jeanne Mammen (1890–1976) was taken over by Berlin’s Stadtmuseum in 2018 and has since been withdrawn from the real estate market for the time being. The studio has barely changed since the artist’s death. Only the many original works had to be replaced by replicas for insurance purpose and, most importantly, conservation reasons, but more on that later.

The studio therefore remains in the state in which Jeanne Mammen left it when she died in 1976. That’s 46 years ago, when the Berlin Wall was still standing, people still paid in deutschmarks, there were no mobile phones (let alone the Apple store nearby), kebabs had yet to begin their conquest of Berlin, rents were affordable, and the Berghain was still a combined heat and power plant. If you come across a macrame work in the dark hallway, then you can be sure that it wasn’t the result of a DIY tutorial. And so it is all the more absurd that behind all these well-restored, gleaming façades lies a rather modest place like this.

When Jeanne Mammen first rented the studio on April 1, 1920, with her sister Mimi, there was no toilet, no bathroom, and no kitchen – a state that wouldn’t change for the next 102 years. Before 1920, the rooms served as the workplace of photographer Karl Schenker. The fact the sisters were now going to live there does not seem to have prompted the landlord to provide such comforts as a private toilet. The first few years must have been a precarious but magnificent Bohemian period for Jeanne and Mimi, during which they produced commercial artwork for various clients and captured the idiosyncrasies of their contemporaries in caricatures for political magazines. But the good times were to come to an abrupt end.

