At the annual digital festival Transmediale at Berlin’s Haus der Kulturen der Welt, discussions focus on the art and society of tomorrow – with the occasional nostalgic reminiscence.

When something is new, first of all a word has to be invented for it. And this word frequently serves as a metaphor – an image that enables us to understand the innovation, for example: The Internet was initially construed as a globally connected network of computers, almost like a spider’s web. Hence the term “World-Wide Web”. Other metaphors seem a little dated after a few years, such as “data highway” or “cyberspace”. Others adapt to new technologies, like the image of “the cloud”.

The cloud allows us to understand how our data are available to view from any location – because they are distributed decentrally and, in any case, are still immaterial somehow. After a while, we forget that we’re even using metaphors. The original meaning recedes into the background, like the image minted on a coin once it has been in circulation for a while.

Old romanticism and heightened contradictions

This year’s Transmediale was the festival’s 31st edition and took place from January 31 to February 4. The festival in the Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin focused on the Internet, or more precisely, the fact that the Internet as we know it was not always so. Everyone knows, of course, that there was a time before the digital hegemonic powers of Google and Facebook, but hardly anyone can remember that murky prehistory of global interconnectivity. A little bit of this romanticism is nevertheless inherent in this festival. It’s about art, about images, about the politics of identity on the Internet, it’s about cryptocurrency, about memes and about everything that generates injustice in the Web.

The motto of this year’s Transmediale is “Face Value”. This refers to the nominal value of a coin. “To take something at face value” means to accept something as it seems from its initial or outward appearance. The digital festival began with a “rally”, a political gathering, at which the participants give generally irate, five-minute presentations about what is wrong with and on the Internet. At the same time, one could also sense the disappointment people feel, for example when British culture critic Nina Power asked: „Why do we still have to work for eight hours a day with people we wouldn’t even speak to at a party? Why have we not long since moved on to a ‘post-work society’?”

The erstwhile utopias of the free Web have failed, she suggested, and instead of bringing liberation, the Internet has quickly transformed into a space where the contradictions of the analog world are heightened: race, class, gender.

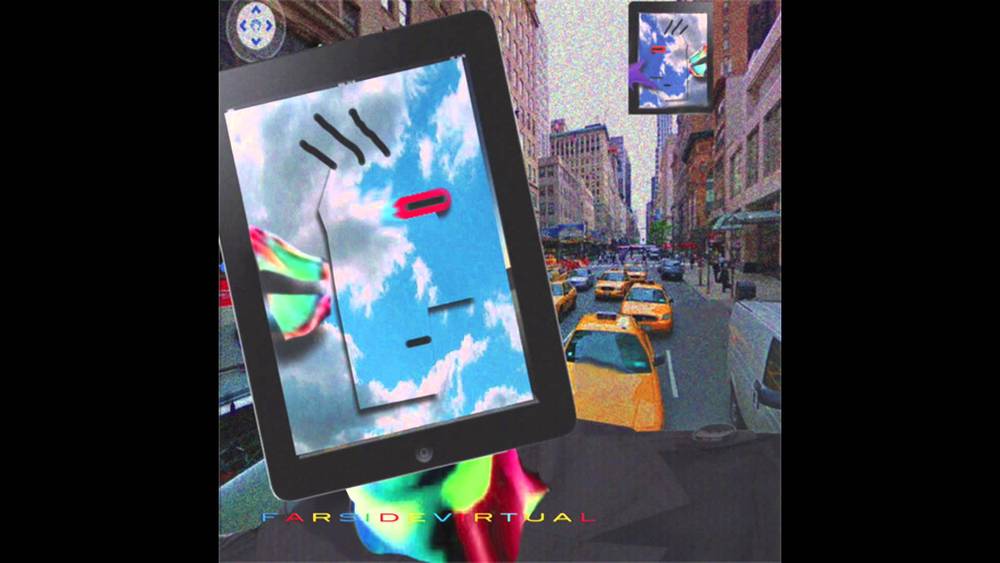

Yesterday’s Post-Internet art

Now the Transmediale is not only a festival for future forecasts and political demands, but also for digital culture. Certainly, terms like post-Internet or Vaporwave apply only to a limited extent, to make precise statements about works of art. The latter was a hype that began around 2011 and quickly spread: Electronic music from samples of elevator music and Italo-disco. Gradually the melancholic sounds drifted by Soundcloud, YouTube and into progressive art galleries, but ultimately, Vaporwave migrated into the archive of sunken pop trends.

New metaphors

A veteran of this movement is James Ferraro, who is probably the clearest sign that Post-Internet art is entering its Baroque phase. At the Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Ferraro staged a kind of opera for the Transmediale, entitled “Plague”. The aesthetic template for this is supplied by Bertolt Brecht and his break with illusionistic theater. An actor appears as an undead Steve Jobs, no longer able to control the spirits he called upon. There is a choir and music. On a triptych of three screens, a rendered film is shown: It all begins with a root, looking a little bit like ginger root. It grows and links up. And the viewers learn a new metaphor for the internet. The neuronal network or, more precisely, the self-learning artificial intelligence.

