After the Iranian Revolution a nationwide dance ban was issued. It was subverted by smuggled video cassettes of dancer-in-exile Mohammad Khordadian, questioning traditional gender roles.

“Have you seen the new Khordadian video? It’s amazing!” – Both after the Iranian revolution in 1979 and during the Iran-Iraq War (1980–1988), just about every family in Iran was talking about dancer Mohammad Khordadian and his notorious music videos.

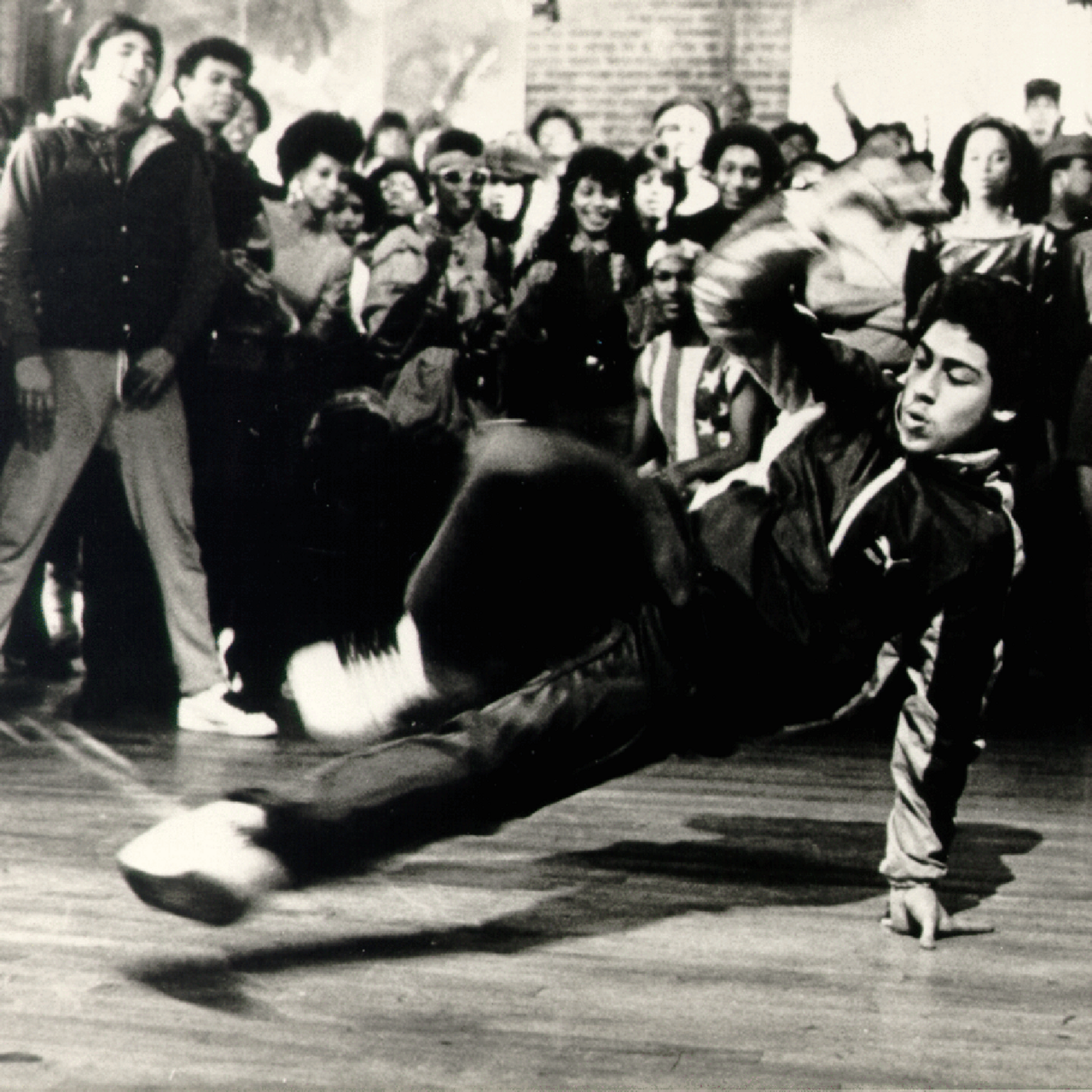

At the time, Iranian society was going through a severe depression because of the ongoing political repressions, the devastation caused by the War, and the increasing sanctions. When sociocultural restrictions, which took the form of strict censorship, were at their most severe, video cassettes (VHS) of dancing classes and performances were smuggled out of the United States to Iran, copied and passed around from family to family. In many cases, these recordings were the only available points of reference in order to learn “Iranian” dance.