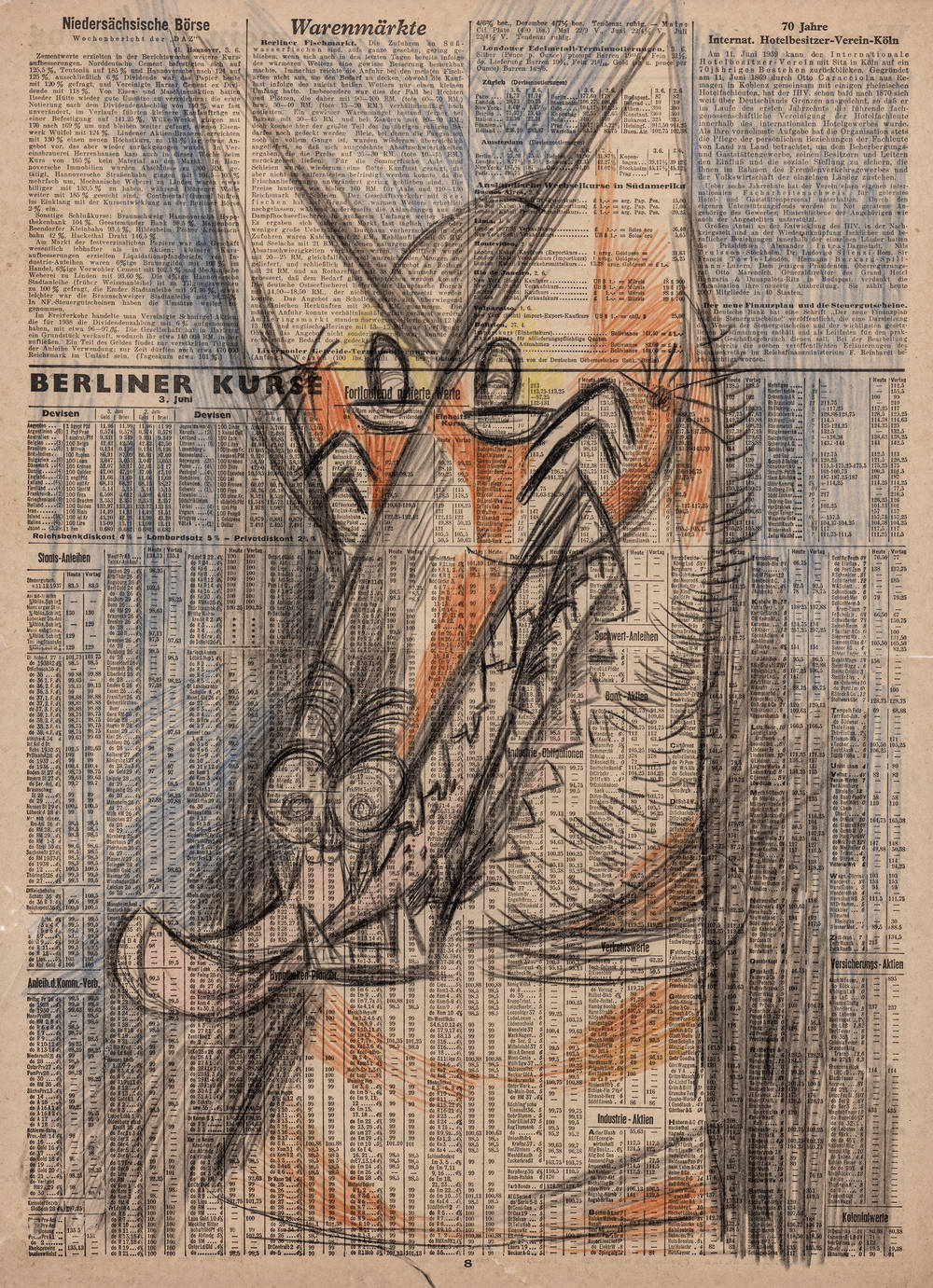

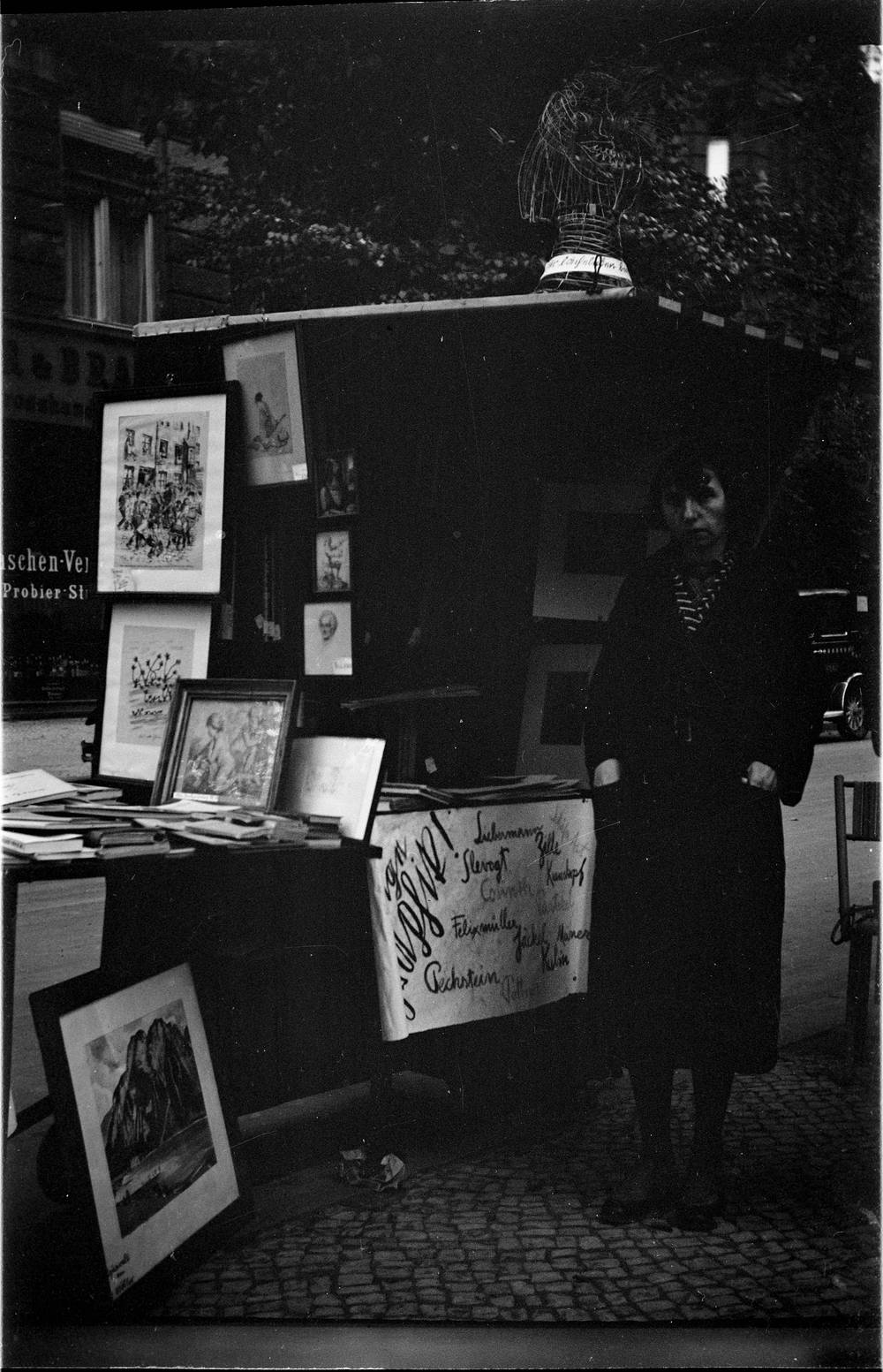

Even before 1933, from their elevated position Jeanne and Mimi bore witness to racist and politically motivated persecutions, which played out particularly dramatically on one of Berlin’s main streets. Orders started to dwindle and so Jeanne along with her friend Hans Uhlmann (1900–1975) and his mobile book-and-art stand moved up and down the Ku'Damm to earn some money, until Uhlmann was caught taking part in a leaflet campaign and imprisoned. The book trolley became a shelf, the studio a cage in which she was able to take refuge, but whose bars always harbored the risk of being discovered from the outside.

Mimi could no longer take the political pressure and in 1937 emigrated with her partner to Tehran, which was then a place of refuge for queer people. The majority of Jeanne’s friends also fled abroad. So what motivated her to stay during these years? Did she stay put because of feelings for her home city and for Hans Uhlmann, whom she visited multiple times in prison before he was released in 1935? Or did Picasso’s stirring painting “Guernica”, which she saw in Paris in 1937, affect her emotions and thus also her decision?

One thing is clear: Jeanne Mammen stayed put, sat plum in the middle of things, and yet had to become invisible at the same time. The anonymity of the big city appears to have provided protection in this case. Her art, which was influenced by Picasso’s style, was deemed degenerate art; the exhibition of the same name took place that same year. Yet far from being shocked into inaction or suffering a creativity crisis, she seems to have been gripped by a true creative mania. Her studio was now crammed with paintings, drawings, sculptures, and banned books.

When war broke out in 1939, Jeanne was appointed fire warden for her building and had to monitor the attic of the house under the constant threat that someone would enter her studio and see her artwork in the event of a bombing. She was not able to make a living through commercial art the way she had before without coming to some kind of arrangement with the Nazis (her commissioning publishers had been expropriated), so she worked as a craftsperson painting doll heads. Friends attempted to sell her paintings abroad, but her means remained meager. Could someone like this live on art alone? One almost wants to believe it.