Why, asks artist Zach Blas on the third day of the festival, is the Internet presented as a globe? He knows the answer: because it is totalized. Because digitization has long since encroached on all areas of life, and it actually no longer makes sense to talk about the Internet as such. Indeed there is nothing left that is not linked up to it.

Eric Schmidt heads up Google’s parent company Alphabet. Google is one of the great colonizers of this globalized Internet – but he’s right when he says: “The Internet will disappear”. But not into thin air. It will disappear into the devices until every object has an IP address, until we no longer even perceive it – the idea of the Internet of things is born. The cloud is not immaterial, but rather has real political and social impacts. The metaphors may change, but the Internet has long since ceased to be distinguishable from reality.

You Get the Picture: On Movement and Substitution in the Work of Lena Henke

The artist LENA HENKE already exhibited in the SCHIRN Rotunda in 2017. What are the secrets of her practice and where can you find her art today?

'Have yourself an experimental Christmas'

Bored of watching the same old Christmas films over and over again? Here are some of our favourite experimental films for the festive season.

MOTHER IS MOTHERING. Lesbian motherhood in art

The role of the mother is often described, but most representations are still based on a heteronormative and patriarchal understanding. What does...

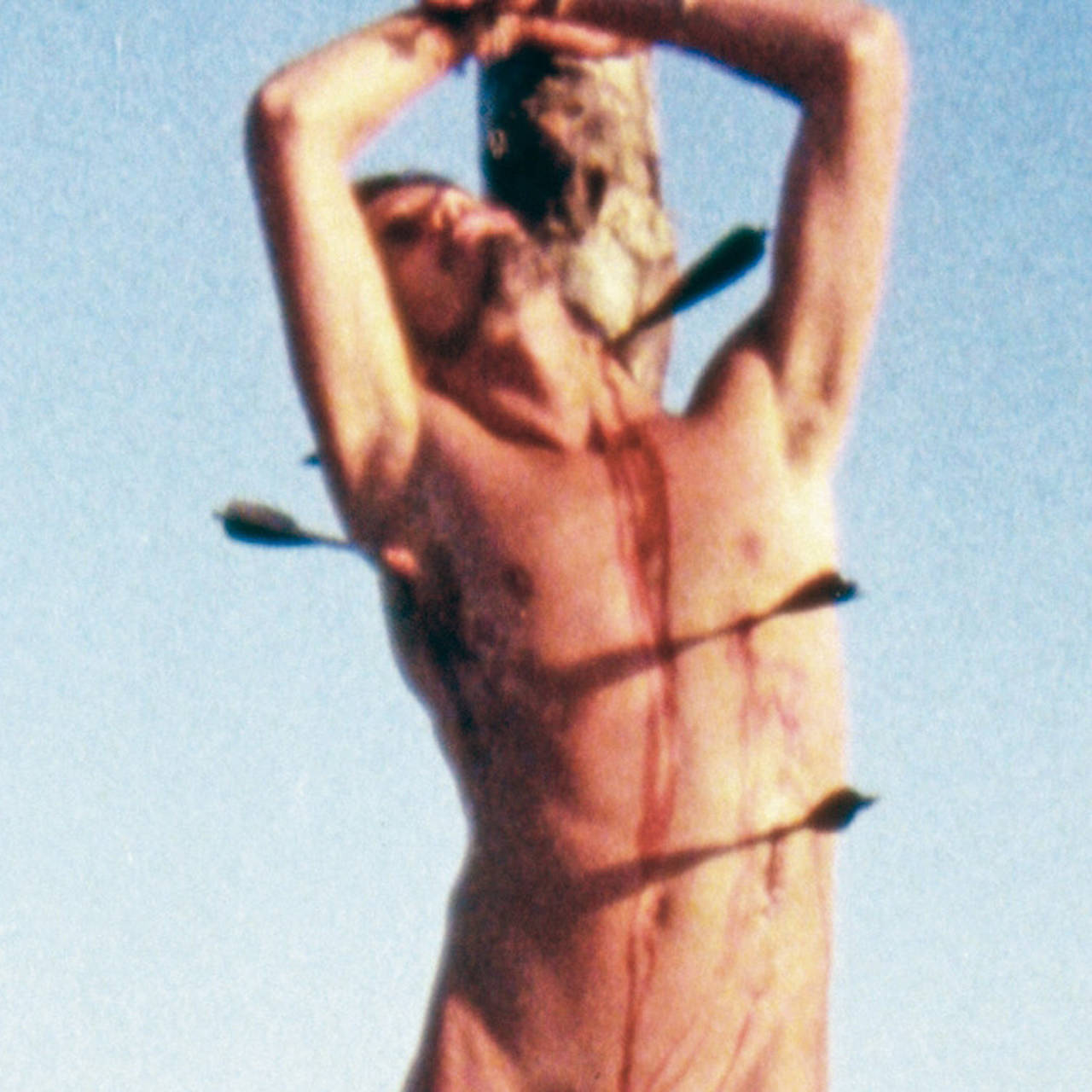

Queercoding in Art and Film: The Portrayal of St. Sebastian

While the sexualised portrayal of Saint Sebastian in Derek Jarman's feature film debut "Sebastiane" initially sparked social controversy in 1976,...