Khordadian’s videos were passed around from family to family

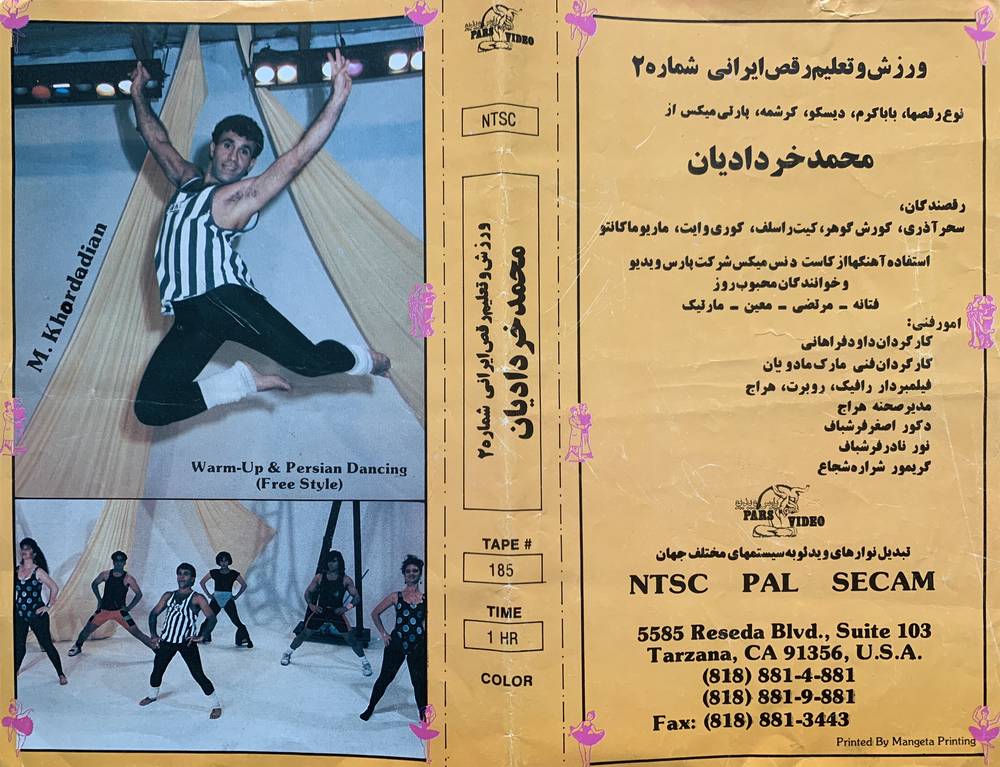

These video recordings made Mohammad Khordadian famous. After the revolution of 1979 and the subsequent ban on dancing, Khordadian left Iran, emigrating initially to the UK and subsequently to the United States. In Los Angeles, the largest diaspora of Iranians, by weaving together different kinds of dance such as folklore, the traditional Iranian dance known as “Baba Karam”, cabaret dancing, belly dancing and aerobics, he succeeded in anchoring his own individual style, which is often perceived as the standard “Iranian” dance.

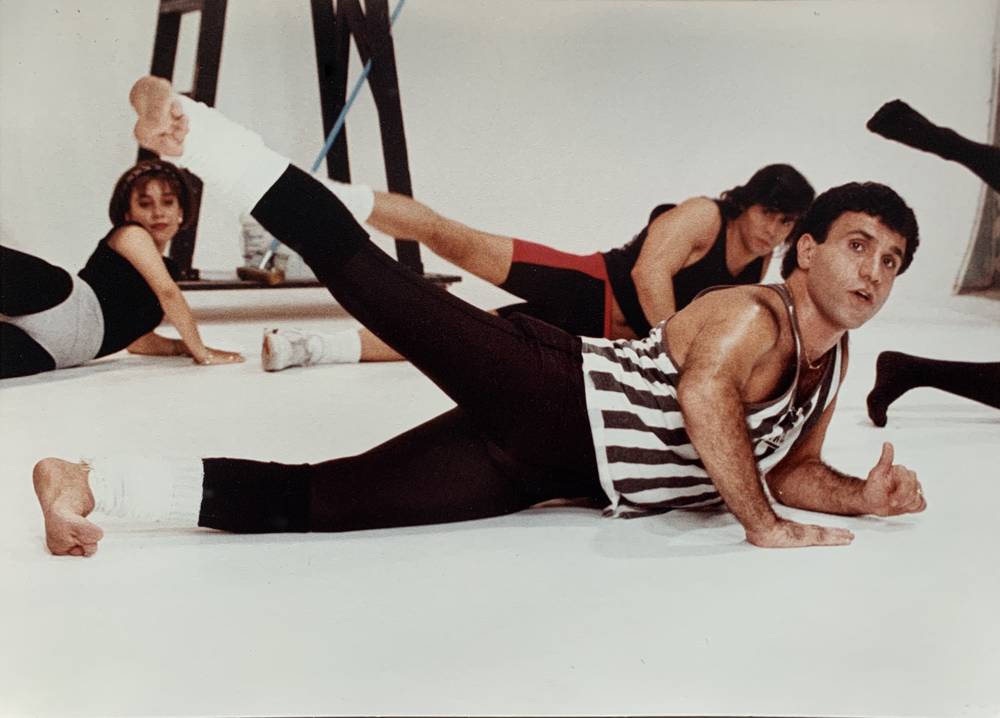

In a video work that they have designed for the exhibition at the Schirn, Ramin Haerizadeh, Rokni Haerizadeh and Hesam Rahmanian take the Khordadian dance style as their subject matter. “Dance after the revolution, from Tehran to L. A., and back” is a combination of video material and found footage which the three artists have been archiving since 2013. In their work, the artists document the training method which Khordadian uses in an effort to communicate his personal style to the viewer.