It’s all the more important to look closely at these works and appreciate them, since they were created out of the purest conviction and in profound financial need. We know that male artists during the First World War transformed events at the front into art, and undoubtedly we can attribute the wealth of works by a female artist on the home front to a similar coping process.

Once the war and the permanent fear of discovery were finally over, Mammen set up her studio as an art salon. After those years of isolation in her cage, she sought company (fig. 5), and as the grande dame she welcomed primarily younger artists, theater people with whom she founded the political cabaret “Die Badewanne”, and literary figures, among others.

She acquired more and more curios; the online collection of the Berlin Stadtmuseum offers an impressive insight into this abundance. Just short of 840 items are listed there and they include, for example, a little monkey puppet, two wooden baroque angels, magic adder stones, sacred figures, ashtrays, dice cups, and a kind of fake orange made of glass in an orange net. In the two crammed rooms, years were spent blotting out the shadows of the past, sizzling, drinking, and smoking one cigarette after another around two provisional hotplates. The studio was filled with the joie de vivre of the next generation of bohemian Berlin.

Due to the age difference, the artist’s friends were able to preserve the studio for some years after Jeanne’s death in the form of the Jeanne Mammen Society, until it they too had advanced in age and it was taken over by the Berlin Stadtmuseum.

The kinds of effects the post-war reveling had on the paintings with their delicate surfaces and on the acidic paper of the prints are now being examined by restorers. Even today, there’s a somewhat tangy smell as you enter the two rooms through the tiny hallway. It’s a shame that this factor cannot be incorporated into the 3D tour of the rooms that the Stadtmuseum has posted online. After all, it is the (blue) haze of history that really makes Mammen’s self-proclaimed “magic den” so captivating – all the more so when you leave the studio and enter one of the slick-&-clean, perfumed concept stores nearby.