Clubs in crisis: What is the future for club culture?

Great things happen in crises, so they say. But maybe something is getting irretrievably lost. Clubs are not only places to celebrate, but also...

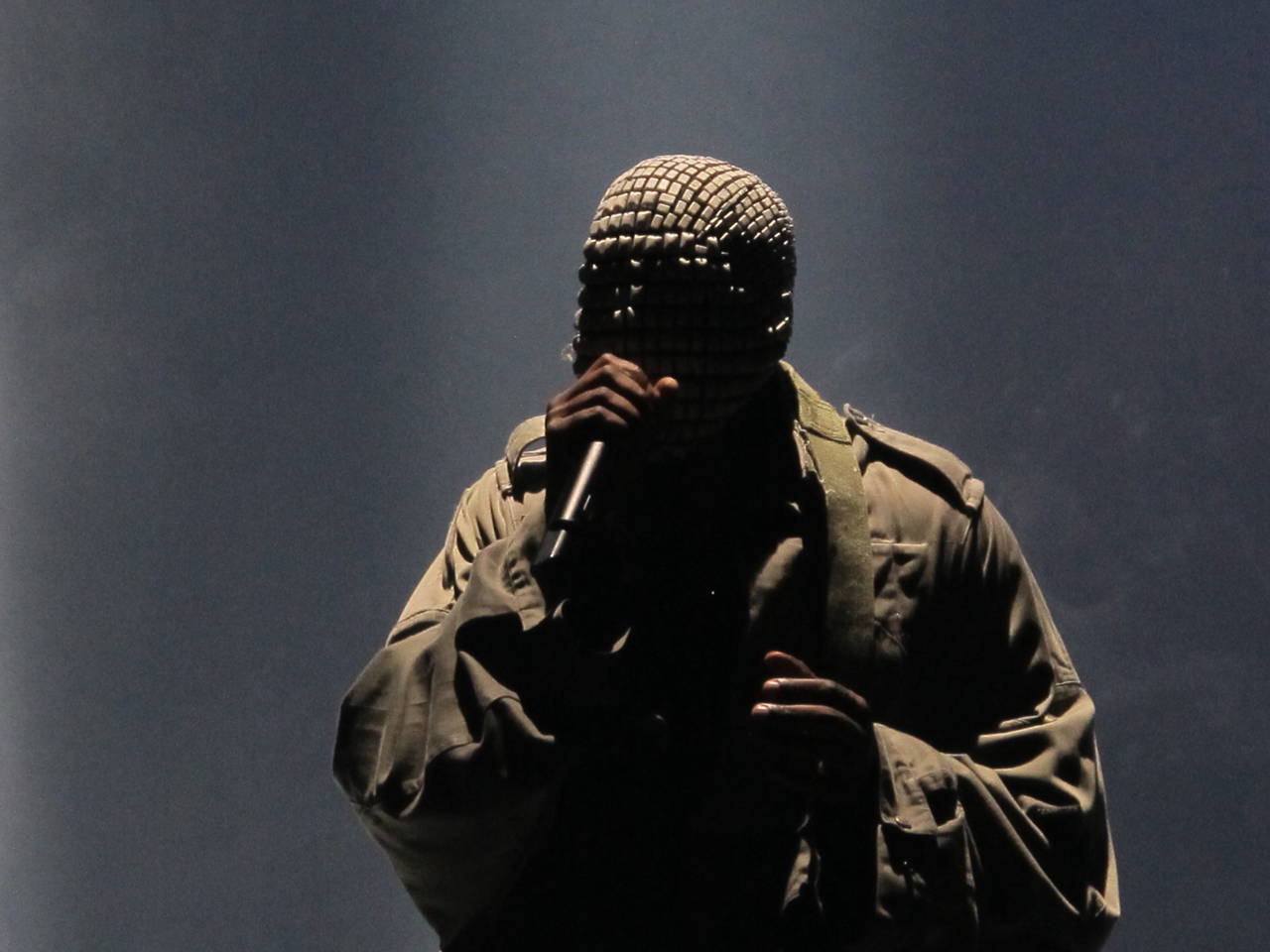

The New Normal: A Cultural History of Masks

Masked faces in public have become the new normal these days. A glance at art history and pop culture shows how masks reveal more than you might...

The quiet architect

Mark Noonan’s documentary film presents a portrait of the renowned architect Kevin Roche. His oeuvre includes some impressive museum buildings.

Best of Berlinale 2018

Outstanding cinematographic art across the sections: The SCHIRN MAG presents a selection of feature films, experimental movies and documentaries of...

Larger than Life

Often figurative and in extravagant dimensions: The feature film “A Private Portrait” is an homage to the painter and filmmaker Julian Schnabel that...