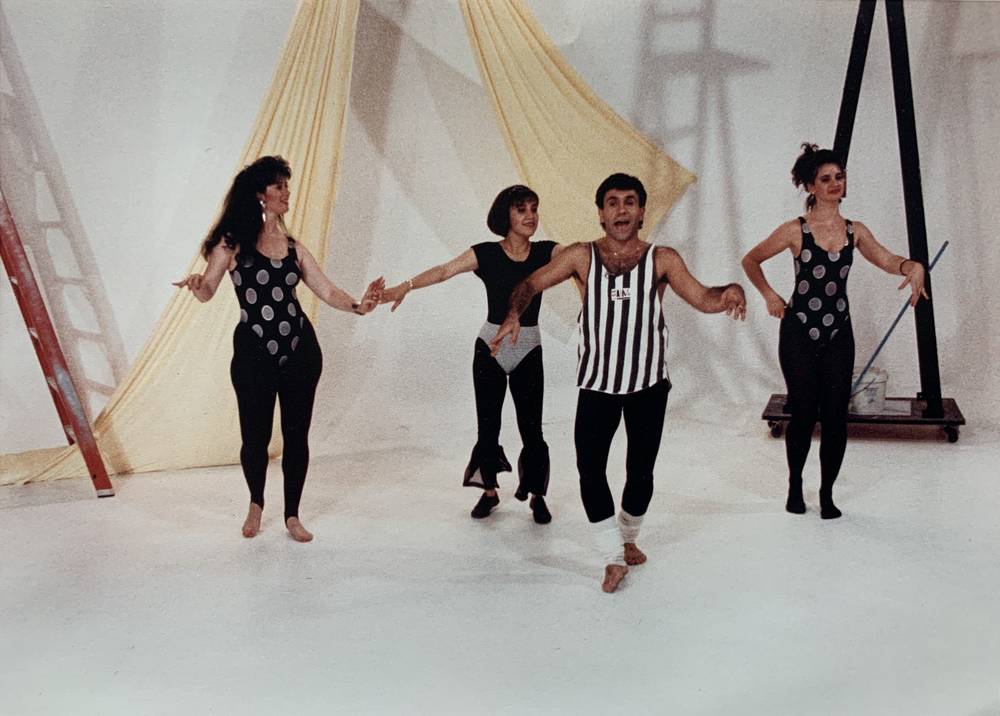

To this end he invents stories so as to be able to better commit the movements to memory and understand them, adding a touch of humor and exaggeration to them. He incorporates the coquetry and the movements to be found in the dance classically performed by women into the dances executed by men, for example playing with their hair, gentle, flowing movements of their hands, arms and heads, circular movements of their hips and their waists. For men, these kinds of movement were not originally intended as dances but as a kind of humorous diversion. However, over the course of time, thanks to Khordadian’s videos, flirting and feminine movements also became established and socially acceptable in “men’s dance”.

The freedom of movement and simultaneous absence of an institutional structure in Khordadian’s dance compositions allowed the gender roles in dance to become blurred. Suddenly, queer men in Iran could dance like women without being mocked or bullied by society – and without dismissing their dance style as merely humorous.

He changed queer Iranian culture

In their video work, Haerizadeh, Haerizadeh and Rahmanian specifically underscore the influence exerted by Khordadian’s dance style on Iranian queer culture and the joy he communicates through his dance. The focus is on the physicality of a contemporary dancer from the Middle East. It is a body perceived as “foreign”, one which oscillates between male and female. The highlights of the work consist of sections of found footage from the Web in which people are dancing alone, in pairs or in groups in accordance with Khordadian’s instructions, thus bracing themselves against the political censorship of dance and its gender connotations.

Dance is a basic element of Iranian cultural identity, one whose restriction, as is so often the case with prohibitions, produces the opposite effect. It makes what is being banned even more popular. Today’s younger generation also demonstrates a personal connection with Khordadian’s dance and they practice it themselves in places where they are particularly in danger – with videos trending on social media showing pupils dancing secretly in their classes, groups of soldiers on duty or even, particularly this year, nurses and doctors in full protective equipment in Iranian hospitals, performing their dances to create a better mood and to relieve stress at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Khordadian came out on a TV show in 2006 and in this way in the space of only a few years, succeeded in assuming a prominent place in Iran’s homophobic society and winning over people of all ages and from all social backgrounds – men, women, queer people as well as the religious and non-religious and Iranian living in the diaspora. With his humorous, individual fusion dance Khordadian encourages Iranians to emancipate themselves physically. In his dance, they can move around free of discipline and strict rules, communicating their joy to their fellow dancers and audience on social media. A joy that gives many people in Iran new hope in a situation devoid of perspectives.

UPDATE

The SCHIRN will be closed from November 2 to 30. We’ll be there for you online – with exciting articles on SCHIRN MAG and lots of content on Facebook, Instagram & Co.